More than one of us has childhood memories full of chaotic family trips to the beach, which are worth repeating. Mine are so fresh that, at age 29, I feel like they were just last year. Grandpa Beto asking at the last minute to have his “gurupera” packed (his thong for swimming) and the 1988 Isuzu Trooper crammed full of cousins.

Ignoring both traffic and physical laws, we were able to fit everyone in the car with coolers and pots and pans, and start a trip that, as a child, felt like an eternity.

After unloading everything at the shore, the rest of the day transpired with a series of popular rituals that, even today, can be seen at many beaches in Guanacaste and that, according to the ICT. The preferred by Ticos, according to this PowerPoint done six years ago by the Costa Rica Tourism Institute about vacation habits.

One of them is Puerto Carrillo, in Hojancha, where Angie, 28, turns a semi-charred hot dog with a half-melted plastic fork. “We came to see the sunset and escape from the routine a little,” she tells me on sunny Sunday November.

Her youngest son, Donovan, devours the hot dog with his hands full of sand. A few meters away from them, Fiona, the oldest, buries herself in the sand once more even though they have cleaned her twice.

These family outings to the coast represent 73 percent of the internal tourism that occurs almost always at the end of the year when the leaves of the trees are dry and the leaves for tamales are cleaned.

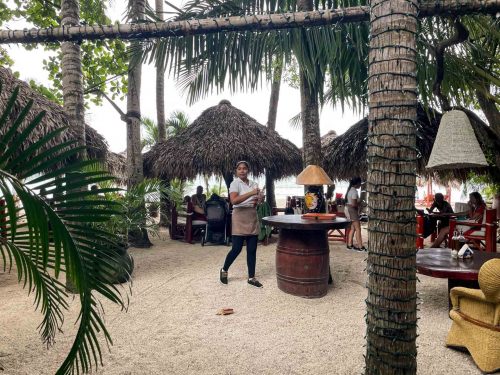

Beaches like Puerto Carrillo and Sámara (photographed here) bear witness to pick up soccer games at carcinogenic times of day, and strips of meat and cans of beer, birthday cakes, tortillas and loud music and more cans of beer. Some 83 percent of national tourists prefer to take their own, prepared food. The concrete promenades full to the brim confirm this.

The long-awaited and spontaneous year-end vacations are a safari of our own identity where we can see, without binoculars, the family rituals of our neighbors that distinguish us, but that also make us similar.

“We made dug a pool but the water never came,” says 12-year-old Adán Steve Sequeira, who traveled with is family from Maquenco in Belén de Nosarita in order to inaugurate the end of the classes.Photo: César Arroyo

The men of the Campos Pérez family waited for the tide to go out at Sámara beach before playing soccer under the brutal 3 p. m. sun.Photo: César Arroyo

José Alberto Barrantes made a roasted sausage and watched the sunset with his family.Photo: César Arroyo

Edith Gómez of Santa Marta, Hojancha cuts her 11th birthday cake to share with her parents, uncles and aunts, cousins and siblings in Puerto Carrillo.Photo: César Arroyo

During afternoon naps in Puerto Carrillo, hammocks, sheets and pillows are seen under the shade of palm trees alongside the highway.Photo: César Arroyo

Comments