It’s eight in the morning. The hot fried gallo pinto is ready in one of the many pans in the kitchen. Odetth takes a pitcher of hot water and pours it into the coffee filter sock. While the water turns into coffee little by little, she puts down the pitcher and continues shaping tortillas by hand.

Then she pours more water into the coffee sock, turns halfway around and takes two eggs that she cracks into a hot pan. She does everything at the same time, in a minute or so.

Her daughter will wake up in a little bit and ask her for breakfast with a cute, comical gesture, opening her mouth and pointing at it with her index finger. “Like a baby bird,” Odetth will say. The girl’s father doesn’t live with them, but he’ll show up later as he usually does and Odetth will serve him food.

She looks so focused that you would never guess that inside her head, a tennis match is going on with her thoughts bouncing back and forth between items on an endless to-do list that includes sitting down to study with her eight-year-old daughter, cooking, cleaning the house, paying off a debt, doing an assignment for a course she’s taking, starting a business, delivering the study guide sheets that her daughter’s classmates’ mothers will pick up…

I can’t die, Mamuchi. My daughter needs me. Imagine if I keeled over and my girl ends up alone. I want to leave her when she’s as old as Gretel, as Amando,” she says, referring to her older daughter and son, who are 31 and 25.

In Nicoya, where she lives, Odetth is known as “Tigra” (Tigress), synonymous with agile. She was given that nickname during the many years that she managed several bars and restaurants, and people found that she was very on top of things.

Someone might think that she’s so good at multitasking and has the ability to manage endless to-do lists in her head because she is a woman and a mother.

But in reality, Odetth says she learned that as a “baby” because girls are brought up already playing at the unmanageable juggling act of multi-tasking such as planning and doing housework, paying bills, looking after their job, studying, and keeping an eye on their children and their parents, who live nearby.

The workload has doubled because women’s achievements in the workplace have not gone hand in hand with equally dividing up housework. While society demands that women be good at everything, a large portion of men limit themselves to being good at their jobs and assume minimum co-responsibility for the home.

Marleny Campos, a psychologist and scholar from Guanacaste, explained it like this: “There is a demand to continue fulfilling the traditional roles of the home but to also fulfill the role of provider, whether or not she has a partner.”

That dynamic chains women to more working hours at home. In rural districts (which includes 47 of Guanacaste’s 59 districts), women dedicate up to 26 hours more than men to unpaid domestic work. In urban areas (the remaining 12 districts of the province), the difference is 20 hours, according to the latest survey on use of time by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC).

The excessive weight they carry on their shoulders leads to a series of emotional and mental strains. “A series of stress, depression and anxiety stem from it,” psychologist Campos indicated.

Odetth admits it. “There have been days when I want to run away, and I see my princess, Mariana, and my doll is so lovely, that she doesn’t need to see me down in the dumps,” she said in a slow and deeply serene voice.

Although it isn’t currently the case for Odetth, for women in other households, staying home means being shut in with a partner who beats them and mistreats them psychologically and mentally.

Odetth makes coffee at home in the kitchen, which also used to be a soda (a small restaurant) where she sold Guanacastecan dishes and fast food until a little over a year ago. The gallo pinto is ready, and in the same place where she has the pitcher, she is making homemade tortillas with corn that she ground herself the day before. Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

“Stay at Home” with Inequality

She is 51 years old and is proud of her Chorotega features and the Nahuatl words that she still uses in her daily speech. Her skin is chocolate-colored and her hair is an intense black. She speaks slowly, deliberately, as if searching for the exact words to express herself. She likes to call people “Mamuchi” (mumsy), “Mami” (mommy) and “mi amor” (my love). She also likes to show her affection through her cooking, by giving people the giant tortillas she makes by hand and sharing what she has been given with others.

To Odetth, sharing is the key to never lacking anything on the table. She tries to convince herself of that, even though she confesses her concerns all at once.

I don’t make money, so my hair falls out. I chew on my nails,” she admits.

A little more than a year ago, Odetth ran a small restaurant out of her house, but she closed it because the business license fees were burying her and because she and some friends from Nicoya dreamed up an idea together: La Mazorca, a future business with food that is 100% Guanacastecan that she is developing with a group of women.

Since closing the restaurant in her house, she continued making whatever dish people request: a hamburger, arroz con leche (rice pudding), tortillas, tamales, achiote chicken, ceviche… whatever. She had to do it to get by, but the pandemic started to empty people’s pockets, and hers as well, since they couldn’t afford to buy food from her.

Psychologist Marleny Campos affirmed that the need to continue putting food on the table increases the distress for women in the midst of the pandemic. “They have to continue fulfilling their work role and intensify the role of caring not only for their children, but also for their partner if they do virtual work or normal work,” she explained.

Also, women have historically assumed the role of caregiver for sick family members, even if they have COVID,” she added.

“And another thing that has aggravated it in this context is the situation with the educational system, as there is a great demand for spending time with the youngest sons and daughters.”

That is an extra responsibility that Odetth has had to take on. “At least they send me all the work. They don’t send me one thing. They send me all of it, all of everything, Mami,” says Odetth about the subjects that she should teach Mariana.

“It’s a lot and there are things that I don’t understand and I have to ask for help,” she said.

Help to help Mariana, which is urgent for her. What she usually doesn’t know is how to get psychological support that would give her a way to lighten the emotional, domestic and mental load.

“I need it, to find myself. Because there are moments when I feel like I’m not me, even though I have character,” affirmed Odetth. “I feel that I can look for help from INAMU (National Institute for Women), and how good it would be if they gave me a push. I would be the happiest woman in the world,” she said.

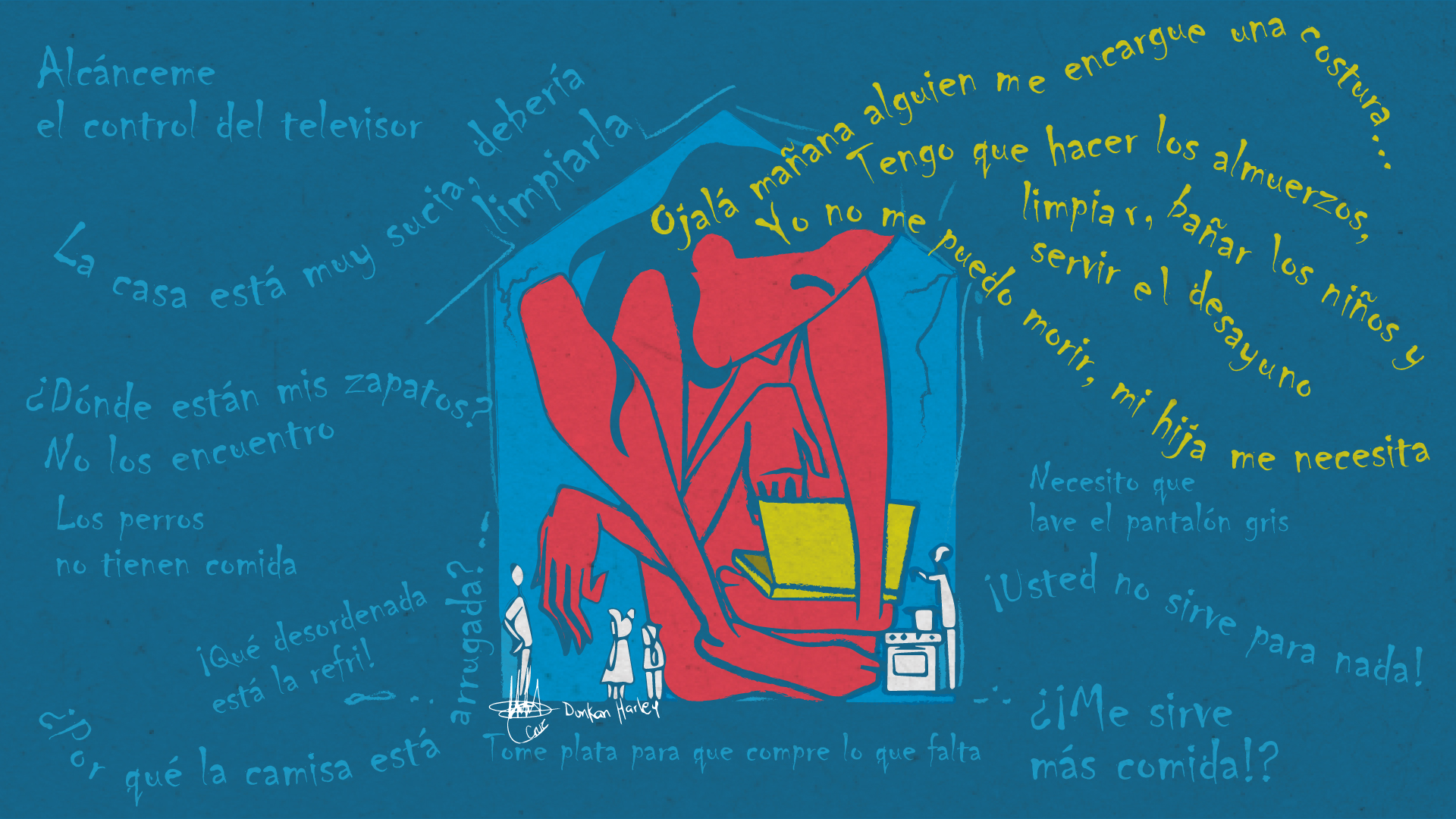

Illustration: Roberto Cruz

She isn’t the only one overwhelmed. Due to the pandemic, the Costa Rican College of Psychologists got a group of 200 volunteers together who, since May, have been responding to 911 and 1322 calls from people affected by mental health problems. As of October, seven out of 10 people receiving psychological assistance were women, mainly due to symptoms of anxiety and stress.

“What we women have fought for, for the State to assume responsibilities in education, health care and caregiving so that we can develop our potential as individuals and citizens, has been put back on us again in the pandemic,” indicated the former coordinator of INAMU’s gender violence department, Ana Hidalgo.

“This is an additional burden of discrimination that society is putting back on us and that makes us solely responsible for domestic labors,” she added.

This reality, like the one Odetth faces, in itself already destabilizes well-being. But as a survivor of domestic violence, she knows that at other times in her life, a pandemic like this would also have condemned her to live with abusive partners who left indelible marks on her memory and on her body.

The least safe place for millions of women in the world is their house, the United Nations (UN) determined in 2018. Their domestic partners and relatives are their main aggressors and potential murderers.

This is an experience that women of all ages live with, not just in relationships,” scholar Ana Hidalgo pointed out. She sums up that many women are trapped.

“They are trapped because they can’t get out, they have to take care of someone, they have to work in the house and provide care, or they are stuck with a violent partner with little chance of asking for help. They are also trapped by economic dependence, which is the historical trap for women, if they had economic autonomy and lost their jobs,” she explained.

In INAMU’s regional office in Liberia, which serves women in the province, they have noticed an increase in consultations with women for domestic violence. Between March and October, they have helped 468 women, 50 more than the same period last year.

Odetth, 51, and her daughter Mariana, 8, study in the morning. This is the routine every day since the pandemic forced her to become the girl’s teacher. When Odetth doesn’t understand something about the subject, she turns to a niece for help to explain it to Mariana. Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

Keep Building a Different World

“We had nice things. Not everything was hard. We had a river, we had corn to make pancakes and tortillas, jocotes (Spanish plums), mangoes, oranges. We had a marimba (percussion instrument) and my cousins played marimbas and we had such dances that I still have the zest inside of me, because in my family, there are marimba players, guitar players and singers.”

A family of performers, then.”

“Aha, Aha.”

“And what talent did you get?”

“Believe it or not, I have two guitars, but I never learned to play because I dedicated myself to work.”

Her work was the ladder that allowed her older daughter and son to stand on their own two feet, Odetth said. With that same formula, she’ll continue to guide Mariana, so that she can live an easier life than hers.

The girl, who constantly comes over to her and gives her kisses on the cheek, affirms that her mother is the best in the world. “She is very loving and when I do something wrong, she corrects me. She is the most special mom because even if we don’t have money, she always throws me a small party for my birthday,” she says as she looks at her with eyes gleaming with admiration.

And Odetth, who knows that her daughter constantly looks at her as her role model, doesn’t have time to do anything other than continue embroidering her world and Mariana’s, and to stay united with a group of friends, several of whom are survivors of violence. They share laughter, worries and the common dream of starting La Mazorca.

Odetth also keeps going every day with her unending to-do list, the main ones: praying to God that today she manages to sell more than the taco and hamburger she sold yesterday, as well as supplicating him to take away a pain that is pressing against her chest and for COVID not to knock on her door.

Comments