Liberia’s Tope de Toros (bull parade) event can easily transport you back to the 19th century. The town still preserves the old adobe and bahareque houses, people dress completely in white as in the old cattle ranches, and a stampede of oxen and horses advance down the middle of the street with marimbas as background music.

This tradition was declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Costa Rica in 2013. There are so many reasons why the parade is kept alive that researcher María Soledad Hernández reviewed documents from three centuries to explain how the tradition evolved: what has changed and what remains intact.

Some want to demolish it and build another in its place. For others, this bridge represents Liberia’s identity.

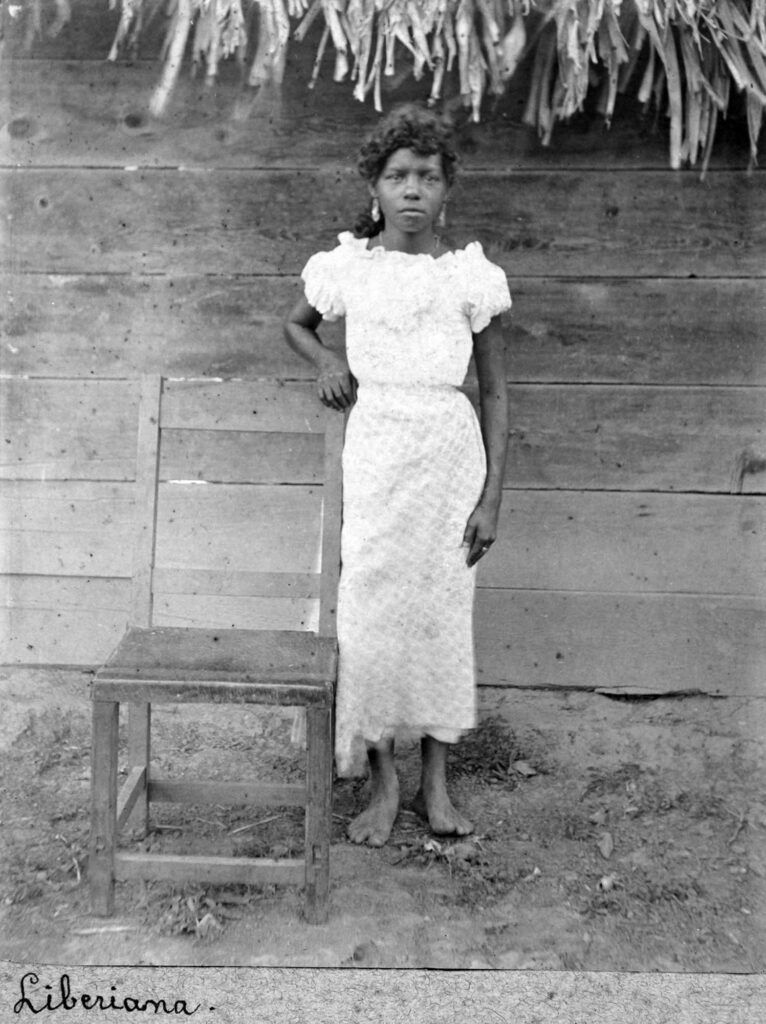

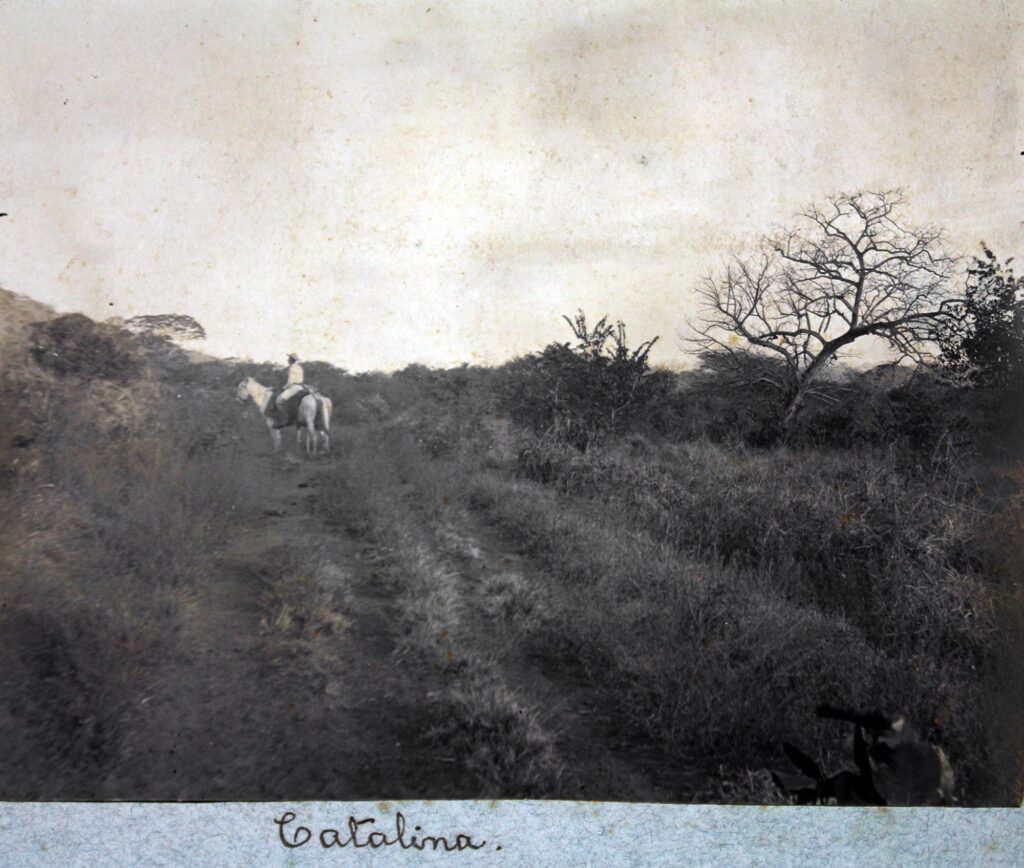

The book is called Resignificaciones históricas, voces de la memoria (S. XIX-XXI) (Historical Redefinitions, Voices of Memory), and you can download it for free here (Spanish only). Hernández shared with The Voice of Guanacaste five images that represent five episodes of the tradition.

1. From the Elite to the Common People

During the colonial era, bull festivities were a symbol of social prestige, which could only be enjoyed by the powerful classes. The political and religious elite regulated and censored the indigenous, black and mulatto people from this type of activity. But slowly, the mestizo groups were appropriating that “Spanish” custom.

During the colonial era, bull festivities were a symbol of social prestige, which could only be enjoyed by the powerful classes. The political and religious elite regulated and censored the indigenous, black and mulatto people from this type of activity. But slowly, the mestizo groups were appropriating that “Spanish” custom.

Many free blacks and mulattoes stood out due to their great skills as cowboys, to the point that the 16th century laws that prohibited them from riding horses or using weapons were almost always ignored because their skills were necessary.

All the knowledge accumulated through the centuries during the colonial era created the conditions to confront this historical exclusion and the communities were filling these cattle festivities with local identity.

2. The New Capital

Before the arrival of the Spanish and during the first centuries of the colonial era, Nicoya was the center of political and economic power in Guanacaste. Until cattle ranching became the province’s main economic activity and haciendas (ranches) began to be established in the north of the province. Why did it happen?

Before the arrival of the Spanish and during the first centuries of the colonial era, Nicoya was the center of political and economic power in Guanacaste. Until cattle ranching became the province’s main economic activity and haciendas (ranches) began to be established in the north of the province. Why did it happen?

Some of the reasons were the distance and the difficulties caused by travel between Nicoya and Nicaragua, the extinction of indigenous people in this region, and the fact that Liberia had better geographical conditions, both for caravans to pass through with cattle and for settling haciendas.

In addition, the Nicaraguan elite’s interest in expanding their estates to the south during the 18th century made Liberia, formerly known as “El Guanacaste,” more and more important in the region.

3. The Country School

The responsibilities of the sabaneros (plainsmen) involved gaining enough trust from the hacienda landowner to work without much supervision and to have the necessary skills for the hacienda’s success.

The responsibilities of the sabaneros (plainsmen) involved gaining enough trust from the hacienda landowner to work without much supervision and to have the necessary skills for the hacienda’s success.

Their role was so important that the salary on Guanacaste’s haciendas reached a point of being higher than that of workers in the Central Valley (between 0.75 and 2 colones per day on the haciendas and between 0.50 and 1.28 in the Central Valley). This changed drastically after the 1940s, when Guanacaste shifted its production style towards foreign investment and export agriculture.

Hernández thinks that the sabanero came to represent more and more the people, humility, simplicity and learning from everyday life.

“It’s a decolonial turn to allow us to think that knowledge is not just where we think it is, in the universities, but also that learning can come from very humble and simple people,” explained the researcher.

4. Landowners and Protagonists

For many years, the Tope de Toros was an activity mainly for men. Due to the danger, children and women saw it from inside their houses, since previously they rounded up fierce and wild bulls (which had grown up naturally in the countryside, without human intervention).

For many years, the Tope de Toros was an activity mainly for men. Due to the danger, children and women saw it from inside their houses, since previously they rounded up fierce and wild bulls (which had grown up naturally in the countryside, without human intervention).

“The value of including people and groups that were perhaps a little marginalized before has been reinvented and redefined,” added the researcher.

But women weren’t just spectators in Liberia’s bull tradition. The book also lists the names of the haciendas with their respective owners. The list includes Rosa Claudia Espinoza, who was the owner of the Santa Rosa Hacienda in the year 1797.

5. Oral Tradition

The oldest documentation that mentions the Tope de Toros that the researcher found dates from 1877. Even so, it’s possible that this tradition is even older but that it hadn’t been documented on paper.

The oldest documentation that mentions the Tope de Toros that the researcher found dates from 1877. Even so, it’s possible that this tradition is even older but that it hadn’t been documented on paper.

“When I make the comparison between how the tope was celebrated in the 19th century and how it is celebrated today, I find many similar things. That can only mean that the oral tradition was very faithful over time,” concluded Hernández.

During the colonial era, bull festivities were a symbol of social prestige, which could only be enjoyed by the powerful classes.

During the colonial era, bull festivities were a symbol of social prestige, which could only be enjoyed by the powerful classes.  Before the arrival of the Spanish and during the first centuries of the colonial era,

Before the arrival of the Spanish and during the first centuries of the colonial era,  The responsibilities of the sabaneros (plainsmen) involved gaining enough trust from the hacienda landowner to work without much supervision and to have the necessary skills for the hacienda’s success.

The responsibilities of the sabaneros (plainsmen) involved gaining enough trust from the hacienda landowner to work without much supervision and to have the necessary skills for the hacienda’s success. For many years,

For many years,  The oldest documentation that mentions the Tope de Toros that the researcher found dates from 1877. Even so,

The oldest documentation that mentions the Tope de Toros that the researcher found dates from 1877. Even so,

Comments