In the Sámara community center, Lucia Mahlich picks up the microphone, looks at her colleagues and shares a complicit smile. Two years ago she and her group “Project Coral” started working on rebuilding coral reefs along the Nicoya coast.

Today, Mahlich and 10 members of the project are going to tell 40 people about the advances and results they have seen since 2017. In 2017, the National Learning Institute (INA) graduated 22 people in coral gardening, a relatively new technique that started to develop in the country four years ago.

The technique Mahlich and her 21 colleagues learned seeks to “grow” corals in artificial structures under the sea in order to transplant them into natural structures when they are big. It’s a practice that is being implemented in three places in the country, Golfo Dulce, Quepos and Sámara. Only Sámara involves the community as part of the science.

Reaching this point hasn’t been easy for the group and that’s why it is so significant that today, August 8, they can share the results of something that they have worked so hard for. At the beginning very few things went right. They lost part of their work and even dealt with opponents to their initiative, like a group of fishermen that thought the project would affect them.

Community residents, Nicoya city officials and members of the Sámara water association, Red Cross and INA attended the meeting. There are also fishermen who now understand that they also need to conserve coral.

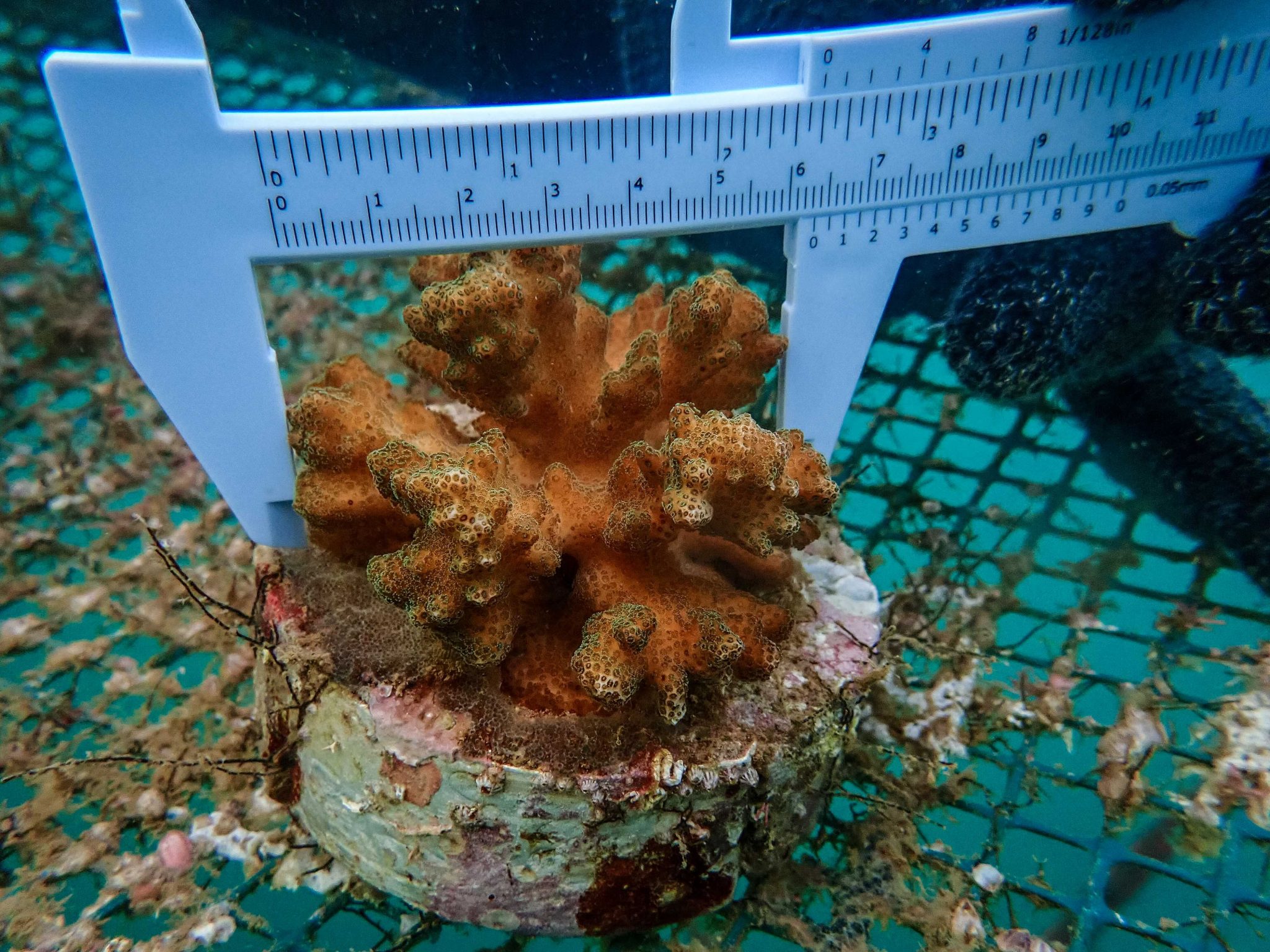

While they have suffered losses, members of the project have plated 200 pieces of coral. Photo: Project Coral

Endangered Coral

In order to start the presentation, Lucia Mahlich shows a series of Google Earth images where you can see urban development in Samara. The growth has provoked sedimentation in rivers that has damaged corals.

What I want to point out with these images is that the change in land use in Samara has affected natural resources. Corals have been affected by this situation,” she said.

The corals are part of reefs that are popularly known as “the jungle of the sea” because they are home to 25% of marine life. Fish, sponges and mollusks live there. They are diverse structures with different shapes and colors and are useful for activities like snorkeling and diving. They also attract fish and benefit small scale fishing.

But their actual state in the world isn’t good. A fifth of the world’s coral is dying. Other estimates indicate that the loss could be as much as 50%. The same thing is happening in Costa Rica, which is why President Carlos Alvarado signed a decree to protect and restore marine coral on June 8.

Other factors that affect coral are anchors dropped by boats, plastic, agrochemicals and even solar protectors.

This is the only project in Guanacaste, but it will take off soon in Culebra Bay and Papagayo in conjunction with the National System of Conservation Areas (Sinac), which oversees the project, according to Tempisque Conservation Director Mauricio Méndez.

Enthused about this project and the next one in Culebra Bay, Méndez said that replicating these initiatives is an excellent idea for recovering coral.

It’s good for a hotel, like in Matapalo, or Hotel RIU to take on the scientifici part.”

What has been done to restore them?

Two years ago, while they were taking a course at INA, the group built a platform for raising corals. In order to make the grow, they collect pieces of coral that they find at sea because they break off naturally. If they can’t find any, they cut small pieces of living coral. Then they super glue them to the artificial structure, which can be a platform (like a bed) or an antenna.

When the artificial structures grow, it’s easier to be sure that they will receive enough light, that they won’t be harmed by sedimentation and that fish don’t feed on them too much like they do on natural structures, according to INA diving instructor Cristian Gómez.

They are then planted and the group visits the site every 15 days to remove things that get stuck to them and slow their growth.

We clean off the algae, barnacles, which competes with coral, and the sediments that come from rivers,” Martin Richard Paradis tells the group of 40.

Martin later explains that the coral without care would take 15 years to reach adult size, while it can be done in five years with proper attention and cleaning.

Is this work enough to recover them?

At the start, the group’s focus was planting coral, taking care of them and recording their growth, but through time, they realized that sedimentation and other factors can harm the coral they planted.

“In order to have a positive impact in the bay, it’s not enough to just work in the water. We have to work outside it too,” Martin says.

That’s why they have developed parallel activities to raise awareness in the community. For example they held presentations with children and teenagers to teach them about taking care of natural resources. They planted 450 trees along the Malanoche river in Samara and they built nine structures where boats can dock without using an anchor.

Once every 15 days, members go out to see to clean the artificial structures. Photo: Project Coral

So, are we recovering coral?

Until today, the group trained by INA has planted 200 pieces of coral in the artificial structures, said Carlos Pérez, project researcher.

“It hasn’t been fast. Mortality rates were about 70%. As we advanced, we have improved techniques and we reduced the mortality rate to 40%,” he said.

The group has transplanted 48 of the 200 corals to natural structures and they continue to monitor their growth. According to Pérez, coral grows faster in Sámara than in Golfo Dulce.

Their eyes light up when they talk about the advances they have had through the years.

“It’s all been by trial and error. At the beginning we couldn’t get them to grow, they fell off the platform and would end up on the beach. We didn’t know what was going on. They would die often or get covered in algae. Then we started making adjustments and we began to see results.

Pérez and his boss Marco Acosta see beyond just restoring coral. They believe that this is a big opportunity for Sámara to promote the tourism and fishing industries.

We are going to increase biodiversity and we all win by doing that, water quality, tourism, development, fishing,” Pérez says.

Acosta adds that in Sámara they found a community willing to donate money toward the purchase of material and excursions out to sea. That encouraged INA to work here.

For Mahlich and Martin, that has been a challenge. They work ad-honorem and with the materials that they buy with money they collect from donations. One of the members provides the boats and the diving equipment for expeditions. “We have a pending debt,” Mahlich says, referring to the resources that Martin has invested in fuel and diving equipment.

The debt is heavy. But their biggest concern is that the coral may disappear and that’s why they don’t stop working. “We are going to recover the coral reefs to the level that Sámara had 40-50 years ago,” Pérez says without hesitation.

Comments