Moraimen Gómez and her husband Teddy Dávila used contraceptives some months, but not others. They did it when they received public healthcare benefits or when they had enough money to buy condoms, pills or an injection, but, despite her best efforts, she got pregnant with her third child.

On a rainy October afternoon, Teddy carries the one-year-old baby in his arms, enters the house and Moraimen gives the child a kiss on the cheek. It’s a scene filled with love, but they both want to avoid another pregnancy. Their economic situation couldn’t support another child, Moraimen explains as water drips through a hole in the roof. She explained the cost of putting food on the table is harder with each new mouth to feed.

The uncertainty the family was living in was relieved a few months ago when a neighbor told them that Cepia, an organization in Huacas, was going to donate contraceptives called copper intrauterine devices, or IUDs.

At first, Moraimen didn’t think it was a good idea. “Several people have told us that the copper IUD creates problems, that it becomes ingrown, that it’s not safe and that it’s uncomfortable during sexual relations,” says the neighbor from El Llano, Santa Cruz (See infographic).

But she is now one of the 60 women between 19 and 45 years old that received a copper IUD in May and she says that all those myths have been dispelled.

But she is now one of the 60 women between 19 and 45 years old that received a copper IUD in May and she says that all those myths have been dispelled.

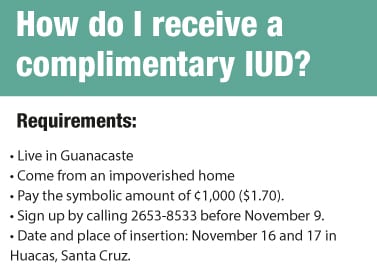

The organization donated the device and inserted it and provided medical attention for free. They also gave talks on family planning and sexual and reproductive rights. This month they will donate IUDs to 150 more women.

In the U.S., in the state of Colorado, a similar project that donated copper IUDs to adolescents and poor women helped reduce pregnancies by 40 percent in six years. The organization seeks to do the same and to help women gain better control over the number of children they wish to have.

Poverty Under the Microscope

For Cepia, poverty in nearby communities is, at least in part, the reflection of families that don’t have access to contraception. Its founder is Laetitia Deweer, a Belgian who studied family education in her country and created the organization to support education for at-risk children.

She says that one of the things that has pained her the most to see in these 13 years of operation is mothers of children who ask them for contraceptives or money to buy them. Others tell her about how depressed they are because of unwanted pregnancies.

We realized that the majority of impoverished women don’t have public healthcare benefits,” she said. In a recent study by Cepia, 22 of the 47 recipients of copper IUDs admitted to having problems affording to feed their children and 25 said they didn’t have public healthcare benefits.

“They can’t go to an Ebais to ask for a pill, an injection of condoms and they have to use their own money to buy them. Sometimes they only have enough money to pay for electricity,” Deweer said.

Deweer is right. Access to contraceptives is key for reducing poverty as it gives women control over the number of children they want to have. A study done by the United Nations Population Fund shows that access to contraception reduces fertility rates and that high fertility rates contribute to extreme poverty.

An analysis by The Voice of Guanacaste found that the potential for finding a salaried job is reduced as Gunacastecan mothers have more children. The more children they have, the fewer years of school they complete.

According to Costa Rica’s latest sexual and reproductive health survey, is that half of Costa Ricans didn’t plan their last pregnancy. Moraimen is a living model of this data.

The study revealed that women who live with a partner use pills with greater frequency (22%) as well as injections (9%) and condoms (9%). Despite the fact that the World Health Organization (WHO) says that IUDs are the most effective method, it is the least used in Costa Rica (only 3% of women use it).

Why? The myths and a lack of knowledge among doctors and nurses about how to insert IUDs scare women away from this method, according to Angélica Vargas, head of public healthcare system’s program for women.

The public health system found that there are doctors that don’t know how to insert it and we are holding trainings across the country,” she said. “We think there is going to be an increase in the use of intrauterine devices.”

Cooperation

Cooperation from locals and foreigners was key for Cepia’s project. The Paul Chester Children’s Hope Foundation, a U.S. organization that specializes in health, donated 1,000 devices after having a conversation with Laetitia Deweer about the main problems of the 17 communities where Cepia works.

International doctors came in May and will return in November for the second round of insertions.

Beach Side Clinic, located in Huacas, well lend it’s facilities and medical personnel to insert the devices while doctors at the San Rafael Arcángel clinic in Liberia will be in charge of providing free care for recipients of the IUDs.

Despite the alliances, it hasn’t been easy for participating women. In the first campaign, the foundation was planning to donate 120 copper IUDs, but they were only able to insert 60.

Another challenge is finding more gynecologists to provide care after insertion, because they will insert more than 100 devices during the second round.

Scaling the Project

After the second round, Cepia will still have 800 of the 1,000 copper IUDs that were donated. They plan to take them to other parts of the country through alliances with NGOs and private clinics.

“In San Jose, we already formed an alliance with the Clinica Biblica foundation to insert them,” Deweer said, adding that they also hope to encourage national health authorities to offer the devices to women without public healthcare benefits.

We want the public healthcare system to enforce the law that guarantees access without discriminating contraception methods,” Deweer says in one of Cepia’s classrooms.

About four kilometers (2.5 miles) from Cepia’s building, Moraimen prepares rice with milk that she will sell at one of the food fairs organized by women and the NGO so they can have a source of income.

When asked why she decided to use the copper IUD, she responds clearly, “it’s an opportunity that we should take advantage of in order to make sure we aren’t bringing unwanted children into the world, because life is hard.”

Comments