More than 25 years ago, Fernando Ajú planted rice during the rainy season and melon during the dry season on a farm next to Coyote Beach in Guanacaste. His wife, Jenny Calvo, was in charge of the logistics of selling the product within and outside of Costa Rica. Both as a family and a traditional business, Melones de la Península grew.

It wasn’t until 2014 when the business changed with the lead of their son and daughter, Ocksan and Suk Lin Ajú. The company went out in search of a much more complex business model that adhered to sustainable production. After several years, in July 2019, Melones de la Península became the first exporter of organic melon and watermelon in the country.

The Foreign Trade Promoter (Procomer) affirmed that this is the first Costa Rican company to export organic melon and watermelon, although between 2014 and July of 2019 the country did export about $78 million in other organic products such as pineapple, oranges and coffee.

The destination was Europe, an increasingly demanding market that requires exporters to diversify if they want to conquer it. By ship and by plane, the company sent 11,500 kilograms of fruit. That is still less than 1% of the amount of organics exported so far this year, but it is a first step.

Turning Point

With the vision of the Ajú brothers, Melones de la Península wanted to win two battles: to enter an organic market— still fledgling in the country— and to excel in an increasingly demanding international market.

Nationally, hundreds of families grow food through organic agriculture, but few have an official “organic” certification and even fewer manage to export those products.

According to the latest report of the State of the Nation, in the chapter “Harmony with Nature,” in the last decade, the area cultivated under the category of certified organic agriculture barely reached 3% of the total agricultural area of the country. In 2017 it was only 1.7%.

In Costa Rica, for a product to be recognized as organic, it must have an official certification issued by private certifying agencies and by the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (MAG). The Ajú family chose the Kiwa certification company to guide them through the process.

They began by modifying and reducing the application of agrochemicals through the production of biological control microorganisms (fungi and bacteria that help control pests). In addition, they opted for precision agriculture with drones and irrigation control to minimize the inappropriate use of water.

Suk Lin said that for many melon growers like them, it is practically impossible to think of producing organically because the fruit faces a lot of pressure from pests like whiteflies, which transmit virus to the crops. “It was almost a utopia.”

The company focuses on producing watermelon with or without seeds, and white and yellow melon

In fact, in 2011 the melon was among the crops with the highest presence of pesticides nationwide, according to data from the Regional Institute of Toxic Substance Studies of the National University (IRET).

With the changes, Melones de la Península succeeded in officially certifying its packaging and processing plant as organic. But for their first export, they had to ally with a company that has its farmland certified since the farm where they currently plant the fruit does not have that distinction— and that is an indispensable requirement to have the official seal.

Our technicians advised the whole process and it was as if we were renting the land to produce the fruit. Once we cut the watermelon and melon, we transfer it to our plant and there we process and pack it,” explained Suk Lin.

Between alliances and certification processes, the company was able to send 11,500 kilos of fruit abroad. It was an arduous process, but its owners do not complain.

“In five years we have reduced the agrochemical load for melon production by more than 30%, and instead of seeing our yields reduced, they have increased,” Suk Lin related.

The country of entry into Europe was Holland, a market that more than recognizes the “organic” differentiation in its consumption.

The most recent study carried out by Procomer states that for a company that wants to conquer or reconquer the European market, “reduced in” and organic products are positioned to win.

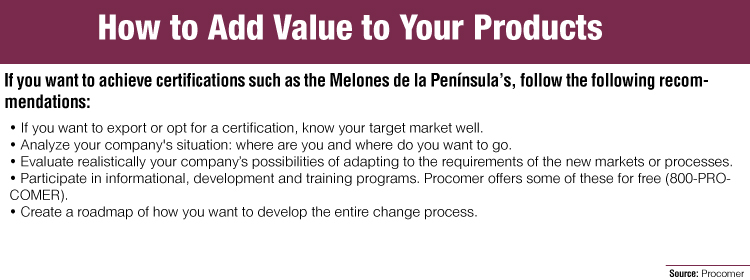

The head of Procomer’s regional offices, Gabriela Sandí, indicated that there is an international market that recognizes the efforts made by companies to differentiate themselves. That element, without a doubt, makes companies more competitive, she said.

“Depending on the market, certifications like organic are a necessity, and are the means to access new markets,” Sandí added.

Melones de la Península also has other certifications, such as the Global G.A.P., which recognizes product quality, environmental protection and employee well-being.

The Challenges

According to Sandí, one of the biggest challenges to take the step is the economic cost of the certifications, and also the internal modifications that the company has to make. The cost of a certification, depending on the type, can be between $1,000 and $4,000 per year.

Suk Lin says the company had to rethink the way they adjusted their budget. At one point, they had to stop buying a tractor to stick with the goal of being environmentally friendly.

“We also had to make changes in the plant’s cleaning products if we wanted the certification,” he commented.

In the case of organic exports, Suk Lin added that the test came out “very expensive,” but that it was necessary to do it to test processes and make corrections. “We wanted to prove that it could be done.”

In addition to money, Procomer and Suk Lin agree that proper advice is a major factor to give value to the products that are produced.

Value added is a matter of knowledge and that does not necessarily require an expense. Procomer’s advisors are free, and those interested can turn to 800-PROCOMER,” Sandí specified.

Now, Melones de la Península is preparing to make a new shipment, to certify its land as free of agrochemicals and to find a way to continue innovating.

Comments