In these pages I have been writing about the traditional, pre-Columbian region called Gran Nicoya that included all of Guanacaste and extended north to Lake Nicaragua and on to Léon. As history proceeded, in the region that includes parts of today’s Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the people learned to speak Spanish instead of the local languages they had before the arrival of the conquerors.

Their countries each have shores on two coasts, experience volcanoes and earthquakes, hot lowlands and cool highlands. What is different, in this author’s opinion, began with the first European to arrive on Central America’s Pacific coast, Gil González Dávila, who purchased slaves in Panama from Pedrarias Dávila, the colonial administrator. From Panama he took eleven African slaves to the newly-founded Nicaragua (1). While later reports show Gil owning 200 Indian slaves in Panama, they were a fast-declining source of labor due to European diseases or by simply scattering when African slaves arrived to plant cane, raise hogs for tallow and cured meat and train horses that forged links with the Imperial economy.

The underlying difference between Nicaragua and Costa Rica is rooted in slavery.

Spanish conquest of Nicaragua was brutal and complete (2). Costa Rica, by contrast, in the late-16th century, was barely populated, with little wealth and virtually no trade. Slavery, when it existed in Costa Rica, was practiced by the few who were wealthy and considered an oddity while it became the backbone of Nicaragua’s economy for the next 250 years. With the Catholic Church issuing confusing and contradictory edicts on slavery, it continued to flourish until 1824 (a propitious year) when slavery was outlawed in Nicaragua.

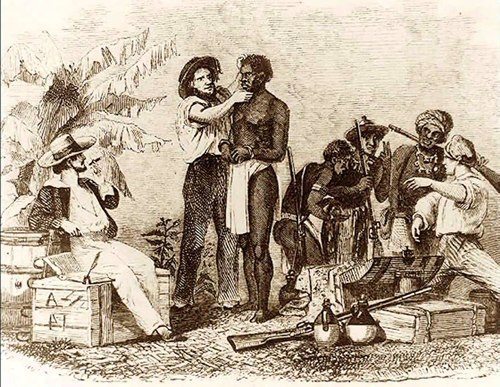

Illustration of slavery in Central America.

Nicaraguan government has been always authoritarian while Costa Rica, albeit with several dictators in its history, mostly moved forward as a rural democracy, its neighbor nearly always in chaos and civil war.

But when considering the differences in national identity between Costa Rica and Nicaragua, the position of slavery, like in the American North and South leading to civil war, was a metaphor for significant cultural differences between these two countries that accumulated after Spanish conquest.

The integration of Guanacaste into Costa Rican culture and history may be best expressed by the opposite: The integration of Costa Rica into Guanacaste history, based on the dynamics of border disputes, the territorial ambitions of William Walker and the historical maxim that a country’s borderlands tend to be the theater of the greatest conflicts that, in turn, mold a distinctive theme for its national identity.

In the 18th Century a few wealthy families in the Rivas area—in the heart of Nicaragua’s colonial society—began to establish their houses and fincas in the northern part of the Nicoya Peninsula in the triangle that connected Bagaces, Nicoya and Rivas. The place was called Guanacaste after the grand tree that grows in these parts. In 1824 the territory of Guanacaste was annexed to Costa Rica. In 1836 the town of Guanacaste was declared capital of Guanacaste province, renamed Liberia in 1854.

While a consensus was evolving among the Costa Rican 19th century elite to the story of its origins, the conventional wisdom of that period was to place emphasis on two differing but compatible cultures: “agrarian democracy” and the glory of its European origins.

The agrarian democracy thesis is based on the notion of a modest, cooperating folk with wealth distributed throughout the country based on progressive and practical efforts throughout the 18th and 19th centuries to populate the hinterlands with modest yeoman farmers. This differed from the rest of Central America where governments and oligarchs tended to be centralized, undemocratic and less modern with great plantations worked by slaves.

But Guanacaste, with its ancient roots as Gran Nicoya and a transitional landscape and people between the Central Valley and Lake Nicaragua cultures, has always captured the drama and romance of a mixed-race frontier society.

The alternative view was that Costa Rica was a “white” European country, validated by the government’s invention of traditions that reinforced its role as a reliable trading partner having prestige in foreign capitals. Indeed, President Taft called Costa Rica the “Switzerland of Latin America” in 1912 while Nicaragua, now and then, maintains a reputation for instability and poverty controlled by authoritarian governments.

Read more of the series “By our will”:

Chapter 1: The Arrival of Gil, The Conquistador, in Guanacaste

Chapter 2: Civilizing the Conquistadors

Chapter 4: Path Between the Seas

Chapter 5: Land of Opportunity

Chapter 6: Nicaragua y Costa Rica

Chapter 7: Celebrating Guanacaste

Chapter 8: The Costa Rican Railroad

References:

1) Chamberlain, R.,The Conquest and Colonization of Honduras 1502-1550, Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1953.

2) Drescher, S., “Abolition of Atlantic Slave Trade,” Princeton Companion to Atlantic History, Princeton University Press, 2015, pp. 57–59.

Rosenbaum has been a researcher and consultant on sustainable tourism and community development for USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and the World Bank in several countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. In addition, he has published more than half a dozen books on cultural issues as a senior researcher at George Washington University. Due to his own personal interests – he lived in Nosara and visits Guanacaste often-, Alvin decided to delve into the history of Guanacaste to understand this environment in the best way possible: by incorporating variables from the past into the analysis done going forward, to understand the present and the future of this land that welcomed him with open arms. Alvin spent many hours and several months systematizing all of the information from books and interviews and talking with Guanacastecans who are well-versed in local history to finally produce a series of installments titled “Por Nuestra Voluntad” (By Our Will).

The chapters of the series By Our Will are the author’s opinion and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of this newspaper. If you wish to write an opinion article, contact us at [email protected]

Comments