It is 2010 and Sharon Urbina sees in the distance a turmoil of floating rocks that interrupt the azure blue landscape of Brasilito Bay in Santa Cruz. They appeared every week, after strange giant boats passed by the coast.

The rocks weren’t rocks. They were the bodies of turtles or baby sharks that had gotten stuck in fishing nets and that, like rocks, floated inert along the shore of the bay.

Urbina, 38, had seen the same scene since she was a child. According to her, those responsible were shrimp boats that came to the area from Puntarenas to fish and dumped the bodies of species that weren’t useful to them.

She saw it until 2017, when the last licenses for the practice expired. Five years earlier, the Constitutional Court prohibited the Costa Rican Fishing and Aquaculture Institute (Incopesca) from granting new ones due to the damaging impact it had on other marine species. “Since then, [our own fishing] started to go better,” said the Santa Cruz woman, who fishes from shore.

The Voice of Guanacaste looked into the new bill (No. 21478) that takes advantage of shrimp fishing in the country, consulting experts in fisheries sciences, Guanacaste fishermen, the minutes of the bill, academic studies and legislators from the region. They all agreed that the study and the law ignored the Guanacaste coast.

In 2013, the Court gave Incopesca the chance to demonstrate whether, through new techniques, it would be possible to reduce the impact of bottom-trawling on ecosystems.

The institution presented a study with deficiencies, according to the University of Costa Rica (UCR) and the National University (UNA), but this opened the way for the approval of trawling in the Legislative Assembly, with 28 votes in favor.

The President of Costa Rica, Carlos Alvarado, vetoed that bill on October 30, arguing that it lacked scientific evidence. Now, this bill is back in the Legislative Assembly, where its promoters need to get 38 votes in favor for it to pass.

“Fish Come Toward Shore More”

Coming from a family of traditional and shore fishermen, Sharon Urbina said that in the last three years (without bottom-trawling) she made a lot more money than she had since she started fishing. “The fish come toward shore more. Everything has improved since then,” she said.

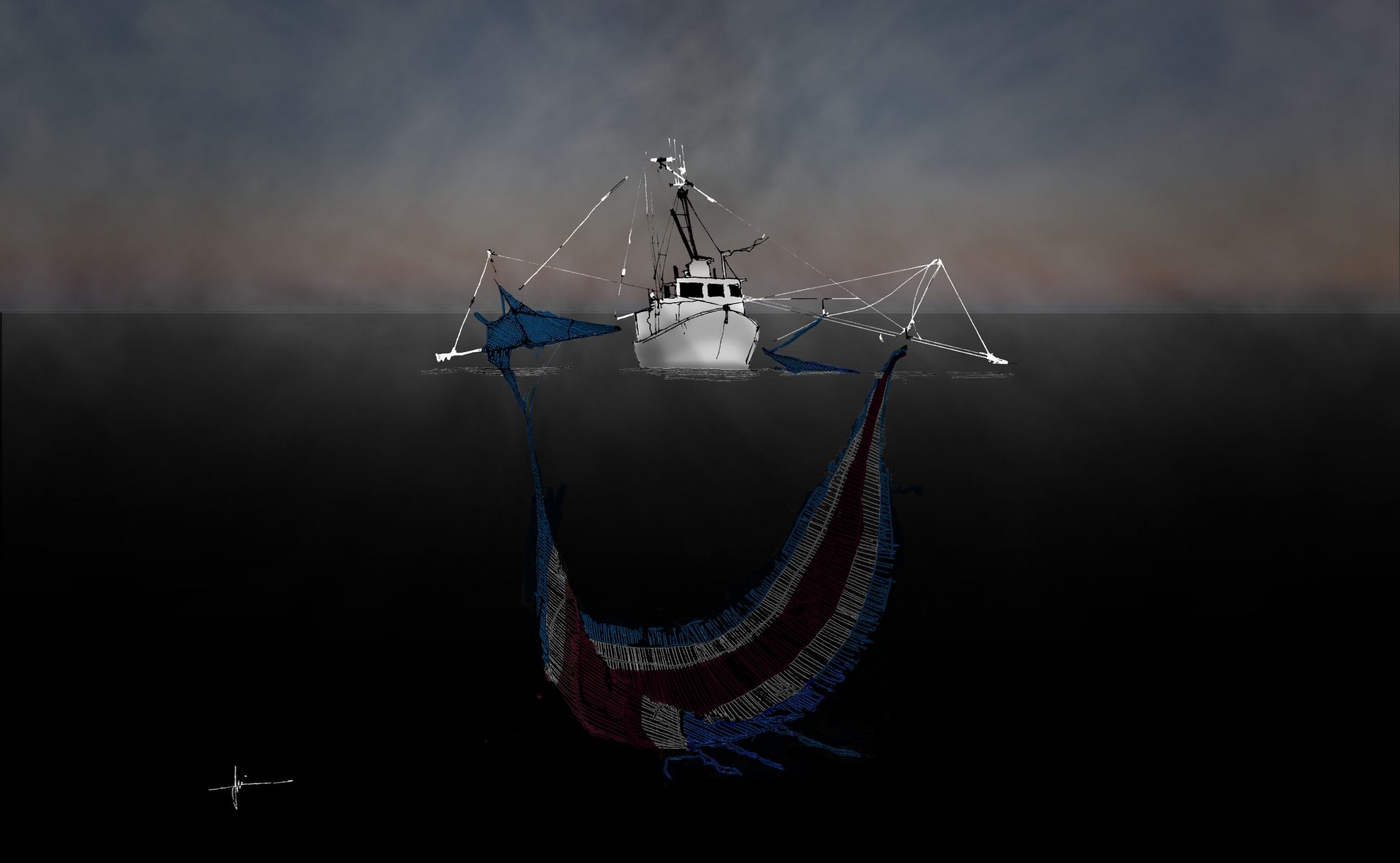

The fisherwoman can attest to this because one of the consequences of trawling, since all kinds of species are caught within the enormous nets, is that the population of other animals that traditional fishermen do target is reduced. Their work resources decrease.

Incopesca defended this fishing practice with an investigation focused on a single topic: reducing the incidental capture of species. The institution tried to test new trawl nets that would capture less of this “accompanying fauna,” as it is referred to scientifically.

According to the Incopesca study, the new nets incorporate a “turtle excluder device,” which allows turtles to escape if they get in the net. They also increase the size of the “cod end,” the bottom of the net where the shrimp end up. Since it is larger, the idea is that the small fish that inhabit the ocean surface can escape easier if they get in the net and they “obstruct less and less” of the meshes.

The director of the Center for Research in Marine Sciences and Limnology (Cimar), Ingo Wehrtmann, considers the study’s approach to be insufficient since it didn’t analyze how trawling affects the ecosystem.

Wehrtmann emphasized that this is important for Guanacaste. Shrimp (which serve as food for other species of commercial interest) start their life cycle in the waters of Puntarenas and when they reach adulthood, they migrate to the coasts of Guanacaste or Nicaragua.

Shrimp migrate. They don’t stay in one place all their lives. But there isn’t much information about those migrations either. There is no data,” said the scientist.

Although the study lacks data, even the existing data left Guanacaste out: the investigation didn’t even take samples from the Guanacaste coast to see if the nets worked there. The analysis was focused solely on the mouth of the Gulf of Nicoya in Puntarenas.

The north of Costa Rica, in Guanacaste, is underrepresented,” stated Ingo Wehrtmann.

Guanacaste’s Fishermen Absent

The president of the Chamber of Fishermen in Guanacaste, Martin Contreras, indicated that the bill not only affects the province’s ecosystems, but also the fishing economy.

In October 2019, this chamber requested to meet with the Legislative Committee for Agricultural Affairs, the entity in charge of analyzing the bill before it goes to the plenary. The legislators rejected the fishermen’s participation. “How are they going to represent us if they didn’t even allow us to express what we believed about the law, good or bad?” said Contreras.

When asked about the issue, Melvin Núñez, a legislator with the National Restoration party who is one of the promoters of the bill, said that although he was not the president of the commission, one of the reasons why they didn’t allow the fishermen to participate was due to “lack of credibility.”

Núñez stated that a few months prior, the fishermen had indicated that they agreed with his bill project.

I let them express everything they wanted and then they decided to contradict themselves,” the legislator affirmed. “In addition, they were at the Environment Commission, where they said what they wanted,” he added.

The Guanacaste fishermen did give a presentation about their position to the Environment Commission, but they didn’t do so until after the rejection by Agricultural Affairs. Nevertheless, the Agricultural Affairs Commission was the one in charge of analyzing the bill project.

The Voice also asked the legislator about the investigation that the commission conducted in the province. To this, he replied that due to his experience in Puntarenas, he had knowledge of “the needs of the province,” referring to Guanacaste.

Unemployment isn’t only in the provinces of Guanacaste and Puntarenas, but throughout the country,” he added.

Position of Guanacaste’s Legislators

During the plenary vote on the law, two of the four legislators from Guanacaste, Mileyde Alvarado of the National Restoration party and Luis Antonio Aiza of the National Liberation Party (PLN), voted against the bill. The other two, Aida Montiel of PLN and Rodolfo Peña of the Christian Social Unity Party (PUSC), were absent during the vote. The latter announced that he would vote against the law if they tried to reseal it.

In addition, Alvarado, along with seven other legislators, sent a letter to the president of the republic requesting that he veto the law.

We allow ourselves to request that, within the framework of the competencies and powers that are constitutionally assigned, consider the interposition of a veto on Legislative Decree No. 21.478, in response to the environmental protection commitments that you attend to and promote, even internationally,” the letter stated.

When talking to The Voice, the legislator affirmed that her position comes from “coherence.” She thinks it is possible that the practice damages the ecosystems of Guanacaste’s coasts, and therefore the area’s economy. “There is no study that tells me that this is not going to affect Guanacaste,” she emphasized.

Another reason Alvarado gave to justify her position is that, according to her own studies, Guanacaste doesn’t have enough coastal surveillance to supervise the practices carried out by trawling boats.

The legislator emphasized that the government should look for other alternatives to reactivate the province’s economy since Guanacaste currently depends on tourism, which was hard hit by the COVID-19 health crisis. There is data to back her up since Guanacaste lost at least 56.8% of the jobs dedicated to tourism.

Impact on Tourism

In fact, another information gap in the study is the impact it could have on tourism in the province. According to Cimar studies, when passing through the seabed, trawl nets raise sediments and create a kind of “dust cloud” in the sea. This can affect corals and reduce their visibility. The investigation, however, left this out.

That is one of the reasons why Guanacaste’s eleven municipalities and the nine tourism chambers in the province rejected the law completely.

This is not a sustainable activity, as it directly affects the sites for diving and snorkeling…. Guanacaste’s position is being ignored,” declared Cesar Gallardo, member of the Guanacaste Chamber of Tourism (Caturgua) board of directors.

***

The next step for the law would be to seek resealing within the Legislative Assembly. However, Congresswoman Alvarado thinks this is an “unlikely” scenario. “I think my colleagues are giving up on this law that is so dangerous,” she said.

Nuñez, from the National Restoration party, affirmed that if the project is tabled, he would present it again.

Shirley Urbina, the fisherwoman from Brasilito, hopes she will never again see those “rocks” that aren’t rocks, but dead animals littering the beach. “It’s something that nobody should see,” she stated.

Comments