In these times of drought, wasting water is not an option, especially in light of the estimates that in 2016 Guanacaste will continue to have a rain deficit, similar to this year.

Due to that fact, the Nicoya Health Area and the Social Studies in Population Institute (IDESPO – Instituto de Estudios Sociales en Poblacion) of the National University (UNA – Universidad Nacional) reached an agreement to provide financing, training and construction oversight of wetland wastewater treatment system in the canton of Nicoya.

Biogardens, or horizontal wetlands, are systems that use aquatic plants for the treatment of greywater, principally sources that come from the house, although they can also be used in larger projects such as neighborhoods, industry and hotels.

Mario William Acosta, coordinator of the wetlands program for the Ministry of Health, reported that since 2013 the systems have been used in the Nicoyan community of Hondores. In that case, UNA launched a pilot project at the home of the Jimenez Lopez family, who still benefit from the water savings.

Maria Gregoria Lopez Castrillo feels satisfied with the results they’ve had from adopting the wetlands in their home, which hosts four people. “It has gone very well; before the water bill was about ¢4,500 ($8.50) and now it costs some ¢3,200 ($6.00) and we use the water from the wetlands in the rainy season for cleaning and in summer to water plants,” she explained.

According to Maritza Marin, who is in charge of the wetlands project for the Central American Association for the Economy, Health and Environment (ACEPESA – Asociacion Centroamericana para la Economia, la Salud y el Ambiente), the biogarden needs to be functioning for some six months to reach optimal performance.

In addition, she indicated that on average a person uses about 250 liters of water per day, and with the wetlands, the water savings could be 30% monthly.

According to Marin’s estimates, the savings on the monthly bill for a family of four members would be about¢900 ($1.70) per bill.

Mario William Acosta indicated that the installation of those systems is of fundamental importance, above all during times of water scarcity. In addition, he believes that their use can prevent nurseries for mosquitos because they do not produce the residual water that is normally lost or emptied onto the house’s yard, where it can remain stagnant.

“People are wasting a lot of water. In these times of drought, wetlands are an excellent option for those who want to save water,” indicated Acosta.

Additionally, a wetlands will be built in the community of Barra Honda in Nicoya in October, and the construction of two more in that community and in Nandayure is also planned.

Project to Clean Polluted Creek Water

One interesting thing is that wetlands do not just treat greywater from homes, but they can also clean polluted water in creeks.

Ericka Campos, president of the Hojancha Development Association, reported that it is planned to build a communal wetlands to renew the waters of Elena Creek, located in the canton’s urban center.

According to Campos, the project is in the initial study phase and it won’t be until 2016 that they hope to implement it, when the costs, designs and details for the plan have been defined.

Regarding the biogarden’s maintenance, Acosta explained that it is necessary to remove grease and solid waste every week, which can be used for compost.

How does a wetlands Work?

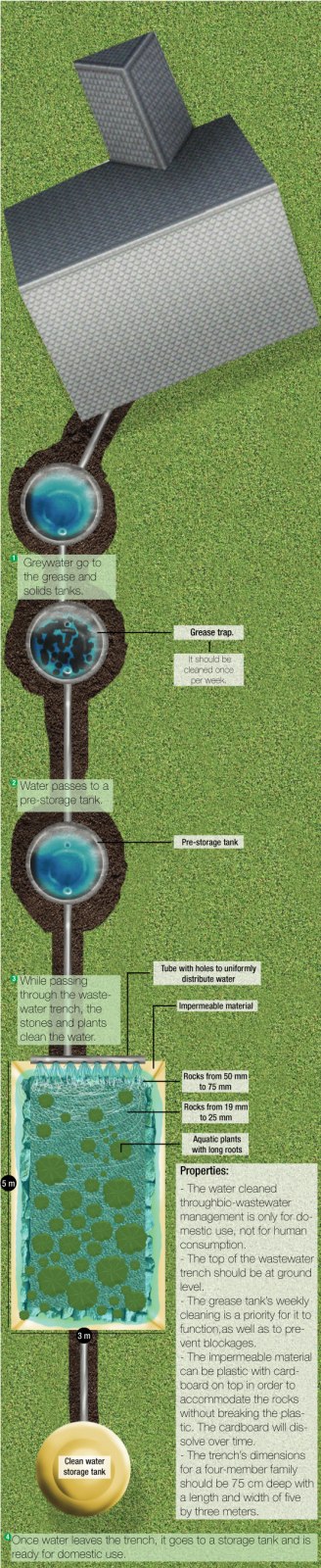

For a wetlands to work, a hole of 75 centimeters in depth should be dug and coated in an impermeable material so that water can’t leave it. It can be built with materials including concrete, reinforced concrete, blocks or bricks.

In that way, the water coming from sinks, showers in bathrooms, the kitchen and from the clothes washer arrive by gravity to the first receptacle or grease trap. There, the biggest residues are trapped in a fine screen, after which the water goes into the biofilter, where long-rooted swamp plants are installed among limestone rocks. The filtering process is finished, as residues remain trapped among rocks and are absorbed by the plants’ roots.

Finally, the leftover water, although unfit for human consumption, is deposited in a tank for a variety of uses including watering gardens, cleaning yards, washing cards or even to cultivate fish.

A variety of dimensions can work, according to the size of the family, and go from five meters long by 75 cm to 10 meters by 75 cm.

The approximate cost for a wetlands is about ¢350,000 ($660).

Comments