The preliminary election results give us insight that Guanacaste is the coastal province with the fastest growth in abstentionism between the 2014 and 2022 elections. It went from 37% in 2014 to 48% in 2022, an increase of 11 percentage points.

In the same period, the province with the least growth in the country was Limon, which increased by seven percentage points. There, abstentionism was already 41% since 2014 and in these elections, it reached 49%.

Both of these provinces and Puntarenas are the ones that recorded the highest rates of abstentionism in national elections. The problem is exacerbated in border cantons such as La Cruz (58%) and Corredores (55%), along with Golfito (57%), Garabito (55%) and Talamanca (54%).

This isn’t strange, according to political scientist Gustavo Araya. He explained that “in Costa Rica, there is a correlation between electoral participation and the human development index (HDI),” a calculation that measures life expectancy, schooling and material well-being. The lower the index, the higher the abstentionism.

How did the presence of political parties in the province affect matters? What coincidences do the regions outside the Greater Metropolitan Area have in common? We spoke with political scientists Eugenia Aguirre and Gustavo Araya to understand the results of the first round in Guanacaste in three points:

1. Growing abstentionism

If we look at the first rounds of the last two election periods (2014-2018 and 2018-2022), Guanacaste is the coastal province with the highest growth in abstentionism, ranking second nationwide, just below Alajuela.

People who don’t vote feel that their vote isn’t going to accomplish anything anyway,” explained analyst Gustavo Araya.

In addition, Guanacaste reported the canton with the most abstentionism in the entire country in these elections. That’s La Cruz, at 58%. Other border cantons follow: Golfito (57%), Corredores (55%), Garabito (55%) and Talamanca.

Talamanca, Los Chiles and La Cruz have been among the five cantons with the lowest HDI in at least the last three editions of the index.

Can coastal voter participation recover? According to Araya, “only if the development model takes them into account and the infrastructure, education, health, employment and everything else begins to have the same conditions as those in the central plateau.”

The mayor of La Cruz, Alonso Alan, feels that the reasons for abstentionism have to do with abandonment. “The hope and expectation of feeling represented by exercising the vote in national elections has been dissipating,” he wrote on his Facebook page. “State centralism has us forgotten and in misery.”

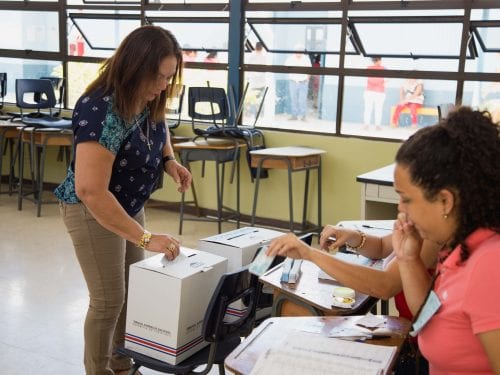

An Public Force officer votes at Salvador Villar School in La Cruz, the canton that reported the highest percentage of abstentionism in the country, according to preliminary results from the Supreme Electoral Court (TSE- Tribunal Supremo de Elecciones). Photo: The Voice of Guanacaste

2. New Republic as a political force

Fabricio Alvarado, from the New Republic (NR) party, was the candidate who received the most support from the electorate of Limon and Puntarenas. In Guanacaste, he was positioned as the second political force, after Jose Maria Figueres from the National Liberation party (PLN for the Spanish acronym).

This shows that the vote on the coasts behaved differently than in the provinces in the center of the country (Cartago, San Jose, Alajuela and Heredia) where the two candidates to receive the most votes were the ones who advanced to the second round: Figueres and Rodrigo Chaves, of the Social Democratic Progress Party (PPSD for the Spanish acronym).

In the last two elections, Guanacaste, Puntarenas and Limon have opted for political options that aren’t the winners,” explained Aguirre, a researcher at the National Political Observatory.

“We’re talking about populations that not only abstain in a very important way, but when they vote, their options aren’t necessarily the ones that transcend,” she added.

Why did the coastal provinces choose Alvarado? Analysts sum it up in three reasons: Alvarado is the visible face of a religious political movement, the party achieved an important representation of the coasts in the current Assembly (2018-2022) and retained that public in the recent electoral campaign.

Alvarado is the candidate who accumulated the largest number of voters with a significant religious tendency. “In the absence of the State and of public policies, the religious organizations [represented by Alvarado and his party] have come to fill that void in terms of development needs,” explained analyst Eugenia Aguirre.

Their discourse on family values led the party to take 14 candidates to the Legislative Assembly in the last elections, six of them representatives of the coastal provinces: three from Limon, two from Puntarenas and one from Guanacaste.

“[The New Republic party] divided, but Fabricio Alvarado remained the representative of that failed attempt from the coasts to shout in an electoral process,” pointed out Araya.

According to the analyst, Fabricio Alvarado managed to retain those voters from 2018 in this campaign also. “The dry channel proposal involving the coastal provinces was not in vain. Fabricio Alvarado continued to speak to his own audiences, only now just not with the hegemony that he had before on the subject of religion,” he said.

An analysis by political scientist Elias Chavarria shows that in 2018, a lower HDI was also linked to greater support for Fabricio Alvarado when he participated representing National Restoration.

A group of people who support Fabricio Alvarado and the New Republic Party (PNR), outside Leonidas Briceño School in Nicoya. In the coastal provinces, voters gave their support for the presidency to Alvarado and to Jose Maria Figueres (PLN). Photo: Cesar Arroyo Castro

3. PUSC recovering slightly

According to preliminary results, the Christian Social Unity Party will fill two of the province’s seats, a representation that hasn’t happened since the 2002-2006 term.

In fact, Guanacaste and Limon are the provinces where PUSC increased the percentage of support on both the presidential and legislative ballots compared to the 2018 elections. Cartago also increased its support for this party but only on the presidential ballot.

In the three provinces, the Social Christians gained one more legislative representative compared to the current makeup of the Legislative Assembly.

PUSC’s recovery isn’t seen in the national percentage or in the other four provinces, where support decreased instead and they maintained the same number or even lost legislative seats.

Analyst Aguirre believes that, to some extent, the Social Christians maintain a level of experience and political machinery similar to that of PLN.

And there’s also the issue of territorial roots,” she added. “They have a tough vote that continues to respond to a call for elections. In fact, many of the mayor’s offices that they have are from rural areas.”

In Guanacaste, PUSC currently leads the mayor’s offices of Liberia and Bagaces.

“I see it as a limited response. That is to say, they have an important legislative advance, but they stay there. In the presidential sphere, they don’t manage to transcend and they have been out of power for 20 years now,” Aguirre pointed out.

To her colleague, Araya, another reason is Linneth Saborio’s political proposal. “Saborio laid out a much less liberal campaign and more of a reconstruction of the Costa Rican socio-political fabric. She was a less repellent version of what Rodolfo Piza could turn out to be.”

Comments