After several kilometers driving along a gravel road while swallowing dust, the map tells me that the ravine to my right is an entrance and that this is where Auxi lives. “Keep climbing. Climb and climb and climb, and at the community center take a right,” a Guanacastecan man with his shirt open told me a long while ago.

The ravine turns out to be the entrance to Auxi’s house, but what comes next is like something out of a movie when someone walks into a closet and comes out the other side to find an unexpected, marvelous world. I look to my right and, in the distance in the middle of the sea, the center of the Gulf of Nicoya, rests Chira Island, looking as if it were painted in watercolors.

When they said that beauty doesn’t come easy, I think they were referring to Bella Vista. This town of roughly 40 families and a name that says it all rises above southeast Nandayure and is where Auxiliadora, Grettel, Elieth, María del Carmen, Ana Lucía, Sussan, Juan Diego and Josué Carranza Montero grew up. They’re eight siblings educated in a school with one teacher and went to a rural high school where the beauty and scarcity of this inhospitable paradise refined their bittersweet future.

Grettel, Auxiliadora and Ángela prepare lunch for their family and bread for later. In an hour, everyone else will show up. They are out picking coffee.

Grettel sits on the table outside with her back to the sea, her hair in a bun with honey-colored eyes. She smiles tepidly, apologizing for the harsh 10:30 a.m. sun, though it’s actually breezier here than in the rest of the lowlands.

She furrows her brow when she tells me that, a couple decades ago, during her first days at the University of Costa Rica’s main campus, she had to do a general studies thesis with a group of kids that had recently graduated from Humboldt, a private high school in San Jose that is unaffordable for most mortals. She, on the other hand, had gone to the single-teacher Bella Vista school where they barely had Spanish class. Then she enrolled in the Nandayure Technical Professional High School where the only English they learned was “Hello teacher” and some professors abandoned them for months.

The most recent report on the state of education shows that when Grettel and several of her sisters enrolled in the UCR, the number of low-income children like her who made it to college was minimal. Just six percent back then, and it has grown to 11 percent today.

Her classmates from richer high schools had more opportunities, not just economically but statistically as well. Since 2005, more than half of children from the richest fifth of the population make it to college.

Grettel and her sisters were born in a place where you eat what you grow and not cause of the farm to table craze, but for necessity. Still, she made it to college and was part of the minority.

But the Humboldt kids decided to analyze a book in German “Imagine, they (her classmates who graduated from Humboldt) stuck me in everything but I didn’t do anything.” Grettel puts her hand on her forehead with her elbows resting on the table with a look of reproval.

“That’s a really good high school, really really good,” she says. “And I came from a high school where the teaching method was copy the blackboard or we’ll dictate the material to you and that was it,” she says while Auxiliadora, her sister, serves mango juice and home-baked cookies.

Grettle was 19 when she entered college. She studied geography for two years and then gave up. Lectures were in English and sometimes even in French. “What halted me was secondary education.” Immediately, she got married and had a daughter, but a phrase got stuck in her head. “I failed out of the UCR.” She used to blame herself. “I should have tried harder.” But years later, and without her hand on her forehead, she says that life has helped her redistribute that blame.

In Spite of it All

The stove is woodburning. For lunch there is chopped plantain with ground beef, rice and beans. Ángela, the mother of this crew of grown women, kneads dough on a metal table for a loaf of bread filled with jam.

Her eyes light up when she starts to remember. “You’ll graduate, whether you want to or not,” Sussy, the youngest of the girls, remembers her mother saying when she had a bad exam. But once, their father told several of the daughters that he was no longer going to take them to school, and the matriarch of the family didn’t smile then. “Over my dead body,” she remembers her saying.

Ángela heard recently that children whose parents didn’t go to college were less likely to finish high school. A few days later, a researcher for the state of the education report named Dagoberto Murillo would tell me the same. There is a correlation between a low level of education in the household and the level of education the children reach.

In other words, more than where we come from, the family we come from determines where we end up, but….

“There are always rural, coastal and distant areas that have a less favorable education situation and in these zones, low-levels of education prevail,” the researcher explained to me.

The Carranza Montero family is, in all senses, an exception. Grettel studied English education in a private university when her daughter was three years old. Her desire to study geography at the UCR was long gone. She worked at a hotel and in a call center in order to improve her English, but she’s happy now to have pushed herself because she loves her job as an English teacher in Cindea.

María del Carmen, 34, took 10 years, but was able to finish statistics at the UCR while she raised her children. She now works at INEC in San Jose.

Auxiliadora, de 28 años, has several degrees and worked in Alajuela and Liberia as a chemical laboratory technician and now has a small business selling sauces for meat and jelly. She says that the majority of her classmates from school are working in the central valley because there is no work here. “This is a center of expulsion,” Grettel says.

Elieth, Ángela, Auxiliadora, Daniela and Grettel spend their vacation together at their home in Bella Vista.

Ana Lucía, 24, is finishing her studies in topography engineering at the UCR main campus and Josué enrolled in TEC. He will find out about a scholarship he applied to in a few days. Elieth, 31, went to the United States and Sussan, 21, is earning an English certificate.

But getting to this point meant swimming against the current their entire lives. In order to study at the UCR, Grettel and María del Carmen put individual mattresses on the floor of their aunt’s one room house in San Jose where they slept, ate and studied. Their aunt had three children and made them do chores, but it was what was available.

It was that or nothing, Ángela says with a bakers hat on.

“They had a really hard time. It was hard for them to study, but I would tell them that they couldn’t quit, they had to continue. This can disappear, but your studies never disappear. It’s like what you’ve already danced and eaten. No one can take it away from you. It dies with you.”

The Elite

A while ago, Anita, Sussy, Josué and Olman, the father, came in from picking coffee. They are all eating in silence, with a spoon, sitting in chairs in the living room. At times they say jokes in hushed voices and laugh.

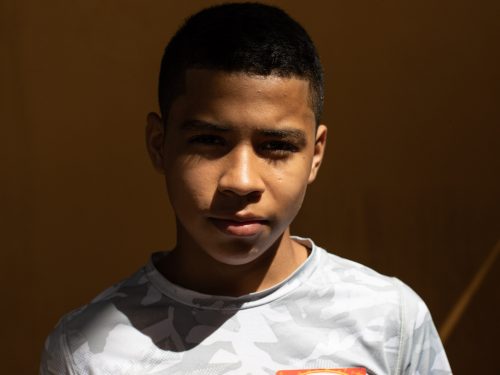

Josué is the youngest. He’s long, thin and courteous. His sisters melt with praise for him. He likes to play the rubik’s cube, he’s well-behaved, disciplined, brilliant, “cut from Sunday cloth.”

He takes high school courses in rooms built of drywall and recycled cans and where brain boils and the girls don’t know how he manages to study. He was without a math teacher for half of last year.

When they found enough money to take him in for an entrance exam at the San Pedro scientific high school, he didn’t pass. But it wasn’t because he wasn’t able – he was accepted to the TEC’s maintenance and materials engineering program – rather because he competed at a clear disadvantage with kids that came from San Jose high schools.

Angry, Grettel sent an email to the then minister of education, Sonia Marta Mora, on December 4, 2016 at 7:26 p.m.

“This year, the students that were accepted by said institution, according to what I could see on the list, came, in large part, from private high schools. One of the teachers told us, ‘We are elite.’ While I thought she was talking about the academics, I realized that it’s also an elite group of students mostly from middle, upper-middle and even upper middle class.”

The minister sent the email to the deputy minister of academics. “After that, nothing happened,” Grettel said.

A couple decades after enrolling in the UCR and “failing” as she says, Grettel sees the panorama with a broader perspective and spreads out responsibility.

“It seems to me that this situation highlights inequality, because if we look at it in that light those who were accepted are those who have the best averages in tests and entrance exams for public universities.”

We don’t know how many kids like Josué aren’t able to get the education they want despite being intelligent. Researcher Dagoberto Murillo says that there are no data to follow up on each kid from the point he enters school until he finishes college. How many kids were born to be Franklin Chang, but only made it half-way because the barriers to get there were too high to climb over? The studies we have at the moment don’t give us enough information.

For example, it’s impossible to know how many children from single-teacher schools graduated high school or college, much less what their IQs were or what level of education they may have reached. But Grettel is sure of one thing. “My brother, like thousands of kids in this country, will continue to fight from a position of disadvantage in order to get a quality education.”

Luck

The single-teacher Bella Vista school is a mile from Auxi’s house, who is walking with me along with Grettel and their young nephew Benjamín. It’s painted blue and it has a greenhouse in the back with a garden where they pick food for the cafeteria.

Right beside it on the same property is the home of Yessenia Padilla, the teacher. She’s tall with tan skin, sweet and affectionate. She has always been like a second mother to the kids and knows the families well.

Yessenia Padilla taught five of the eight Carranza Montero siblings.Photo: Maria Fernanda Cruz

Later, she will tell me that she too studied in a school like the one she teaches in now and her son José Carlos and her nephew Ramsés also went to a similar school in Puerto Jesús, Nicoya. They now study in public universities in San Jose and Nicoya.

In order to increase education coverage in risperse, rural areas like this one, Costa Rica built single-teacher schools between 1950 and 1970 throughout the country. The struggle now is improving their quality. Very few give English and computer classes, two urgent needs in order to provide kids with the tools necessary for a scientific and technology-driven future.

Auxi never received English classes, but her younger sisters had a few lessons each week. “It wasn’t much, but it was something. At least I can say Hello,” Yessenia says as she laughs.

The school’s surroundings look like a typical town. The plaza, church, convenience store and a tons of dust. “It was paradise,” says Auxi, who faced limits and suffered from unfulfilled dreams because of this faroff paradise, Bella Vista de Nandayure. But she doesn’t doubt her happy childhood.

Comments