Every January 14, Santa Cruz wakes up with a festive spirit. Bullfighters arrive with the mindset of enduring the horn of the best bull and the audience congregates with the expectation of enjoying one of the best and most traditional festivities in the country.

José Antonio “Chepillo” Viales Arrieta has worked for more than 30 years as a barredero – the name given to those who put together the bullring floor – in the National Typical Festivities.

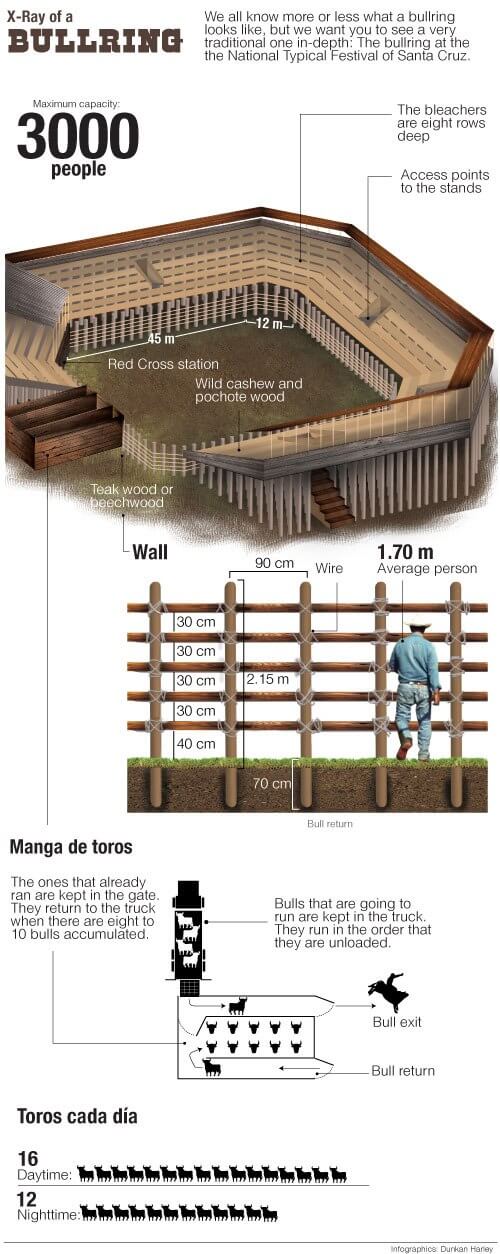

Assembling the ring floor is the first step to building the bullring since it gives the ring its circular shape. This space must have a diameter of no less than 30 meters, according to bullfighting regulations.

“Chepillo” knows his profession to perfection and can say without a doubt how many posts and nails are in the floor and if they are located in the right position.

“In total there are 126 posts in the floor. They are 70 centimeters deep and two meters and 10 centimeters tall,” he assuredly explains to me with his measuring tape in hand.

A common bullring is made up of stands, or bleachers, joined in one single structure. Each bleacher has the capacity for approximately 300 people.

Of course, not all bullrings are the same and they depend on the size of the event and the place where the festivities will be held, but the one in Santa Cruz is definitely a historic reference.

The Business of Bleachers

Once the floor has been put into place, the bleachers come next. The Bleacher Association of Santa Cruz (Asotasa) is in charge of them.

Asotasa was formed seven years ago with 10 sets of bleachers in order to guarantee work and income during festival season.

“We pay the Festival Commission ¢80 million ($143,000) for doing all the bleachers, then we charge the entry fee,” explains Alfredo Álvarez Delgado, who is in charge of coordinating 11 groups of workers that put these structures together at the Santa Cruz bullring.

So readers get an idea, if the association fills at least 10 bleachers for ¢5,000 ($8.90) per person, the association will make as much as ¢40 million ($71,000) in net earnings (¢120 million in revenue minus ¢80 million they pay the commission).

The wood used for the bleachers is wild cashew, teakwood and beachwood and Alvarez says the majority of it is donated by residents in the canton.

The activity is profitable precisely because they don’t have to invest in buying the majority of the raw material (the wood) and they reuse it in other festivities during the Guanacaste festival season.

According to Álvarez, 12 people work in in each group, so between those who assemble the floor and the bleachers there are more than 100 workers in the bullring with a wage of ¢1,200 ($2.14) colons per hour.

Tradition that Persists

The construction of the Santa Cruz bullring is like a ritual because of the years it has collected and because it is always done in the same place, the famous Plaza López or Los Mangos, in the city center.

The tradition is so strong that residents have disobeyed orders from the Health Ministry that sought to relocate the structure to another site due to the plaza’s poor conditions. In fact, in 2017 they had to transfer the tents to the El Paraje fairgrounds in

Diriá and the cultural and religious activities to the Bernabela Ramos park.

But the bullring stayed put, right where it was. After many disputes, the ministry allowed bullfights to continue to be held in Plaza López.

Also read: Plaza López: How Tradition Fought Security in Santa Cruz

“How are we not going to defend ourselves against this, if it’s been going on for 170 years just for the Health Ministry to come one day and take it somewhere else,” Chepillo affirms with conviction while he firmly holds a club.

Chepillo remembers the times when his uncle, Santa Cruz rancher Marcial Arrieta, used to bring 20 bulls of the same color everyday to the festivities.

“The parade of bulls used to reach the Plaza de Los Mangos,” he recalls nostalgically. “It was a unique spectacle.”

In 1965, they stopped holding the parade after one of the animals ended a musician’s life, writer Edgar Leal Arrieta says in his book De Fiesta en Fiesta en Guanacaste.

The custom of bullfighting isn’t lacking in controversy. It has provoked injuries and even deaths, but it’s full of passion because of the fervor it generates among those that attend the festivities. For better or worse, the tradition refuses to disappear in modern times.

Comments