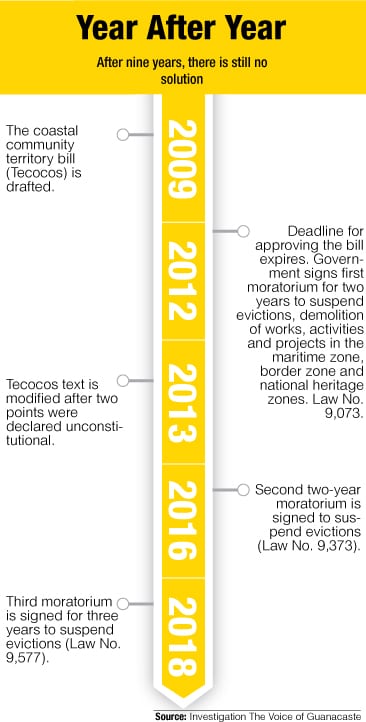

From moratorium to moratorium. That’s how congress and the last three governments have solved the lack of consensus around passing a law that recognizes the rights of people who have lived in the maritime zone for more than 10 years.

The coastal community territory bill, known as Tecocos, has been presented as a potential solution to this problem. The bill proposes creating 64 zones (coastal territories) under a national protection system.

In June, upon failure to approve the bill, President Carlos Alvarado signed a new law (Law No. 9.577) in order to prevent people from being evicted or having their works, activities, projects or businesses removed over the next three years if they are in the maritime zone, border zone or areas considered national heritage sites.

Without a law, residents in these areas continue in legal limbo since they have no documentation that guarantees their presence in these areas.

The president said in a statement that he hopes this three year period will give Congress enough time to debate, analyze and pass legislation to bring appropriate order to these areas. He added that the moratorium doesn’t apply to cases in which a judge or a city hall has ordered an eviction due to environmental threats.

With Alvarado’s signature, the third moratorium in the last three years was passed. It protects residents in coastal zones from eviction. But those who don’t have property titles for their land are prohibited from selling, expanding or repairing their homes, for example. (See timeline)

Edith Castillo, born in Playa Garza, says that people in the coastal zone are worried.

“Our house is here and we don’t want to move far away from the things we need to live, like the beach,” Castillo said. “It’s not just Garza, it’s Barco Quebrado, Buena Vista and a bunch of other communities.

Consensus. What for?

Researcher Dionisio Alfaro recognizes in his report “Territorial and Maritime Zoning in Costa Rica: Steps for Formalizing it as a Public Policy” that families across the country have lived in these special zones (coastal, border and heritage) for decades.

According to the document, many of these families don’t have a government concession granting them the right to live in these zones despite having lived there and used the land for long periods of time. As a consequence, some families have had to face government mandated evictions and the demolition of their buildings.

“This unleashes a serious social problem because you leave these people without a roof and, in many cases, without access to the productive activities that they lived off of,” the report says.

These families, Alfaro said, have built their homes and existence in these areas, living off of activities such as fishing, local tourism and farming, among others.

The Tecocos bill estimates that, upon approval, more than 60,000 people would have the right to live in maritime zones across the country.

In order to approve the bill, there must be political consensus among the lawmakers in Congress, something that has not yet happened.

Aida María Montiel, congresswoman for Guanacaste from the National Liberation Party, said that Congress will work on a solution to the problem, but she doesn’t see an easy path forward for it.

“The president signed the moratorium and now everyone has forgotten that we need to debate the issue,” she said.

She added that reaching an agreement won’t be easy and that legislators from coastal provinces will have to meet in order to find a solution.

For José María Villalta, congressman for the Broad Front party, the coastal territories bill (Tecocos) must be revived and considered since there is political will to approve in this congressional period.

“We have a different Congress with a different composition this time,” he said. “We can reach accords.”

Villalta hopes that the moratorium signed by President Alvarado is the last one the government has to sign.

Comments