The bars of a marimba resonate in the air, accompanied by the echo of a quijongo (an indigenous string instrument). A woman with chocolate skin, wide hips and curly hair taps her feet and kicks up dust from the ground of her province, which was also home to her parents and her grandparents.

Anyone who has danced to parrandera music in their town’s streets is probably familiar with such a Guanacastecan image. That scene would not exist without the black people who came as slaves to these lands five centuries ago.

Guanacaste was the first place where people of African descent set foot in Costa Rica, years before they arrived in Limon. However, this episode isn’t mentioned much in the province’s interwoven history.

How did this population group arrive in the province, and what do we know about them? To understand it better, The Voice compiled explanations that professor and researcher Elizeth Payne, genealogist Mauricio Meelendez and researcher and university professor Rina Caceres had given to this medium.

Roots that Reach Back Five Centuries

The Gulf of Nicoya was the gateway for the Spanish conquistadors in 1524, as well as for the enslaved African people who accompanied them.

Elizeth Payne, a professor at the School of History and researcher at the Central American Historical Research Center, explained that they arrived in small numbers as helpers of the Spanish.

The area of Nicoya and Guanacaste was conquered very early, unlike the Caribbean. We aren’t going to have any population there [in the Caribbean] until 1632, already very late. Without a doubt, these first enslaved blacks arrived in the Pacific,” she affirmed.

It’s not clear how many black people arrived with the Spaniards or where they came from originally. Researcher Rina Caceres believes that the majority could have come from what is now known as Congo and Angola since many words that we use in Guanacaste contain “mb” or “ng,” such as mondongo (tripe), marimba (instrument similar to a xylophone) or panga (a fishing boat). This reveals a Bantu influence, which is a set of languages spoken in Africa.

The main reason that we don’t have information today about these first migrations is due to two fires that destroyed the oldest documents in Nicoya. One of them occurred in the government building of Nicoya in the year 1767 and caused all the documents in the mayor’s office to be lost.

The other fire, in 1783 in Nicoya’s rectory or parish house, destroyed all of the sacramental documents, such as baptism and marriage certificates.

“Imagine that Nicoya began to function for the Spanish crown in 1524, and in 1767, everything there was burned. So we fell short of being able to explain in detail everything that happened in Nicoya during more than 200 years,” pointed out genealogist Mauricio Melendez.

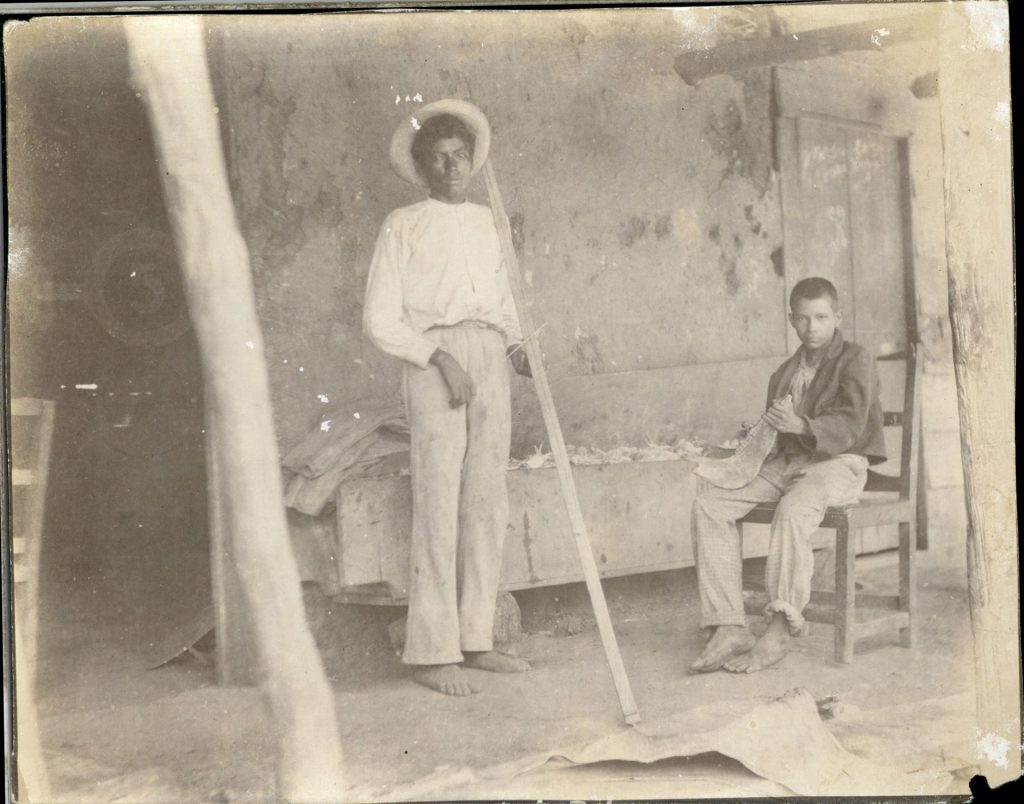

Young people from Hacienda Catalina. Guanacaste. Date: 1904.Photo: National Archives of Costa Rica

Melendez is also the president of the Costa Rican Academy of Genealogical Sciences, and he worked on the publication of an academic magazine called El origen de los guanacastecos: la familia Viales y los firmantes del acta de anexión (The origin of the Guanacastecans: The Viales family and those who signed the annexation act), which explains who our ancestors were.

The publication shows that the African roots in Guanacaste are much broader than many imagine.

The oldest Afro-Mestizos possibly come from the 16th century. I don’t think it was a high population, but it was large enough to impact offspring for several centuries,” added Melendez.

Iberian Soul and Chorotega Courage… and the Black Heritage?

Melendez’s research reviewed 2,792 baptisms in Nicoya from 1783 to 1804 and determined that 73.5% of those baptized were mulattos. Although mulattoes are generally people of black and white descent, in this case, they used this word to refer to the zambos: a mixture of an indigenous person with a black person. Melendez compared documents from people who were sometimes categorized as zambos but were later cited as mulattoes.

The remaining percentages were 20% indigenous, 1.8% zambos, 1.1% Spaniards, 0.3% mestizos (Spanish and indigenous) and 3.7% had no category, which means the priest didn’t record a socio-racial categorization for them.

“That’s where the myth falls apart. There’s no such [evidence] that the majority of the population was Indian. In the case of Guanacaste, the emphasis on the people being Chorotegas is always emphasized, which is undeniable, but the Afro-Mestizo roots are always systematically forgotten,” Melendez pointed out.

The Voice of Guanacaste spoke with philologist and genealogist Mauricio Melendez to understand what was happening 200 years ago in the province that we now know as Guanacaste.

The reduced population of 20% indigenous people that appears in the documents from the colonial era is the result of the depopulation that the indigenous people suffered at the beginning of the conquest.

The article Los indígenas de Nicoya bajo el dominio español (The indigenous people of Nicoya under Spanish rule), by historian Luis Fernando Sibaja, points out that 10 years after the first incursion of the Spanish into the Gulf of Nicoya, in 1529, the indigenous population was reduced by 82%.

Upon reaching the Gulf of Nicoya, the Spanish found societies with a highly developed economy, not only on the mainland but also on the islands. The Island of Chira was the most important of them because it had the main port in the area. There, the conquistadors took enslaved indigenous people, sold them, and sent them on ships to Panama and Peru.

They also died from famines and diseases that plagued them, and because they were in the hands of networks of economic and political power, such as Pedrarias Davida and his descendants. They distributed indigenous people to their friends and relatives.

Even with the drastic reduction in the Chorotega population, during the following centuries, Nicoya continued to be made up of indigenous towns. Ladinos (a general term for anyone who wasn’t indigenous: mulatto, mestizo, or Spanish) could not live in these towns.

That’s how Afro-Mestizos who couldn’t live in Nicoya began to found other towns such as Santa Cruz or Liberia, where they established small cattle ranches.

These Afro-Mestizos had been turning into ranchers and were growing. It turned out that by 1790, their haciendas already competed with the ones in Rivas sometimes in number of cattle,” added the genealogist.

These families of African descent began to be more powerful and finally had a determining role in the direction that the Nicoya Party would take when it joined Costa Rica in 1824.

“We are heirs to civilizations that go beyond 1821, and that’s why it’s important to raise awareness about it and break the myths that tarnish the memory of our peoples,” emphasized researcher Rina Caceres.

Comments