In my last column I presented a contrast between Nicaragua and Costa Rica as a path to understanding our differences and the evolution of Guanacaste history and the constituent parts of its culture.

Costa Rica did not experience a moment of Independence, but, instead, celebrates patriotism and national identity each year with the anniversaries of the Battle of Rivas against William Walker (April 11) Annexation Day (July 25), and September 15, 1821, the day of the final Spanish defeat in the Mexican War of Independence (1810–21), when the authorities in Guatemala declared the independence of all of Central America. Costa Rica did not declare its complete independence as a sovereign nation until 1847.

All these observances, as a demonstration of a nation ready to conduct global trade and the patriotism of its population provided Costa Rica with a sense of its independence and solidarity. This column explores how the national hero Juan Santamaria came into his own as the symbol of independence and, implied, its superiority as a democratic country.

In 1890, to make trade deals and to borrow money to build the Costa Rican Railroad, the government and business community in San Jose had to be presented as modern, sophisticated and creditworthy. Inventing traditions were not particular to Costa Rica but typical, refined and articulated most elegantly by the British who became Costa Rica’s principal trading partners and bankers in the late 1800s. Costa Rica, like most of the rest of the developed world, began in this period to project to its trading partners stability, a cultural identity and pride.

In the mythmaking department, Costa Rica has a respectable track record. In 1885 Guatemalan dictator Justo Rufino Barrios announced his plans to reunite the isthmus into the Federal Republic of Central America (once again) even as no other country was so inclined.

Costa Rican leaders needed a symbol of unity and bravery to consolidate its national identity. They picked Juan Santamaría, a hero of the 1856 Second Battle of Rivas against William Walker who arrived in Nicaragua with his filibuster army to take over Nicaragua’s government, becoming its ad hoc president for nearly two years.

As it turned out Juan was almost perfect as a hero. He was a working-class campesino, not a president or general. Unfortunately, he was the third person to try to burn the garrison. The first, a lieutenant, didn’t die in the battle. The second soldier did die, but was a Nicaraguan. So that left Juan, a mixed-race impoverished drummer boy, who burned the garrison where the enemies were hiding and 35 years after his death, became the national symbol of independence.

Juan Santamaria statue. Photo by Rodrigo Fernandez.

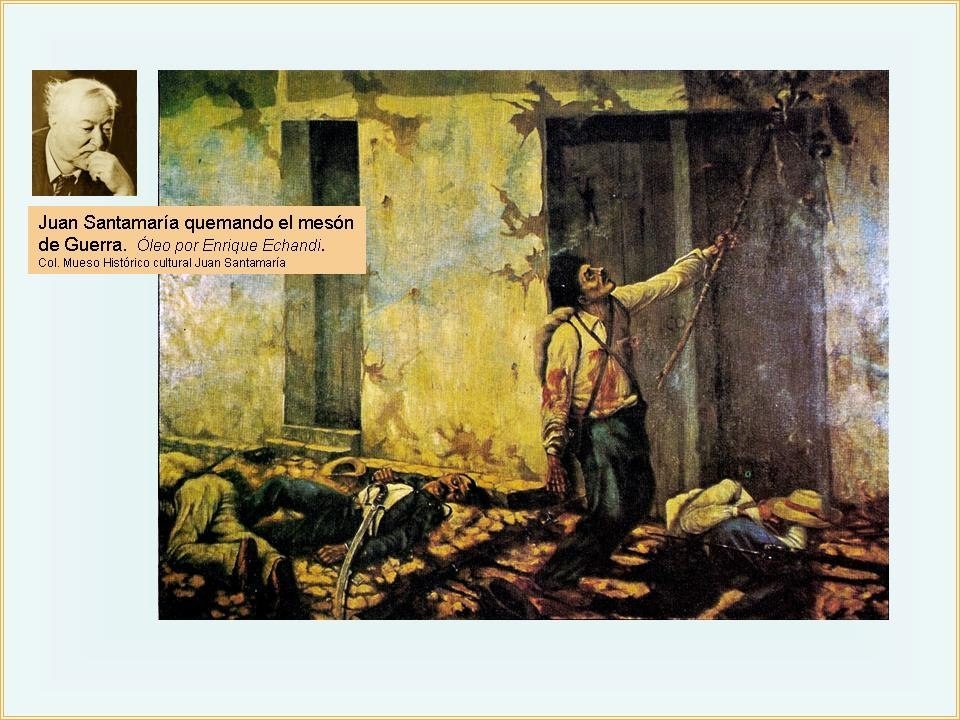

The government erected a statue in 1891 (currently standing in his hometown of Alajuela), of this local hero looking like a French soldier. A decade later, tico artist Enrique Echandi Montero painted Juan as a ragged peasant with mulatto features.

The burning of the Meson by Enrique Echandi Montero

As one may imagine, the depictions of Juan in school textbooks, at his eponymous airport and on the national Juan Santamaria holiday are based on the statue, not the painting (2).

Let us look at two examples from that era in Europe and it effects on Costa Rica. This is a country’s public relations for itself, circa 1890.

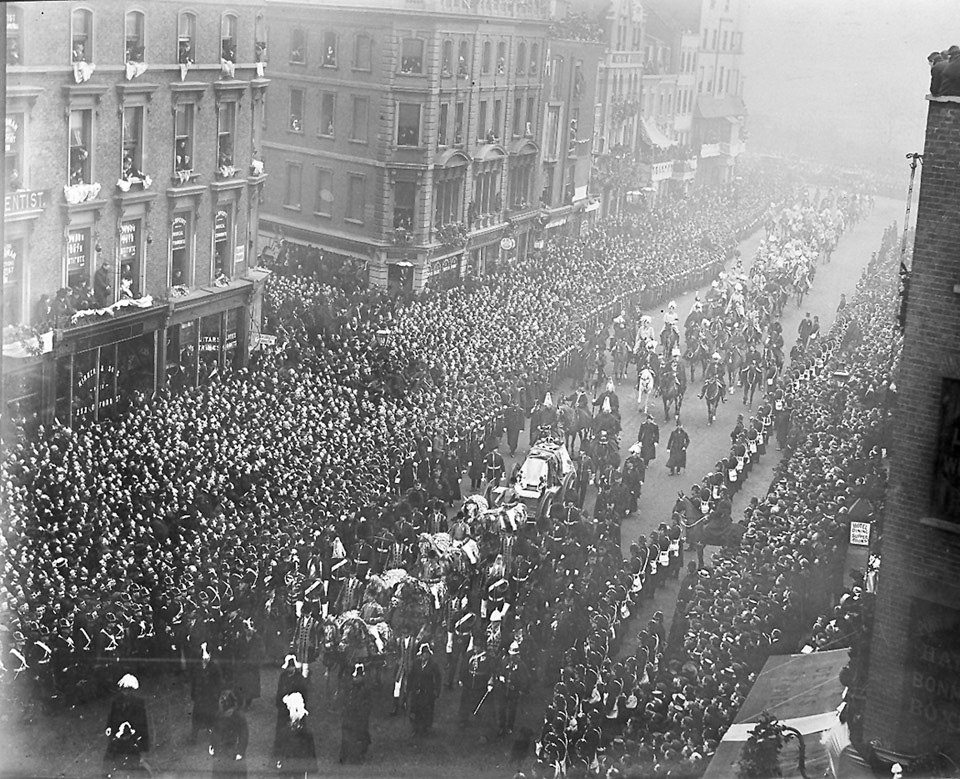

The period was replete with grand ceremonies, processionals, pageants and planning for their settings developed as competition among rival countries led to symbols of the glorification of public history as provincial fiefdoms were replaced with nationhood.

The funerals of Queen Victoria, Alexander III of Russia, Kaiser Wilhelm I and Victor Emmanuel II were all magnificent, splendid affairs, all designed to appear to be imbedded in grand ancient tradition but, in fact, were mostly created from whole cloth at the moment they were needed. Before 1860, such ostentation and respect for historical precedent in the ceremonial was rare if not even imagined. Queen Victoria when alive, refused scepter, crown and ermine and only very occasionally appeared at Parliament or in public.

Funeral Queen Victoria, England.

Another curiosity from the era was the establishment of Republic of Costa Rica Independence Day, September 15, 1821, which was the date of the Spanish defeat in the Mexican War of Independence, establishing a date that was 27 years before the actual fact. Costa Rica joined the United Provinces of Central America in 1823, which also included El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. Costa Rica became fully independent under Braulio Carrillo Colina in 1838 but it was not until August 31, 1848 when head of the province, Jose Maria Castro Madriz, formally declared Costa Rica an independent and sovereign republic.

Read more of the series “By our will”:

Chapter 1: The Arrival of Gil, The Conquistador, in Guanacaste

Chapter 2: Civilizing the Conquistadors

Chapter 4: Path Between the Seas

Chapter 5: Land of Opportunity

Chapter 6: Nicaragua y Costa Rica

Chapter 7: Celebrating Guanacaste

Chapter 8: The Costa Rican Railroad

References:

1) Díaz Arias, D., Historia del 11 de abril: Juan Santamaría entre el pasado y el presente, Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica, 2006. See also Steven Palmer, Getting to Know the Unknown Soldier: Official Nationalism in Liberal Costa Rica, 1880–1900, Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Feb., 1993), pp. 45-72.

2) Brenes Tencio, G., Iconografía Emblemática del Héroe Nacional Costarricense Juan Santamaría, ACTA Republicana Política y Sociedad Año 7, Número 7, 2008. See also, Alejandra Murillo, Reconstruction of the Campaign of 1856 and its hero Juan Santamaría online at https://huellasculturales11.wordpress.com/trabajos-de-los-estudiantes-ii-semestre-2011/la-reconstruccion-de-la-campana-de-1856-y-su-heroe-juan-santamaria-por-alejandra-murillo/

Rosenbaum has been a researcher and consultant on sustainable tourism and community development for USAID (United States Agency for International Development) and the World Bank in several countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. In addition, he has published more than half a dozen books on cultural issues as a senior researcher at George Washington University. Due to his own personal interests – he lived in Nosara and visits Guanacaste often-, Alvin decided to delve into the history of Guanacaste to understand this environment in the best way possible: by incorporating variables from the past into the analysis done going forward, to understand the present and the future of this land that welcomed him with open arms. Alvin spent many hours and several months systematizing all of the information from books and interviews and talking with Guanacastecans who are well-versed in local history to finally produce a series of installments titled “Por Nuestra Voluntad” (By Our Will).

The chapters of the series By Our Will are the author’s opinion and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of this newspaper. If you wish to write an opinion article, contact us at [email protected]

Comments