Just a few meters from doña Ana Esquivel’s house in Barrio El Cacao de Río Seco, in Santa Cruz, there’s a hole in the earth filled with all kinds of trash. Every time it stops raining, and in summertime, the mountain of garbage goes up in flames, spreading ashes and thick smoke across nearby ranches and homes.

Next to the hole lies a bag full of diapers, which don’t easily burn, and near that, two barrels filled with glass bottles that are of no use to doña Ana, but which she can’t burn or bury. Along the Nandamojo River, which flows by her home, you can find anything from bottles to the remnants of washing machines and other discarded appliances.

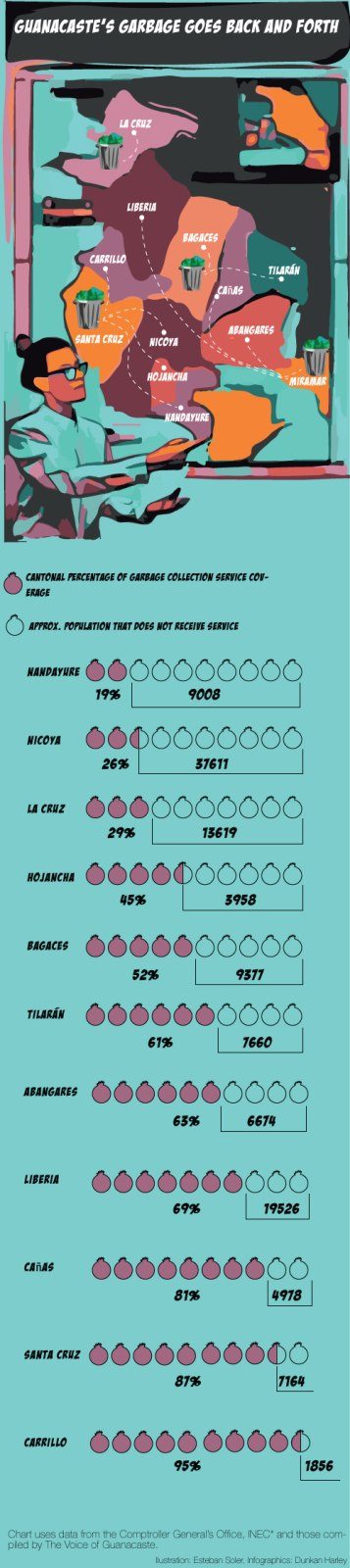

Doña Ana is one of nearly 122,000 people in Guanacaste who are abandoned by waste management planning by the province’s 11 municipalities, as none of them provide garbage collection for 100 percent of the population.

This is despite a law requiring them to do so, the availability of financing from the Institute for Municipal Development (IFAM), and the existence of several options to reduce the amount of garbage and improve service coverage.

Only Carrillo is close to meeting those requirements, with 95 percent coverage. At the other extreme are La Cruz, Nandayure and Nicoya, where waste disposal services cover less than half of the territory, according to a Solid Waste Collection Operative Audit by the Comptroller General’s Office published in early 2016.

The Voice of Guanacaste verified these details in a joint investigation in September and October with Punto y Aparte, an exchange program with journalism students across the country.

Municipal Requirement

According to Law N° 8839 for Integral Waste Management, municipalities are responsible for efficient and periodical garbage collection for all residents.

Mayors interviewed for this story blamed budget limitations that prevent them from reaching isolated communities. However, IFAM has loans available for that purpose.

“IFAM can finance the purchasing of equipment or construction of a transfer center, in addition to Technical Assistance, which refers to infrastructure design,” IFAM stated in an email.

Officials at that institution understand that garbage collection in isolated communities and with few residents increases costs, but their proposal includes creating transfer centers for residents to drop off garbage for a municipality to process it, an option that municipalities still haven’t taken advantage of.

“Our credit conditions are very generous, and in little time, at low interest and with attractive terms, we can design and generate an efficient solution for the Municipality,” IFAM’s press spokesperson added.

Faced with this situation, the nearly 90,000 residents are obligated to look for other options. In most cases, those options are unsustainable, such as what doña Ana resorts to with no other choice.

Roots of the Problem

In the eastern part of the province, in San Rafael de Abangares, Alejandro García and his wife, Marta Villalobos, also have no garbage collection service. They say the municipality began collecting garbage in the neighborhood a year ago, but workers don’t come to their house or their neighbors’ homes because the road is in bad shape. Alejandro complains that there are no plans to fix it, either.

As in this case, roadway conditions are one of the main reasons municipalities cite for not offering garbage collection services. Mayors also mention limited budgets, insufficient equipment or equipment in bad shape, and in some cases, citizens who refuse to pay waste management fees.

One example is Cañas, where Mayor Luis Mendoza said the municipality is in the process of providing access to Lajas and Porozal sectors, but problems exist with local residents.

“To be able to enter those communities we need the consent of all residents, because we charge for the service, and there are some communities that want the service but aren’t willing to pay,” Mendoza said.

In Hojancha, Mayor Eduardo Pineda said a few splits in the road are all that are lacking to reach Socorro and Cuesta Rojas, as well as Matambú, which because it is an indigenous reserve requires several consultations, toward which the municipality says it is working.

La Cruz and Liberia blamed the problem on equipment. Currently, los cruceños have a garbage truck that’s no longer usable.

Bagaces also has equipment problems, with only one garbage truck for the entire canton.

The money each municipality invests annually in garbage collection depends on several factors. The amount varies depending on budgets, population and territory.

For example, Cañas invests ¢11 million annually, while Hojancha invests approximately ¢52 million. Nicoya spends about ¢240 million annually, and Liberia, ¢350 million.

Informal Dumps and Bad Waste Management

A lack of coverage for collection isn’t the only problem for Guanacaste residents. Poor waste management also harms the environment and can damage the health of locals.

Currently, the province has two informal dumps in La Cruz and Bagaces, and a landfill in Santa Cruz. Other dumps have been shut down, such as Tilarán in 2012 and Cañas in 2016.

Eugenio Androbeto, of the Health Ministry’s Office of Human Environmental Protection, says that garbage is left in the dumps without any type of treatment. It’s simply stacked up, generating a proliferation of flies, vultures and foul odors.

He said garbage creates conditions that foster the spread of diseases transmitted by mosquitoes, such as Zika, dengue and chikungunya. It also causes rat and fly infestations, which also transmit diseases.

Liquid byproducts of waste decomposition, called percolados in Spanish (or leachate, in English), contaminate soil, pollute rivers and produce methane gas that contributes to climate change. It’s more damanging than carbon dioxide.

Why Isn’t the Problem Solved?

If resources, technology and financing already exist, why hasn’t a solution been adopted for garbage collection?

According to Juan José Lao, an attorney, doctorate in environmental economy and founder of the companies WPP Coriclean and Non-traditional Environmental Waste Solutions, the problem stems from a lack of political will and disobedience and impunity in front of the law.

The Law for Integral Waste Management dictates that municipalities should work to close informal garbage dumps in their regions, although a specific term to do so isn’t stipulated. According to Lao, the municipalities’ duty is to adequately dispose of waste, as well as provide recovery centers with special emphasis on small and medium scales for recycling later.

In 2012, the municipalities of Cañas, Bagaces and Tilarán signed a contract with Bioenergía Tica S.A., a company that specializes in producing energy from waste. The contract sought sustainable waste management by converting garbage into dry fuel.

Although that contract stipulated the project would begin within six months of the contract’s signing, five years no progress has been made.

Company director Carlos Graffigna said they are conducting a second environmental impact assessment (EIA) after the National Technical Secretariat of the Environment Ministry (SETENA) shelved the first. Graffigna expressed his disapproval that SETENA took nearly two years to review the first assessment before shelving it without offering the opportunity for revision.

An Environment Ministry document describing that decision, made along with SETENA, notes that the first EIA contained “numerous and significant technical deficiencies that failed to comply with SETENA’s norms.”

“The project committed to pay the three municipalities 5 percent of net income to invest in better equipment and collection tools, as well as recycling programs and waste classification from its origin,” Graffigna said.

For specialist Lao, a solution requires each canton to work with other municipalities to establish integral solutions that have a regional scope. Solely expanding the territorial reach of waste management services won’t generate a significant change in environmental impact without creating sustainable methods of disposal.

Among possible solutions are the elimination of informal dumps, their replacement by waste treatment centers and utilization of waste to generate renewable energy.

Solutions, financing options and alternatives to reduce waste all exist, as do disposal methods that don’t pollute. Nevertheless, municipalities aren’t taking them into consideration. It remains up to citizens to demand accountability.

Comments