“It was like jumping into the water without knowing how to swim.” That’s how artist Vicky Naranjo described the situation during almost eight months of the pandemic as different solutions have emerged in response to the social, economic and health turmoil that still has the people of Guanacaste filled with uncertainty.

A Guanacaste put under found themselves searching for solutions when tourism came to a halt.restrictions as measures were announced like the closure of beaches, bars, hotels and parks; a desolate town, full of questions without many answers; and tourists waiting for a green light to go back home. This is what the province experienced during the first days of the pandemic.

From this downpour of unknowns comes this feature story: not just to report on what Guanacaste experienced during these months of crisis due to COVID-19, but to portray how the communities of the province looked for solutions to reverse the situation caused by this crisis.

After almost eight months of phone calls and interviews via Zoom, genuine stories emerged from people who raised their voices, wanting to return to what they once called normal.

As the community of Santa Cruz began to receive free psychological support, a small group of people from Playas del Coco decided to go back to trading as a method of payment; and about 130 kilometers (80 miles) away in Punta Islita, the unforeseen happened: an animal conservation center found a historic quantity of macaw eggs, after being on the verge of closing its doors.

These are some of the initiatives that arose during the crisis in the province, without knowing what their impact would be. It all started as a quick response to the uncertainty in the region, thinking that the pandemic would be over quickly, but it wasn’t.

In recent months, these ideas have been transforming into solutions that are sustainable over time, even capable of changing the course of life for some who now find themselves wondering what would have happened to them without that push.

How did these solutions evolve during these months, and what would have happened to the men and women of Guanacaste without their support? We invite you to journey with us to explore each of them.

Art and Mental Health

Arte a la Mar wants to help boys and girls like Mateo and Sebastian (in the photo) to explore their creative capacity so that, through art, they can express what’s inside them beyond what they see. (Photo by Vicky Naranjo from Arte a la Mar).

Before the pandemic, she painted paintings that were mostly bought by tourists, but her income was sapped after the border closures.

In the midst of a difficult environment but with a clear objective, artist Vicky Naranjo created an initiative in Nosara to address the mental health of children, who also suffer from isolation being shut in due to the coronavirus.

“Arte a la Mar (Art by the Sea) came about because I needed this situation to make sense. I couldn’t sit around without doing anything. So I started selling my art to make some money, and I started to see that it was not just affecting me, but also the children. And so, with hygiene protocols and in a little social bubble, I began to give them painting classes,” commented artist Vicky Naranjo.

At first about four little ones showed up for each class, but over time they became more animated, growing to about ten in each session.

The classes not only allowed Vicky to generate income for her personal expenses but also opened doors to new projects.

This got started to help children more than anything else, but it also made the opportunity of other projects possible. That is to say, I also grew as an artist, which is very difficult in Costa Rica,” she added.

Andreina Lopez, the mother of one of the children participating, appreciates the importance of a program like this at times like these.

“My son is quite an artistic little person. He loves to paint and spend time creating art. And since they haven’t been able to go out to the parks and share, this project was important for them to have this opportunity to paint, learn, create and develop,” Lopez remarked.

Support and Entrepreneurship

CEPIA is one of the organizations participating in the campaign Juntos por Guanacaste. Photo by Silvia Gutierrez.

The pandemic closed the doors to international tourists and local traffic restrictions made it difficult for national residents to visit the beaches for many months.

“I worked in tourism for 20 years with tourism, but with this situation, I had to stop working cleaning cabins. Everything was closed and there was no way to work anymore,” said Santa Cruz resident Aydelina Narvaez.

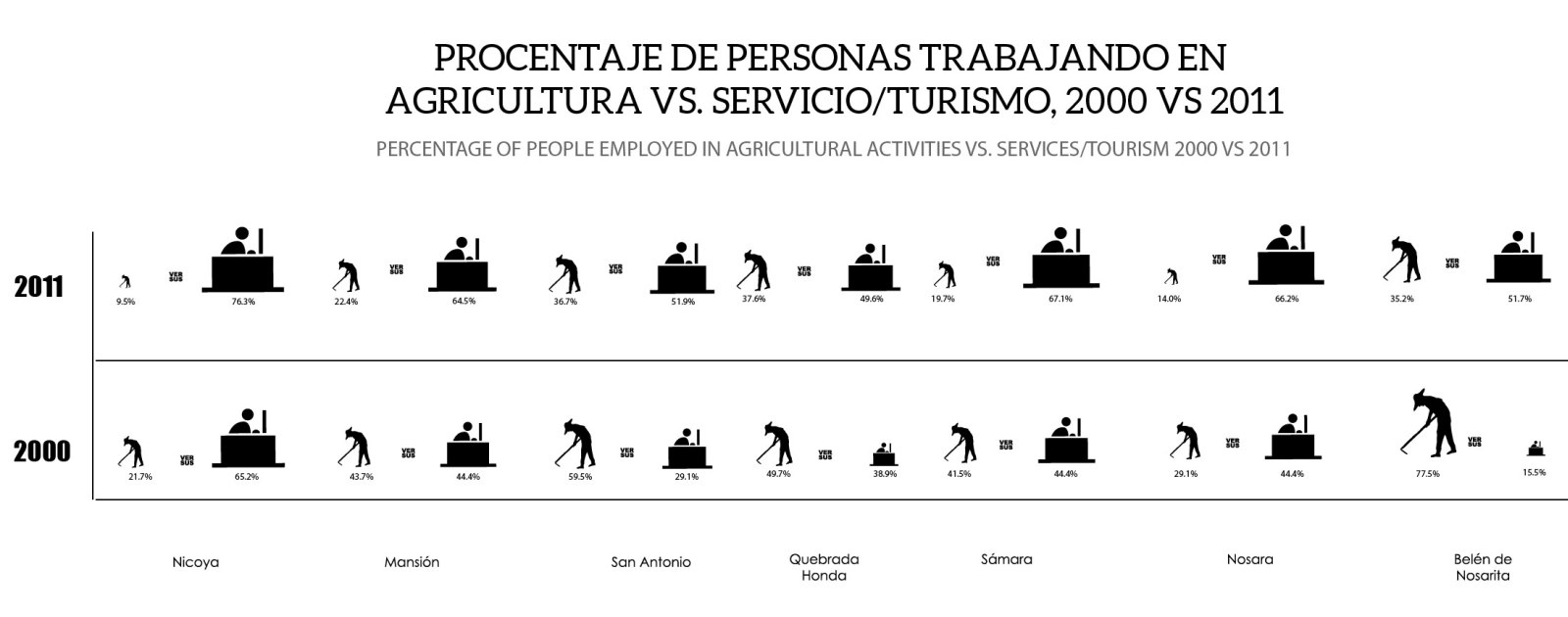

The blow was inevitable for a province where 59.4% of jobs are concentrated in the tourism industry, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INEC).

In the face of shrinking economic activity and rising unemployment, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) like Futuro Brillante (Brilliant Future) and CEPIA sounded the alarm and launched initiatives to respond to the outcry from Guanacaste families.

That is how Juntos por Guanacaste (Together for Guanacaste) came about, focused on distributing baskets of food and basic need items, such as liquid soap, disinfectant wipes and hand sanitizer. The beneficiaries? Families in Guanacaste who lost their jobs in a total of 31 communities, including Tempate, Huacas, Matapalo, Salinitas, Playa Grande, Flamingo and Santa Rosa.

The campaign brought together different non-profit organizations, including CEPIA, Futuro Brillante, Abriendo Mentes (Opening Minds), ConnectOcean and Conectando Corazones (Connecting Hearts), as well as the Tamarindo Integral Development Association and the Conchal Reserve.

“We had to learn over time. When you guys called us for the first time, we were just getting started with Juntos por Guanacaste and planning the distribution of basic baskets,” said Futuro Brillante’s executive director, Lindsay Losasso.

We had no idea that it would grow so much, nor that it would extend for so many months. We not only helped; we learned a lot about what people needed,” added Losasso.

The initiative started in a hurry and almost seven months later, it serves more than 12,000 people throughout the province.

“Without this help, we wouldn’t have the hope that they gave us in these last few months. We wouldn’t have anything to buy food with, because my husband⎼ who worked as a gardener⎼ ended up without a job due to this pandemic, and since little by little he is losing his sight, we don’t know how long he’ll be able to work,” related Petrona Salgado, from Matapalo in Santa Cruz, who has received basic baskets since the beginning of the pandemic.

CEPIA is also training 20 women from the community of Huacas and surrounding areas to make and market bags during the crisis.

CEPIA’s executive director, Maria Jose Cappa, explained that the organization saw the need to give them tools to generate their own income.

“We were afraid that the food support would generate a feeling of resignation and that the families we supported wouldn’t look for ways to reverse this situation. So we started giving classes on making bags to women, so that they would have something to work with,” Cappa explained.

Aydelina Lopez is one of the participating women.

With this pandemic, one was left not knowing what to do, empty-handed. It was with these little bags that one began to see things more clearly. Now there was a way out for us,” she explained.

“I really don’t know how we’d be with all this unemployment. One always tries to find a way out, but it wouldn’t be so easy without this assistance. That’s why you have to take advantage of opportunities,” added Narvaez.

These organizations work on other projects that will last beyond the crisis: community gardens, training on producing natural jellies and financial aid for buying egg-laying hens.

Fishermen’s Market

Fishermen became unemployed due to quarantine measures and losing their main markets: hotels, restaurants and fish markets.

The Guanacaste Chamber of Fishermen (CPG) launched the Arroz y Frijoles (Rice and Beans) initiative in May, with the support of the Costa Rican Institute of Fishing and Aquaculture (Incopesca). The goal: to allow fresh fish to be bought and resold at farmer’s markets.

According to CPG president Martin Contreras, the fishermen went from not reporting any sales to marketing about 1,600 kilograms (3,500 pounds) of fresh fish every weekend at the markets.

Dehivis Jimenez, who is a fisherman in Playas del Coco, commented that the CPG’s resources weren’t enough to help all those affected.

The chamber started with little money, which limited their ability to keep growing to try to help other fishermen. And as you may know, the government as such has always left us abandoned. Today if it weren’t for the intervention of the chamber, we fishermen wouldn’t exist,” commented Jimenez.

CPG’s president, Martin Contreras, told The Voice that the institution contributed ₡10 million (about $17,000) for the project to pay for transportation, administrative personnel and the salaries of seven new employees, who work in cleaning, buying and selling the fish.

The Chamber has helped 339 fishermen (270 men and 69 women) during the pandemic, Incopesca told The Voice.

Trading: Alliances During the Crisis

Entrepreneurs from Playas del Coco revived trading as a payment method due to the need to form alliances in times of crisis.

“I put trading into words and into action. I don’t want to consider myself the one who invented trading in El Coco. But I am happy to see that people are pushing to get ahead. They aren’t staying at home doing nothing. Rather they are looking for ways to start something in this pandemic,” explained the French creator of the initiative, Marie DeFlandre.

The product exchange went from being used by 14 people at its inception to more than 50 now. The initiative resonated in communities throughout the country, so much so that in May, the most read solutions article by The Voice explained how and why the trading arrangement came about in Playas del Coco.

People I didn’t know contacted me from all over to ask if I traded or to find out how I did it because they wanted to apply it in their communities,” DeFlandre added.

The PezGallo Design Studio of Argentine photographer Mariana Baisotti turned to trading and it yielded results.

“Between my partner (Ariela Rojas) and I, we formed PezGallo Design Studio, and we joined the Playas del Coco trades. We saw that it was an opportunity for people to get to know our work and also to create a portfolio of clients for when all this is over,” the photographer explained.

“We started exchanging photographs to promote the products of small businesses that make up the trade [alliance], in exchange for food, for example, and with that, we grew as a company,” she added.

Baisotti stressed how her situation would be without these trades. “It would be more complicated for us due to the economic issue, since many people want to work with their products’ image, but since it requires an investment, they can’t because of the pandemic.”

Animal Protection

The Macaw Recovery Network fights against the extinction of parrots in Punta Islita. The Las Pumas Rescue Center and Sanctuary, for its part, is dedicated to rescuing, rehabilitating and sheltering different animal species in the south of Cañas.

Their main source of income came from visitor entrance fees, but that dropped due to opening restrictions. Their work was in crisis, but the story doesn’t end there.

Both organizations devised strategies for receiving donations.

The Macaw Network began posting videos on YouTube to inform volunteers and donors of the parrots’ status. Meanwhile, the Las Pumas Center launched virtual visits to its facilities at a cost of ₡2,000 (about $3.50) per person.

In September, the Network tallied 21 of these birds’ eggs hatched: a historic event for the organization.

The institution’s public relations manager, Sady Gonzalez, explained that this surprise happened thanks to the decision not to close the center despite the scourge of COVID-19.

She also said that the pandemic served as a learning experience. “For us, it has been quite an experience. When you called us, we didn’t think that this situation would last so long, but we have been managing. We have less visitors now, we work with videos on YouTube, we reduce the use of cars so as not to spend so much on gasoline and we continue to care for the parrots, even in the middle of this,” Gonzalez commented.

For its part, the Las Pumas Sanctuary has had visitors in a regulated way under security protocols, which has allowed them not to close completely, in addition to virtual visits.

“Virtual visits were promoted, but it had very low participation, perhaps because they didn’t want to pay for this type of visit,” said the senior biologist of Las Pumas, Esther Pomareda Garcia.

However, schools were the ones that showed the most interest. We have already done seven virtual visits with schools and we have one scheduled for November,” added Pomareda.

Telemedicine Takes Off

The patient came through the door timidly, his head down, responded mechanically with a few words and sat down at a table. On it, sat a pen and a sheet of paper waiting to be signed. “Doctor, I can’t manage to read it. I didn’t bring my glasses. Can you read it to me?” he exclaimed.

It wasn’t a doctor seeing him. It was a nurse, Luis Cerdas, who is the telemedicine coordinator. “Sure, I’ll help you,” he replied and helped the patient.

In a chair in front of the computer, Cerdas opened his drawer and took out a futuristic-looking camera that captured the patient’s attention, a man who has fungus on his hands and needs a specialist to examine them.

“You see, this is how teleconsultations are, all very simple. Now that I have these photos, I can send them directly to the dermatologist to examine them. Most likely, the patient will return for other tests or will receive a call from the doctor to give him instructions,” explained Cerdas.

For more than ten years, the hospital in Liberia has done a small percentage of medical appointments through telemedicine, but the model of care changed and grew.

“Needs changed with the arrival of the coronavirus,” said nurse Cerdas. Since the pandemic hit, telemedicine has gained momentum in patient appointments. The same thing happened with other training sessions or meetings, such as psychological care for adults, the elderly and children, prenatal chats, appointments with pharmacists and the hospital’s administrative meetings.

The medical director of Liberia’s hospital, Dr. Marvin Palma, estimates that the hospital currently has 55 medical appointments a week. Between March and October, they have managed to care for more than 1,800 patients.

With almost two months left in 2020, the medical center was about to surpass 2,000 telemedicine appointments, which was the annual average that it had been showing in previous years in this format.

Cerdas explained that the pandemic allowed them to demonstrate the benefits of telemedicine.

I don’t want to sound like a telemedicine positivist, but the effects have been there for a long time. The difference is that today the pandemic gives us the opportunity to show the use of telemedicine as a letter of introduction to those who had doubts about its effects,” Cerdas added.

Psychological Support

In April, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned about the impact that prolonged isolation, fear of the pandemic and unemployment could have on people’s mental health.

With the same concern in mind, the non-profit organization CEPIA developed a project to provide free psychological support to men and women in the communities of the canton of Santa Cruz.

The initiative, supported by the organization’s psychologist, Patricia Leon, was created to prevent an increase in mental health-related illnesses and in the suicide rate, which is higher in Guanacaste.

“Being shut in causes a lot of stress. The things we did before can no longer be done, the life we had before is no longer the same. But the worst thing for Guanacastecans was the worrying caused by unemployment. They stopped sleeping well and stopped eating well,” commented Leon.

In August, the program tallied that 250 patients had been cared for, out of a total of 600 requests. As of October, 391 people had been reached.

These nearly 400 people have shown their appreciation for the program, and to psychologist Leon, this is a step to show that mental health matters too.

“The sad thing is to see that no one has dealt with this yet. They aren’t seeing what this pandemic could cost us. We’ll see not only cases of infections, but also cases of depression, or even more worrying, suicides,” she added.

A resident of Huacas in Santa Cruz, Belkis Gutierrez stressed the importance of companionship during these months. “At the beginning of this pandemic, I would think a lot about all this and it wouldn’t let me sleep. It would stress me out a lot and I felt bad,” Belkis said.

The truth is, I don’t know what we would have done without that support from Dr. Patricia. We would be suffering more, for sure we would be. Sometimes you don’t pay attention to these things, but they are very important in order to live,” added Gutierrez.

What started as a concern months ago became a reality. During the press conference on October 9, the head of the Mental Health Department, Francisco Golcher, explained that the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS) reported more problems with anxiety, panic attacks and depression during the economic, social and health crisis.

For Guanacaste, this is not a minor concern. In 2018, an article published by Semanario Universidad on the suicide rate in Costa Rica showed that suicide affected 7.2 out of every 100,000 inhabitants, mostly affecting men, mainly from the province of Guanacaste.

In the canton of Santa Cruz alone, the suicide rate reached 21 out of every 100,000 inhabitants, for a total of 14 suicides in that same year, Semanario Universidad reported. One of the main factors that led to this type of death in the canton of Santa Cruz was unemployment.

How Guanacaste Responded

During these seven months of reporting and following up on solutions in the province, these initiatives showed Guanacaste’s resilience in the face of the COVID-19 blow.

Amidst difficulties, limited budgets, alliances and the need to reinvent oneself, solutions emerged in the communities most affected by the pandemic, where employment levels fell overnight.

A portion of the province decided that waiting for a lifeline wasn’t an option. “You can’t stay there waiting for them to come and help you. It doesn’t always happen that way. You have to get to work, and this pandemic taught us that, jumping into the water without knowing how to swim,” concluded the artist from Nosara, Vicky Naranjo.

Imagine a Guanacaste without these initiatives. The communities affirm that they would still be waiting for help or economic reactivation.

Each initiative says that this would have been the most likely fate: the fishermen in Playas del Coco would have no income, the rescue centers would have closed, nearly 400 people in the community of Santa Cruz would be waiting for psychological help, hundreds of people wouldn’t have received medical consultations and many more households wouldn’t have had anything to eat for months.

October has come to a close and the end of the pandemic is still uncertain. The economy hasn’t been reactivated either. In the midst of this uncertainty, many of the solutions that initiated in the province in response to the social and economic problems that the crisis unleashed are now poised to stand the test of time, even after the storm has passed. So the pandemic may come to an end, but the solutions won’t end with it.

Comments