For the next two hundred years after Spanish conquest of the Nicoya Peninsula, European settlers, slave traders and soldiers, virtually all men, consorted with native women to create the creole society that exists today in Guanacaste. The large population of native people that existed when the conquistadors descended on Nicoya was substantially reduced by imported diseases and enslavement. The trade in cacao, that flourished in the late 16th century virtually disappeared as the population dwindled with the Spaniards untutored in the profitable cultivation of cacao while also beset by flotillas of pirates in their efforts to reach their chocolate-loving markets.

To replace cacao with another commercial export proved difficult and the small, dispersed fincas of the Nicoya region survived growing maize while keeping a few cattle. But the natives had a small, somewhat secretive skill, of removing the secretions of a royal Tyrian purple extract from sea snails, known as Plicopurpura pansa along the coast of Nicoya coast.

A small amount of colorant ‹purple› and the coloration on fabrics in color ‹purple›.

A small amount of colorant ‹purple› and the coloration on fabrics in color ‹purple›. Wikipedia

We know from documentation that the first Spanish expedition passed through the area now occupied by Garza, Guiones and Pelada (2) and that the native people harvested a purple dye from the secretion of this rare mollusk, managing the extraction without killing the snails.

This form of sustainable aquaculture, along with a well-honed ability for pearl-diving, proved to be their salvation, using small cotton patches to create thread dyed purple, sometimes woven cloth studded with pearls, becoming valuable in exchange for Peruvian gold before the invasions, and, later used for royal garments in Europe. The work was tedious and supply limited by the large number of sea snails needed to dyed cotton patches.

Sea snails from Mexico used to dyed cotton patch.

But by 1760, Charles III appointed to Nicoya, a Corregidor (mayor) Santiago Alfeiran, who ignored sustainability issues and ordered production tripled resulting in the complete extinction of the snails and a revolt that left the region in a state of chaos characterized by one scholar as a system of apartheid, with little or no social interchange between the native people, migrants from the Atlantic coast and the Spanish expats. In one account, no more than 300 people remained in Nicoya at the time.

The purple dye was prized in global trade since ancient times. In the 4 century BC, historian Theopompus reported that purple for dyes fetched its weight in silver (3). Aristotle described shellfish that produced Tyrian purple (4).

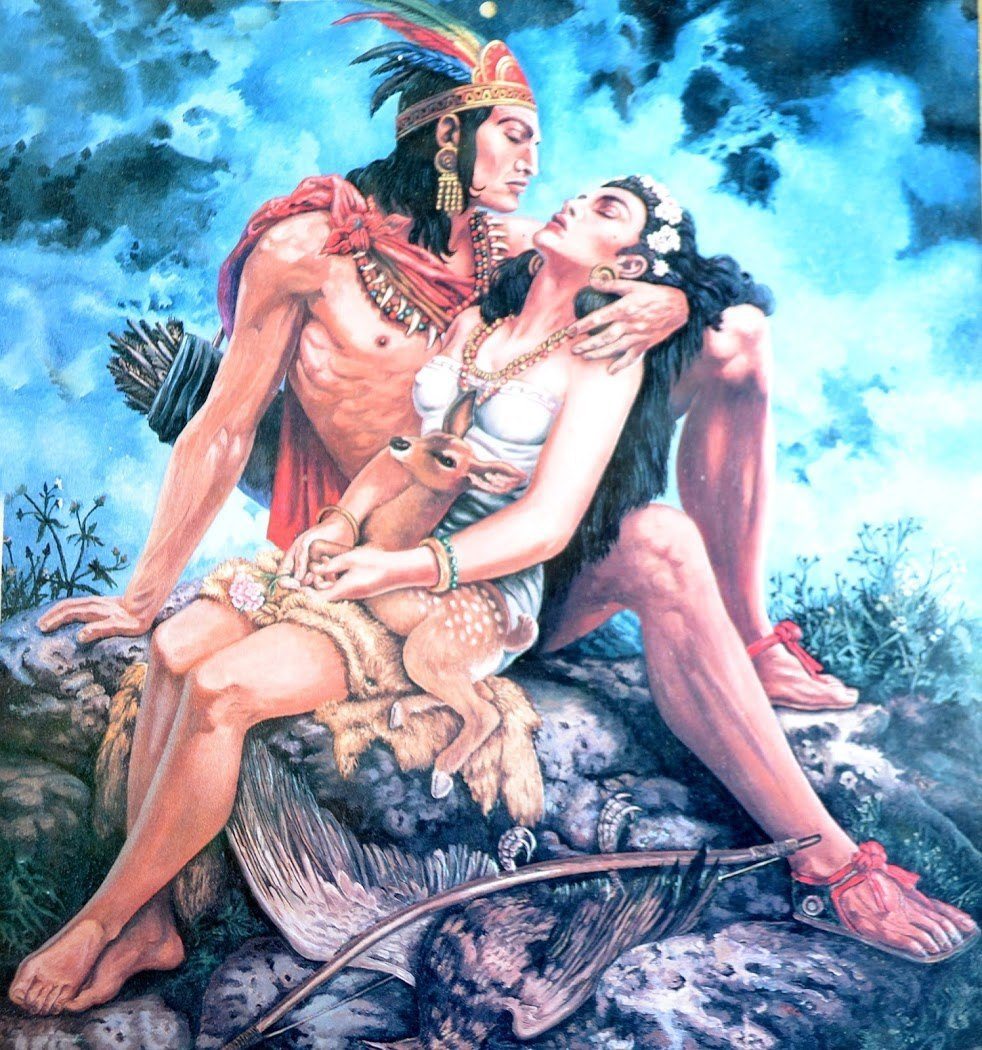

Mexican painting representing an Azteca warrior and his princess, dressed with cotton clothes and wearing jewelry made with pearls, corals and gold.

One can speculate that the trade in indigo or purple dye in the Nicoya area was derived from a reddish dye from a distinctive series of processes involving cacti and insects, a dye called grana, cultivated before the conquest in the Mixteca, in Oaxaca, the place where the native people of Nicoya originated (5). The dye became a major export to Europe and one can imagine that natural, non-fading dyes and cotton production drifted southward over the centuries before arriving in Guanacaste.

Perhaps of equal interest is the cultivation of Nicoya cotton. According to Harvard history professor Sven Beckert, the cultivation of cotton in the Americas dates from as early 2400 BC, with woven cotton cloth found in ancient Mesoamerican sites from the Aztecs to the Incas. Cotton growing, spinning and weaving was a family business for nearly five millennia, with evidence that purple-dyed cotton moved north from Central America to Mexico before colonization (6).

The moral of this story is that the delicate, labor-intensive processes of dye-making, cotton cultivation and weaving, whether in Mixteca or Nosara, required refined skill and painstaking diligence, work that the Spaniards left to the natives, inherited from generation to generation by the people of pre-conquest Nicoya until European civilization managed to demolish both the people and culture of Guanacaste.

The textile story is only one example of the nearly complete annihilation of Nicoya’s native peoples by disease, intermarriage and dispersal. Maize crops without a community of tenders withered. The population declined as climate, Central America politics and as an already thin population drifted east to grow cacao and later coffee for export to British and European ports. The period from the mid-1700s to the early-1800s in Nicoya lacks clarity in Costa Rican history, perhaps because it was neither here nor there, an island of abandonment by a disintegrating Central American colonial government in Guatemala in constant confusion, indeed, anarchy and by its rulers in Spain, preoccupied with problems at home. In any event, the records from that period were destroyed in a Nicoya fire in the mid-1800s.

Mexico’s war for independence in 1808 had followed the spirit of both the American and French revolutions, as the king of Spain abdicated and Napoleon assumed control. After an attempt by Mexico to gain control of Central America, on September 15, 1821, the Captaincy-general of Guatemala (formed by Chiapas, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Honduras) officially proclaimed its independence from Spain as the Captaincy-general was dissolved two years later. Shortly after Central America declared independence from the Spanish Empire, all of Central America (except Belize—British Honduras—and Panama, part of Colombia) were annexed by the First Mexican Empire in 1821 with Central America reforming itself into the Federal Republic in 1823, a government that continued to exist for the next 20 years (7).

Read more of the series “By our will”:

Chapter 1: The Arrival of Gil, The Conquistador, in Guanacaste

Chapter 2: Civilizing the Conquistadors

Chapter 4: Path Between the Seas

Chapter 5: Land of Opportunity

Chapter 6: Nicaragua y Costa Rica

Chapter 7: Celebrating Guanacaste

Chapter 8: The Costa Rican Railroad

References:

1) MacLeod, M. J. “The Search for New Industries and Trade” in Spanish Central America: A Socioeconomic History, 1520–1720, Austin: University of Texas Press, 2008.

2) 1760 Complementario Colonial, Expediente 315, Archivo Nacional de Costa Rica, variously cited in translation in Lawrence, John W., Archaeology and Ethnohistory on the Spanish Colonial Periphery: Excavations at the Templo Colonial in Nicoya, Guanacaste, Costa Rica, Vol. 43, No. 1, Historical Archaeology of Religious Sites and Cemeteries (2009), pp. 65-80.

3) Beckert, S., Empire of Cotton: A Global History, Vintage, 2014, pp. 9–15

4) Minster, C.. “The Federal Republic of Central America (1823–1840)”. Latin American History. http://latinamericanhistory.about.com/od/historyofcentralamerica/a/09republicofCA_2.htm

5) Ibid., MacLeod.

6) Beckert, S., Empire of Cotton: A Global History, Vintage, 2014, pp. 9–15.

7) Minster, C.. “The Federal Republic of Central America (1823–1840)”. Latin American History. http://latinamericanhistory.about.com/od/historyofcentralamerica/a/09republicofCA_2.htm

Rosenbaum has been a researcher and consultant on sustainable tourism and community development for USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and the World Bank in several countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. In addition, he has published more than half a dozen books on cultural issues as a senior researcher at George Washington University. Due to his own personal interests – he lived in Nosara and visits Guanacaste often-, Alvin decided to delve into the history of Guanacaste to understand this environment in the best way possible: by incorporating variables from the past into the analysis done going forward, to understand the present and the future of this land that welcomed him with open arms. Alvin spent many hours and several months systematizing all of the information from books and interviews and talking with Guanacastecans who are well-versed in local history to finally produce a series of installments titled “Por Nuestra Voluntad” (By Our Will).

The chapters of the series By our will are the author’s opinion and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of this newspaper. If you want to write an opinion article, you can write to [email protected]

Comments