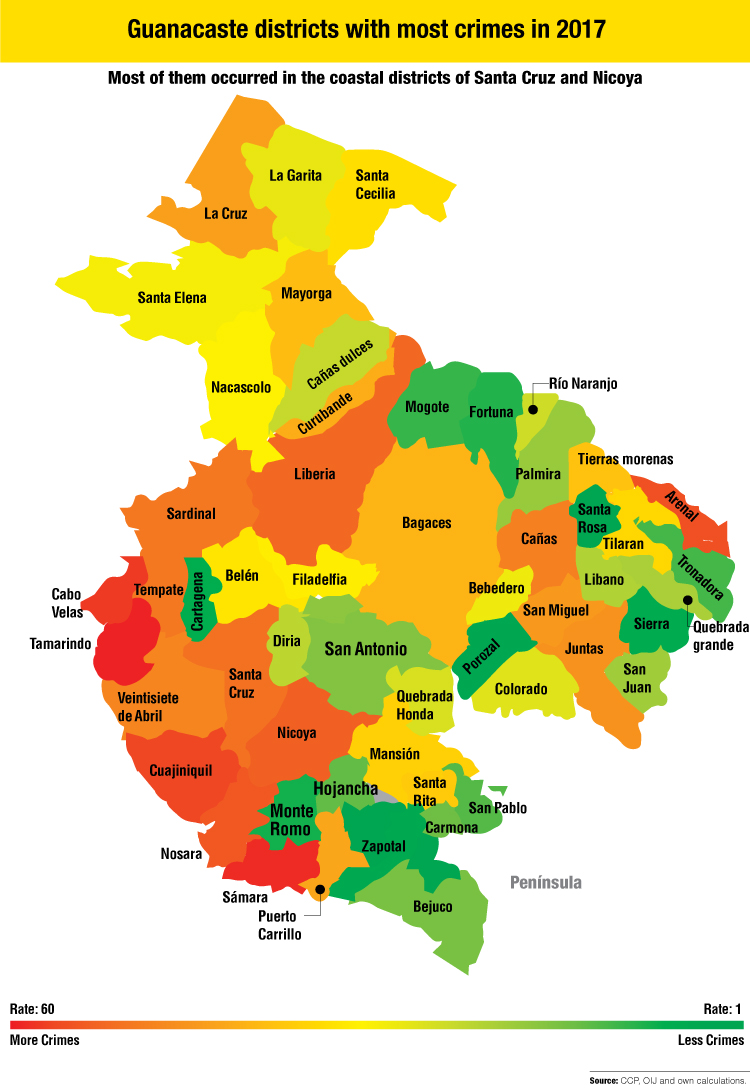

The coasts of Guanacaste face a problem of growing insecurity. It’s not just residents who say that. Data confirms it. Between 2013 and 2017, crimes increased 36 percent in 17 coastal districts in the province.

While in 2013 the average crime rate was 14 per 1,000 residents, that number rose to 19 in 2017 and showed a growing trend almost every year.

This growth was even more pronounced along the coasts that have less population than the central cities of each canton, which have more inhabitants, and therefore are expected to have more crimes.

In the districts with more population, crimes went from 15 to 16 per 1,000 inhabitants in the same period.

This is evidenced in a data analysis done by The Voice of Guanacaste using criminal complaints filed with the Judicial Investigation Police (OIJ).

Tamarindo and Samara are the towns that registered the highest rate of crimes per 1,000 residents between 2013 and 2017. Both districts are tied with average rates of 41 crimes per 1,000 residents during those five years.

The numbers are even higher in Sámara and Tamarindo since, in some cases, people don’t report crimes because the police station and OIJ offices are several kilometers away from the beaches.

To compare, while Tamarindo registered 60 crimes for every 1,000 residents in 2017, Jacó, Puntarenas, recorded 34.

Jacó reduced the crimes from 39 per 1,000 residents in 2013 to 34 in 2017. The police said that it had carried out prevention campaigns among tourists, with brochures and information to take care of their belongings and be alert to thieves.

Jacó officials also make roadblocks at the entrance and exit of the beach and this has resulted in the seizure of weapons and identification of criminal gangs, said the regional subdirector of Puntarenas Police, Mauricio Guevara.

Neighbors Are Organizing

There is a lot of tourism and a low police presence along the coasts, a combination that, according to sources, makes the problem worse.

Residents are worried and are taking actions to improve the situation.

For example, Sámara representative Bonifacio Díaz presented a motion before the Nicoya city council requesting a meeting in the community during the first week of September to coordinate actions among residents, police and the local government.

“There’s a lack of interest on the part of the development associations in the district of Sámara to organize and reduce crime,” Diaz said. “We hope that with the September meeting we can get better organized.”

President of the Sámara Development Association, José Fulvio Paniagua, accepted that his crew hasn’t taken any steps to improve the problem and said that he hopes that this changes at the next meeting, which will be held in his community.

In Tamarindo, the town most affected by crime in 2017, the development association has tried to arrange for the construction of a police station for the last five years, but has not had any success, said association vice-president Trevor Bernard.

“The issue is, who is going to pay for the construction? We are currently seeking financing from the ICT (Costa Rican Tourism Institute) or Dinadeco (National Department for Community Development),” Bernard said.

While the national police’s mobile station was present in Tamarindo for several months, it was closed in 2017 by the health ministry because it didn’t have an integrated bathroom and because the unit (which is a type of container that moves around communities) isn’t supposed to spend so much time in one place. Now, these police officers are distributed among Santa Cruz, Brasilito, Flamingo and a few days in Tamarindo, says Bernard.

Tamarindo’s ADI continues pushing for construction of a police station and stays in constant communication through a Whatsapp group to alert and coordinate with residents, merchants and business owners, according to the association’s administrative assistant José Carlos Sequeira.

“We have a very dynamic, interconnected community watch system,” he said.

In the two years of the group’s existence, they have identified the most vulnerable zones in Tamarindo and now are able to better coordinate community watches with the national police and the tourism police.

In Tamarindo the officers have handed out brochures in English and Spanish to the merchants and tourists of this coastal community, so they be aware of their belongings.

Few Cops and Insufficient Resources

In Sámara and Tamarindo, the two areas with the highest crime rates, police reports can’t even be filed. Victims in Sámara must go to Nicoya and those in Tamarindo have to go to Villarreal.

Sámara police chief Omar Granados said that their information system is obsolete and they send victims to the OIJ, which is located 36 kilometers (22 miles) from the community. Many don’t even file a report because of the distance they must travel.

In Tamarindo, there isn’t even a police station and people must go to the Villareal station, located six kilometers (3.7 miles) away from the coastal town.

The low number of police officers is another one of the limitations that both stations face. Granados said that Samara has no more than 10 officers and has only one patrol for surveillance rounds and Tamarindo must receive assistance from the tourist police in Flamingo – 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) away from downtown Tamarindo – and support from the Villarreal station.

Floating Population

Tourism boosts the country’s income, but unfortunately it doesn’t escape a coastal reality: criminals are going after tourists.

“The population can’t be viewed as only those who vote (or live) in the district,” said regional police chief Kattia Chavarría. “There is a very large floating population, which increases crime.”

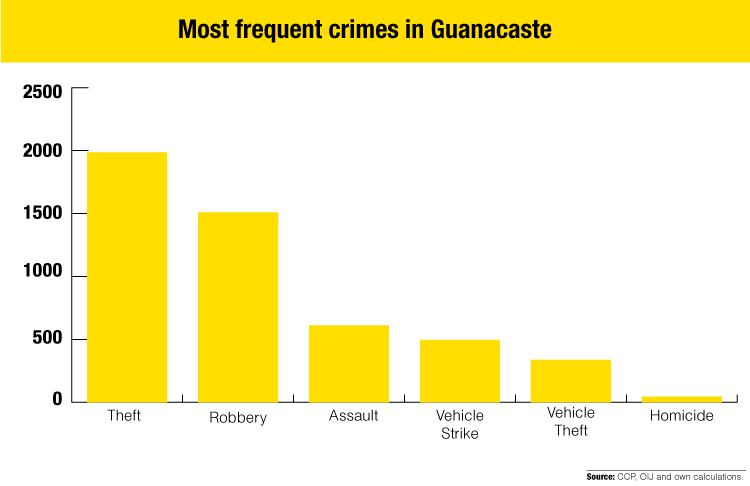

“Robbery is the most common crime along the beaches because many tourists leave their belongings unwatched and this makes it easy for criminals to take things without having to resort to violence or physical force,” she added.

Sámara police chief Omar Ganados shares this perception. He estimates that in low tourist season, some 300 visitors go to the beach each day, while in peak tourist season more than 1,000 people visit the beach daily.

In Tamarindo, chief of tourism police Luis Sánchez estimates that more than 1,500 tourists visit the beach on a daily basis.

Comments