A breeze opens a metal gate and blows into a passageway that still smells of damp earth and bygone days. In the dim lighting, you can make out a series of golden sparkles in the half light, portents of fortune.

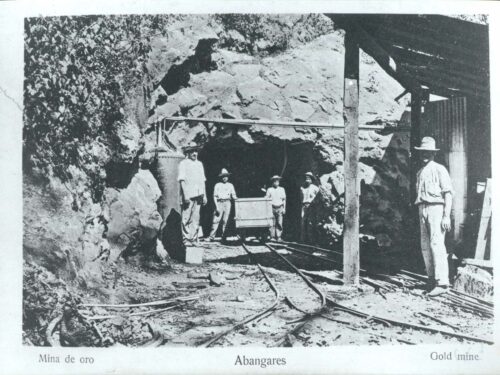

Going into one of the mines in Abangares is like being one of those adventurers who left behind friends and family to enter the bowels of the mountains and find the much coveted golden metal.

These thoughts captivate me while I look around the Boston Tunnel, known as one of the passageway tunnels in the Abangares Ecomuseum. Today, this passage is blocked with dirt, but about 100 years ago, it was one of the main mining shafts from which hundreds of tons of gold were removed.

It all started in the 1890s, when the mining industry was opened in the canton of Abangares. With it came foreign companies to exploit mineral resources in the area on a large scale.

“Hundreds of workers were mobilized in and out of the country to do the dirty and heavy extracting work. Most of them left their lives behind in the tunnels as a result of the preposterous exploitation to which they were subjected, as well as alternative respiratory disorders, skin and digestive diseases, in addition to [deaths] caused by accidents, venereal infections and alcoholism,” relates the book La Guerra del Oro (The Gold War) by Antonio Castillo Rodriguez.

The Ecomuseum

Founded in 1991, visitors to the Ecomuseum become a permanent part of Costa Rican mining history and the exuberant nature of the La Sierra district of Abangares.

From the moment we arrive, Victor Hugo Montoya, a local expert and guide, welcomes us warmly. And while I start to bombard him with questions, he warns me not to mix up the names of the locomotives.

“Because one time a journalist wrote that one of the trains was called Maria Cecilia and the correct name is Maria Cristina,” he warns me. The other train, known as La Tulita, is up the mountain so that visitors can see it and get an idea of what the daily grind was like for those “iron oxen.”

As we move forward through the forest, the ascent becomes pronounced. After 15 minutes that leave us almost out of breath, Montoya decides to tell a story about something that happened in the mines.

“Miners came here from all over the world, but mainly from Central America. Once it happened that they were stealing gold. Because of this, the foremen in charge, who were black, were ordered to check every one of the miners as they were going out of the mines and to make them undress. But one of them, on one occasion, didn’t want to take off his clothes because he was one of the ones responsible for blowing up the dynamite he had to be constantly in and out of the mine. Due to this, the foreman shot at the miner, which set off a massacre between miners and foremen that lasted for three days, known down to today as La Matanza de Los Negros (The Massacre of the Blacks),” relates Montaya.

After passing the gunpowder house, where the explosives were kept, we finish the tour in the mallets building, a structure that, in its time, was more than three stories high and housed 80 iron mallets that were used to crush half a ton of gold per month.

Montoya estimates that, at the current price of gold of 15,000 colones ($28.50) per gram, at the peak of the mine production, half a ton of gold was removed per month, which amounts to more than 8 billion colones ($15,240,000).

Mining work today is very different from back then, more than 100 years ago, when they penetrated into the veins of the Abangares mountains. The current mining work is regulated by the government, but injustice, exploitation and sacrifices continue, as if gnawing the entrails of the mountains were cursed.

Comments