Danixa Matarrita felt that her water broke. It was 1 a.m. on a Monday and she was 39 weeks along. Although it was her second pregnancy, this was the first time she felt what it was like to have her water break. She immediately called her doula, who calmed her down. And she also wrote to her midwife, an obstetric nurse who would be with her through the delivery.

She had decided to give birth at home because she wanted a different experience from the one she had with her first child, Luciano, who was born in 2019. That time, she felt that everything happened as if by pure inertia, almost like an administrative procedure and not like an experience. “I didn’t know anything and I trusted my doctor 100%,” she recalled.

Luciano’s delivery happened in a private hospital in Guanacaste. She remembers that the doctor told her that a cesarean would be best because her baby was big and that, in any case, it was the only thing the hospital offered “because they didn’t have the availability to wait until the baby decided to be born,” related Danixa.

Like Danixa, women in Guanacaste and throughout the country have more and more tools to decide how, where and with whom they give birth. And in that framework of decisions, they opt for synergy between women. Between doulas and obstetric nurses, they have respected deliveries and better pregnancies.

Doulas physically, emotionally and educationally support women in the maternity processes, from pregnancy to postpartum, regardless of whether they give birth at home or in a medical center.

In Costa Rica, doulas are independently certified with the national association Mamasol or with the Doulas of North America (DONA) organization. The Costa Rican State still doesn’t recognize this figure.

According to data compiled by the American Pregnancy Association, doulas can help reduce C-section rates by 50%, labor length by 25%, and the need for epidurals by 60%. In addition, they provide support to minimize the mother’s stress and increase her satisfaction with the birthing process.

In fact, some health systems have included them in programs to reduce infant mortality in at-risk populations, such as women living in poverty, with physical or emotional trauma, or with drug addiction.

Those who practice as midwives are registered obstetric nurses. They help women deliver babies at home. Although there are several in Costa Rica, in Guanacaste, there aren’t any that provide the service, as confirmed by all of the people interviewed for this report.

Empirical midwives stopped practicing between the late 1990s and early 2000s, except in some cases in indigenous territories. This was asserted in 2016 by the then coordinator of the National Commission on Maternal and Child Mortality of the Ministry of Health. In an article in the newspaper La Nación, he explained that they were no longer authorized to attend to births after training in which they understood the risks of doing so.

According to the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (Spanish acronym: INEC), in 2021, 418 babies were born at home (26 of them in Guanacaste). That doesn’t mean that all of those pregnant women decided to do so; for some, it was an emergency or they gave birth while they were on their way to the hospital.

Deciding

Those who decide to give birth at home don’t necessarily do so in the province. Danixa and other women had to go to the Greater Metropolitan Area, where obstetric nurses take care of home deliveries, a few days before the expected delivery date.

This was also done by Flaminia Calabresi and Melina Chacón, residents of Nosara and Monteverde, from Puntarenas, who also told their stories to The Voice. Both decided to give birth at home to ensure that the natural cycles of their bodies were respected, to be in peaceful environments or accompanied by their doulas. After their deliveries, they also decided to study to become certified as doulas.

“For years, I said: when I’m going to give birth, I’ll give birth at home. Knowing women doulas, midwives and doctors made me recognize and remember the importance of feeling comfortable when giving birth,” said Melina. “My doctor from EBAIS always supported me. And that was something very nice. I felt calm to be able to communicate this in a public health service center.”

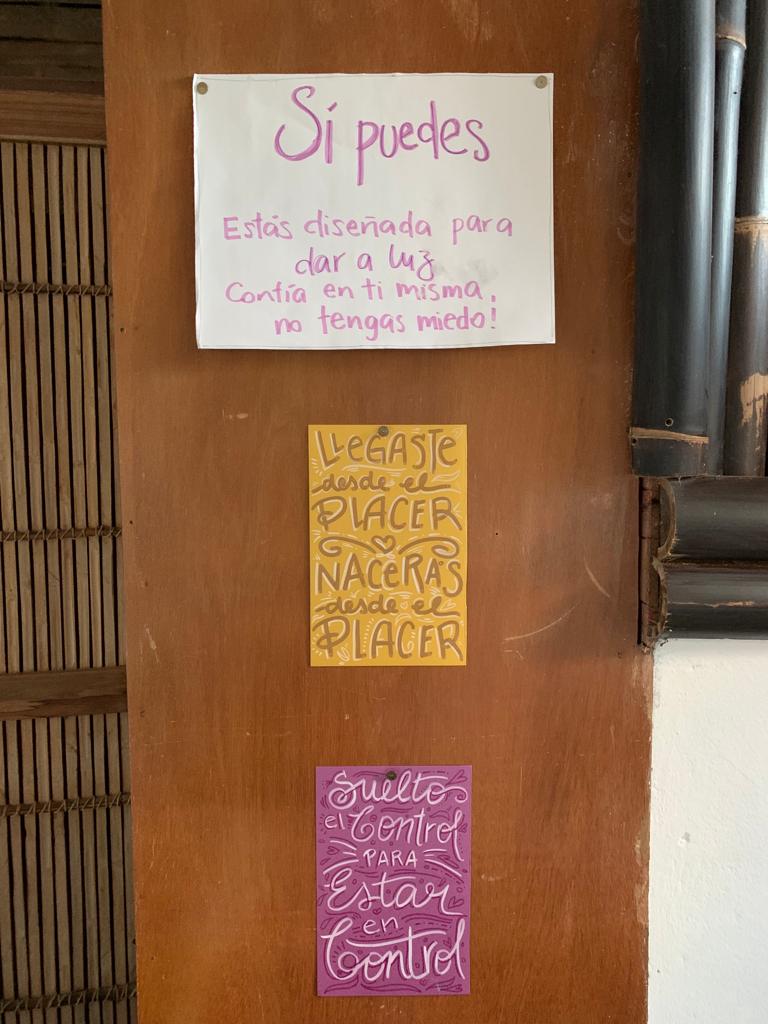

Melina Chacón asked her family and friends to make messages for her to read before, during and after the birth. She hung them around the house where she gave birth. Photo: Courtesy of Melina Chacón

Not everyone has that luck. Home births are not regulated in any way in the country, as is the case in countries like the Netherlands, where the public health system promotes home births for pregnant women.

For many, it’s not about going against the public health system, but rather about having the power to choose: home or hospital, vaginal delivery or C-section. Whatever the woman wants, with the support of specialists, to give birth.

“I always believed that having a home birth was the best, with the precautions that must be taken and at no time am I against medicine. [Medicine] seems spectacular to me, incredible, only sometimes it gets out of hand and the human aspect is lost,” said Flaminia.

In two months, Flaminia will have her second child, and she has planned the same process: a home birth with her doula and the obstetric nurse.

The only thing different is that I have a three and a half year old who is going to be there and participate as he pleases,” she said with enthusiasm.

The country doesn’t have a law that prohibits out-of-hospital deliveries. However, the College of Physicians did rule against it, in 2017, when a woman died after giving birth at home under the alleged care of an obstetric nurse who had not graduated or joined the college.

A System that Protects Them

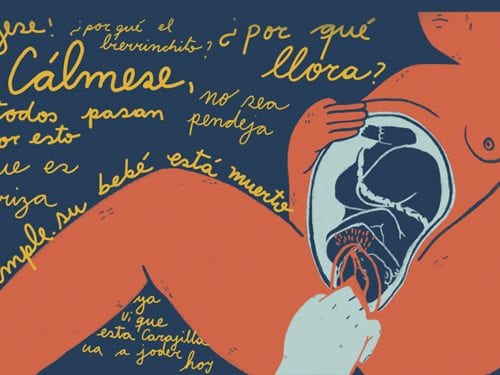

Like Flaminia, many women fear experiencing obstetric violence in medical centers. This term refers to the violence experienced by women before, during or after childbirth. For example, not being able to choose in which position to give birth, not being informed or not being asked for consent about the procedures that are performed, being yelled at or insulted.

Faced with complaints of disrespect in the health system, the government has taken steps to increasingly guarantee humane treatment. That’s why women who give birth in hospitals now have greater support to experience a safe delivery.

In 2019, the country approved a respected childbirth law that institutionalized eight rights for women, such as receiving information about each procedure, giving birth naturally when there is no risk, and having skin-to-skin contact to bond.

Women of the province needed psychological attention after experiencing obstetric violence during pregnancy.

This is in addition to the comprehensive care guide, which puts together guidelines so that medical professionals know how to act. There is also the birth plan, a route designed by each woman in which she indicates who will be present with her, in what position she will give birth, and whether or not she wants analgesics during her delivery (see an example of a birth plan on page 105 of this document).

The Voice consulted Dr. Ileana Quirós about the rules, who led the processes within the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS) in preparing it and was coordinator of the Women’s Care Program.

“We made an effort for scientific evidence and humanization to prevail,” she said. This evidence is compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its recommendations. Among those recommendations are: not using oxytocin to speed up labor, adopting the desired position to give birth and avoiding an epistomy. “The WHO says that there has to be a valid reason to interfere in the process, which is physiological,” she remarked.

That’s why, for her, the discussion about births should not be about whether or not they take place at home, but rather how women are cared for wherever they give birth.

The issue of home birth is not that it’s dangerous,” believes Quirós. “Wherever it is, it has to meet standards, with people who are 100% trained.”

“Now, what is it that they’ve been trying to do? To have women give birth in the hospital as if she were at home, but it’s very difficult due to the conditions,” she added.

One activist for respected childbirth in Costa Rica is Rebecca Turecky, who has a master’s degree in obstetric and midwife nursing, is co-founder of Mamasol, a defender of the humanized childbirth law, and co-creator of the doula certification program. To her, the advances have been key but are not enough because although the protocols exist, in practice, they aren’t applied in all medical centers. The changes must go further, she believes.

“The change isn’t only in CCSS, nor in the protocols nor in the personnel. They need to change, but we need to work more with women and families,” she said.

Due to the pandemic, Mamasol began to provide doula certification online. In that way, women like Zarelly Canales, a resident of Liberia and a physical therapist, were able to get trained as doulas.

“Many women, not just from Costa Rica, were waiting for that opportunity to open up,” she said. Both she and Turecky acknowledge that there are myths surrounding the role of doulas, such as caring for births. But their code of ethics is clear: they support the women but never suggest medical procedures, much less apply them.

Obstetric nurse Rebecca Trecky monitors a woman’s pregnancy. According to her records, she has cared for around 1,000 home births, the vast majority in Costa Rica. Photo: Courtesy of Rebecca Turecky

For Zarelly, the doula course served to add new knowledge to aquatic and yoga therapy. “Almost always, the woman is unaware of her rights, what she can ask for in her birth plan. [Also] I support the mate or companion. The positions, breathing, the use of the ball, massages…,” Zarelly cited as examples.

“We make sure that they are cared for. We don’t say what to do, but we support the mother’s decision, we give alternatives and we inform,” she added.

“Supporting women is a political and revolutionary act,” believes Zarelly, a doula, yoga instructor and prenatal aquatic therapy instructor. “We’re demanding rights that have been made invisible in society for a long time and we are interrupting the normality of immediacy and the intervention of women in childbirth and postpartum.” Photo: Courtesy of Zarelly Canales

Another woman certified as a doula is Monteverde neighbor Melina Chacón. Although she wanted to have her delivery at home, Rebecca Turecky, her obstetric nurse and midwife, warned her weeks before the delivery that she had low ferritin (a protein that stores iron) and that this could mean bleeding. “If you don’t raise it, we can’t take care of you at home,” Melina remembers being told.

Melina managed to stabilize her ferritin and get the endorsement to give birth at home, as she wanted.

Turecky emphasized that even when births are planned for at home, midwives know how to identify when it is necessary to go to a hospital, which shouldn’t be more than 30 minutes from where the birth is taking place. Also, they never wait for an emergency to happen. At the first warning sign, they decide to transfer [to the hospital].

An Unexpected Birth, But with a Happy Ending

Danixa felt the first contractions at 1 a.m. on a Monday That was the beginning of her 48 hours of labor. Everything was going as she planned, her doula had created the ambiance in her room like she wanted it: with dim lights and lavender aromas in the air. But on Tuesday night, more than 40 hours had passed since her water broke. The pains were very intense, but her dilation was barely three centimeters.

“We need oxytocin for the uterus to contract and to go into active labor, but there is something that might not be allowing you to produce enough,” her midwife told her. “The other option is to go to the hospital for them to give you oxytocin,” she told her, and after thinking about it, she agreed.

Danixa moved to a house in San José to have the experience of giving birth at home with her family. In Guanacaste, there are no obstetric nurses who care for pregnant women who want to give birth at home, according to the women who spoke with The Voice. Photo: Natalia Rob Photography

“See how hard it was for me because giving birth at home was my dream,” she said. She did not want to give birth in a hospital because of the environment nor did she want to be in a hospital environment, but she thought it was the best option. They put clothes on her, got in the car and arrived at the medical center in a few minutes.

Just as she had done at home, the doula turned off all the lights in the room and the freezing cold air conditioning, and applied the lavender essential oil. Danixa was barely three and a half centimeters dilated, so they waited for the hospital doctor to give her oxytocin.

But while they waited, about 20 minutes passed and Danixa, lying on her side, felt like pushing. In that time, she had dilated to 10 centimeters and she got settled on the bed to push. She spread her legs, with her husband, her midwife and her doula next to her and, in four pushes, Franco was born before the doctor arrived.

“It was as if he had been born at home because all the people I wanted to be there were there. And everything was dark, it smelled nice, without air conditioning, warm,” she recalled.

“Society would change completely if women were supported by more women,” said Danixa after telling about her experience. “We achieve everything thanks to living in a tribe,” one that she is part of as a lactation consultant through her venture My Breast Friend.

The Route to a Respected Birth

- A respected childbirth occurs when pregnant women are supported by professionals, in a warm and polite environment. They respect their body, their human physiology and their babies.

- You can find out about your rights with the CCSS’s “Comprehensive Care Guide for Women, Boys and Girls in the prenatal, birth and postpartum period.”

- Talk to your doctor about your doubts and expectations. You have the right to request and obtain information on the process, procedures, treatments or medications that will be designated.

- Your doctor should pay attention and be willing to support you in a respectful and professional manner.

- You have the right to make your birth plan. There you can detail your preferences for the time of delivery: who will be present with you, in what position you would like your baby to be born, whether or not you want to receive painkillers. Your doctor can support you in preparing the plan.

- Pregnancy and childbirth are natural processes, so medical and technological intervention should be as little as possible. They must inform you in case any intervention will be done.

- Keep in mind that episiotomy, an incision in the perineum to widen the vaginal opening commonly called a “piquete” in Spanish, is not a technique that should be used regularly. Only in very necessary cases, for example, when there is a complicated vaginal delivery or fetal distress.

- Staff should place your baby on top of you immediately after birth and allow skin-to-skin contact.

- If you have any disagreement regarding care in a public health center, submit your complaint to the CCSS Services Comptroller in three steps:

- Write the complaint by hand or type it on a computer.

- Include your personal data (name, identification, contact telephone number) and sign it.

- Deliver it to your health center’s Services Comptroller ( Contraloría de Servicios) no later than five days after the disagreement occurred.

Source: Comprehensive Care Guide for Women, Boys and Girls in the prenatal, birth and postpartum period

Comments