Enid Ruiz points to three buckets filled with rainwater, which she will use to bathe and wash her family’s clothes. Water doesn’t always reach it here in Playa Hermosa: Sometimes it comes on water trucks, while other days it doesn’t.

One kilometer from the village of Hermosa, Arellys Vallejos opens the tap and salty, brown water comes out, from the Mercedes aqueduct in Playa Panamá. She says that some neighbors – like her – have a well to meet their needs when water comes out like this. Others have tanks to store it. But those who are worse off have only bottles to “get by.”

“I travel in a pickup to collect barrels of water for the entire week at my in-laws’ home in El Coco,” said Arellys’ cousin Fabiola Vallejos.

A well belonging to Arellys Vallejos (pictured here) supplies water to her father and the family of her neighbor, Belkys Vallejos, because tap water is salinized or dirty.

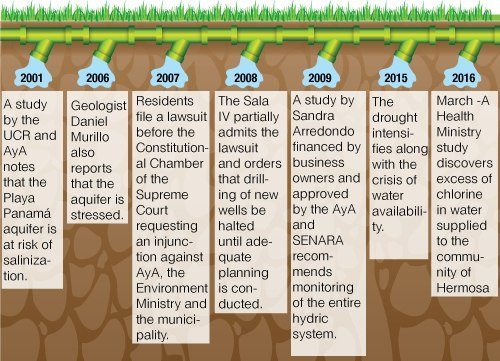

Despite 15 years of warnings and recommendations from specialists and residents to avert this crisis, this year has witnessed what all hydrogeologists have feared in their studies on the Playa Panamá aquifer, which provides water to the community of Hermosa: The amount of freshwater has diminished and saltwater has invaded.

At least three studies have warned of the aquifer’s vulnerability since 2001, and since then, four administrations have known of the consequences without resolving the problem, the aquifer’s vulnerability.

Of nine wells where water is extracted for both communities, three are completely inoperable due to salinization, and the others are only partially operable with some water already salinized, according to German Araya, Guanacaste’s regional director of the Costa Rican Water and Sewer Institute, or AyA.

Today, the community of Hermosa is supplied by the Mercedes well at a capacity of only 4.5 liters per second, a rate that has diminished from 17 liters per second. Salinized water also reaches the hotels, which treat it themselves, Araya said. The problem affects the primary economic activity for many Hermosa residents (in the district of Sardinal), where 3,000 people live, according to community leaders.

“My husband and her husband went to look for work in San Carlos, because they used to work in tourism, and they don’t know with the current situation if they’ll find something to do,” Arellys Vallejos said.

Vallejos and her neighbors wonder how they arrived at this extreme situation, after having been warned for many years.

AyA has promised to install a desalination plant to treat well water, and they say work will begin in December.

But two decrees must first be approved – stalling the process – that would permit AyA to utilize salinized aquifers in cases of emergency, such as the current one.

[video:https://youtu.be/TCSjHKNjCb8 width:500 align:center autoplay:0]The Studies

Water researchers grew concerned about the Playa Panamá aquifer at least 15 years ago. One of the first studies of this century to mention the problem dates to 2001 and was carried out by the University of Costa Rica’s School of Geology and AyA.

“Some of the aquifers that are threatened by salinization and over-exploitation are Panamá, Hermosa, Coco, Potrero, Brasilito and Jicaral beaches,” the study noted.

Five years later, in 2006, Costa Rican geologist Daniel Murillo conducted research with AyA for his master’s thesis at the Curitiba de Brasil University on the maximum limits of consumption and the danger that would occur if pressure on the aquifer continued and ocean water invaded.

The researcher acknowledged in an interview with The Voice of Guanacaste that the study did not show the entire reality of the aquifer because he could not access private wells, and after publishing the results, it was criticized by business owners who claimed a larger hydric capacity at the aquifer.

Partly due to these warnings, in 2009, hydrogeologist Sandra Arredondo, hired by tourism business owners in the region, conducted a study to determine the availability of subterranean water.

The study yet again noted the aquifer’s vulnerability and concluded that salinization had not yet occurred, but a monitoring plan was urgently needed to prevent this risk, as well as the installation of flow meters at the exit point of wells to verify how much water was extracted from them and to ensure compliance with concessions.

The National Groundwater, Irrigation and Drainage Service (SENARA) and AyA studied the results of this latest study and began to take periodical measurements with some regularity.

“Sometimes there weren’t travel allowances, other times officials were incapacitated, or other times there was no transportation available,” Arredondo said.

With this compiled information, beginning with Arredondo’s study, AyA noted that water volume had diminished, AyA regional director Germán Araya said, and the agency began to take certain steps including reducing the production of water from the aquifer and halting the availability of water for large projects.

Nevertheless, they never installed flow meters at the exit points of wells under concession to private businesses, such as at the Condovac hotel.

“That’s the responsibility of other agencies; we can’t do it,” Araya said.

That has prevented officials from determining with precision how much water was being extracted from the aquifer.

Residents Up in Arms

Not only experts were worried. In 2007, Enid Ruiz and 85 other residents filed a lawsuit before the Constitutional Chamber of the Supreme Court, or Sala IV, requesting an injunction, claiming that there was no guarantee the aquifer could supply water to the communities after several real estate projects were slated to be built in the region.

The Sala IV partially admitted the lawsuit in 2008, arguing that AyA continued to grant water use permits without actually knowing how much water was in the aquifer, threatening the right of residents to access water.

“It is ordered that the perforation of new wells in these aquifers be halted until hydric planning is conducted to facilitate adequate projections, in order to avoid over-exploitation of the water tables,” the court ruled. The AyA has assured that since then, it has not issued water use permits for large projects, only for vegetative growth.

The communities reacted in time, but the consequences are the same today as if they had done nothing. Not only did they lose access to potable water, but also many properties have lost considerable value.

“The properties have been devalued. If one day we want to leave, we’re never going to be able to sell our properties,” Enid Ruiz said.

Why Didn’t Informed Agencies Prevent This?

The AyA argues that a three-year drought has wiped out the water supply.

“When the phenomenon (of drought) started in this region, it began very slowly, but the salinization process happened quickly in a short period. From June (2016) to now we’ve had to take several wells out of operation,” AyA Deputy Director General Manuel Salas said in a telephone interview.

Is that an acceptable explanation? Andrea Suárez, coordinator of the National University’s Center for Hydric Resources for Central America and the Caribbean, said drought is only one of the factors.

“(This) is the result of a lack of planning, of an understanding of the sources, of the organization of concession issues, of not knowing how much is being extracted from the wells,” Suárez said, referring to the problem of Guanacaste in general.

AyA Executive President Yamileth Astorga agrees that poor planning has forced the country not only to use sources improperly, but also to obtain water from sources that shouldn’t be used in the first place.

“What has happened is that the coastal aquifers should never have been used,” Astorga said.

Today, the same residents who have called for the protection of aquifers are the ones who receive dirty, salinized and overly chlorinated water.

Comments