In Costa Rica there is a conference every day in which the government (Ministry of Health and the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS)) tells us how many cases of covid-19 has been confirmed, how many are recovered, hospitalized and in intensive care. This does not happen in all Latin American countries.

There are only two data that are universally available in 11 countries of the region, including Costa Rica: how many confirmed cases with covid-19 are each day and how many have died.

Compared to the rest of Latin America, the example of Costa Rica stands out not only for its attention to the pandemic and its search for solutions against the disease, but for the amount of information it shares.

For example, only half of the countries analyzed for this report know how many intensive care beds are available. Among them, Costa Rica.

Some media and part of civil society have insisted that this information is scarce to be able to supervise the work of the government in the communities, to which the Ministry of Health has responded by adding data to those PDFs. It also publishes that information in excel, which allows some analysis, but it leads to the same information processed by the government.

That means, there is an effort and progress, with some contrasts: access to data on districts in which there are confirmed cases is still denied, but on April 16, they already provide information on the cantons to which the recovered people belong.

The total data of tests carried out in the country was revealed after many questions about it and a fake news. But we do not know how many are carried out by canton or province to know the magnitude of the disease in Guanacaste, for example.

Thereby they have been advancing. There are countries of Latin America that do not even reveal how many people have recovered, highlighting how governments are betting on communicating a minimum of data on the disease caused by the new coronavirus.

A group of journalists from 15 newsrooms in 13 Latin American countries come together to connect the dots and understand aspects of the response to the largest global public health crisis in a century in our countries and in the three states with the largest Hispanic population in the United States. We find this by looking at what information is readily available and what is not.

How many Latin Americans have covid-19?

The 13 countries analyzed update the confirmed cases of covid-19 every day, as well as those who died.

The United States is not publishing the number of people who recover from covid-19, a crucial fact because it allows us to understand the capacity and quality of response of medical centers to the number of people infected. Brazil only began to publish the data since April 14.

Costa Rica began to reveal the number of recovered by geographic location on April 16, which allows understanding how specific populations of the pandemic are emerging.

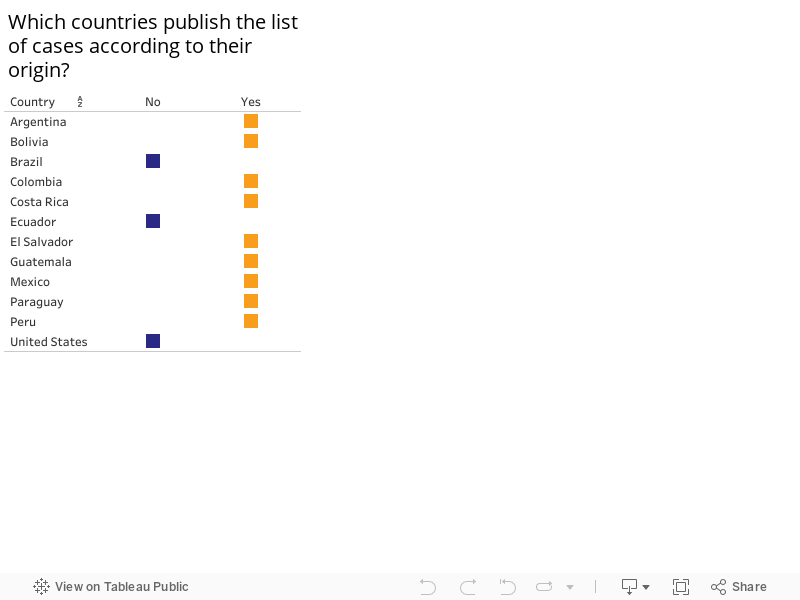

Most countries are making the origin of each case public (that is, if they are imported, if they are related to those imported cases or if it is community transmission), which helps citizens understand the spread. Three countries — Ecuador, Brazil, and the United States — do not disclose this information.

According to national authorities, Costa Rica is still in phase three, in which the majority of cases are imported or related to them. There are at least 6% of all cases without the epidemiological link identified by the authorities, Health Minister Daniel Salas said at the conference on Thursday, April 16. However, this percentage is not yet significant to say that we are in phase four or of community transmission.

Additionally, there are two countries (Brazil and Peru) that are not publishing the age range of their cases confirmed with covid-19. In Brazil, previously the Ministry of Health published sporadically the age range of patients in serious condition, but now it only reveals the ages of people who died.

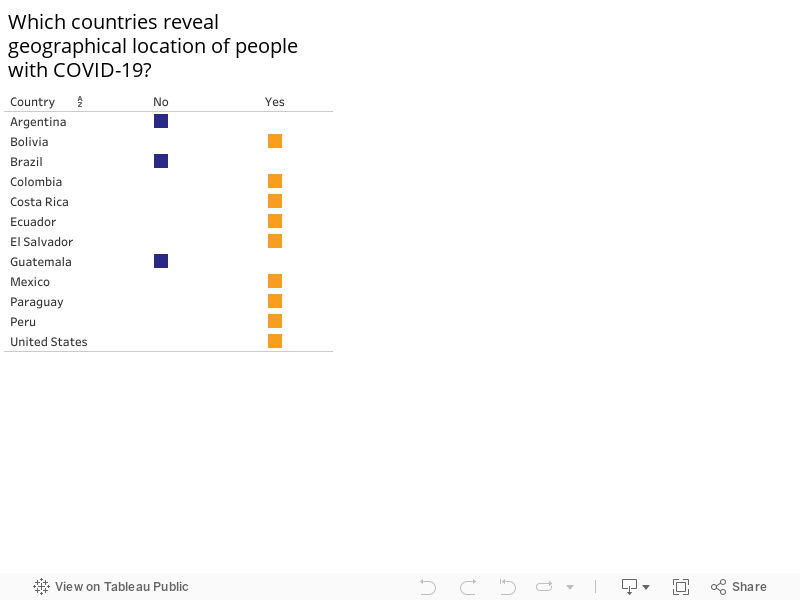

Most countries disclose the geographical location of their cases (by city or municipality), another fact that also helps to understand the regional spread.

However, there are two countries that don’t specify them on that scale. Brazil only publishes data by state and Argentina by province. Paraguay reveals the data by cities since Thursday, April 16. Before they only detailed by departments. In the case of Guatemala, the authorities stopped publishing the information from 22 departments and 340 municipalities a week ago, grouping it in five regions in a very general way. In Peru, the Ministry of Health reports data at the regional level and only in the case of Lima, the capital, at district level.

That is not the only relevant data on where the confirmed cases are. Many of the countries in the region are telling their citizens what kind of medical care are receiving the confirmed people, including whether they are at home, in the hospital, or in intensive care. Two countries (Brazil and Guatemala) do not make this data public, which allows to understand the seriousness of the state of health of those infected. Argentina reports daily only the number of people in intensive care.

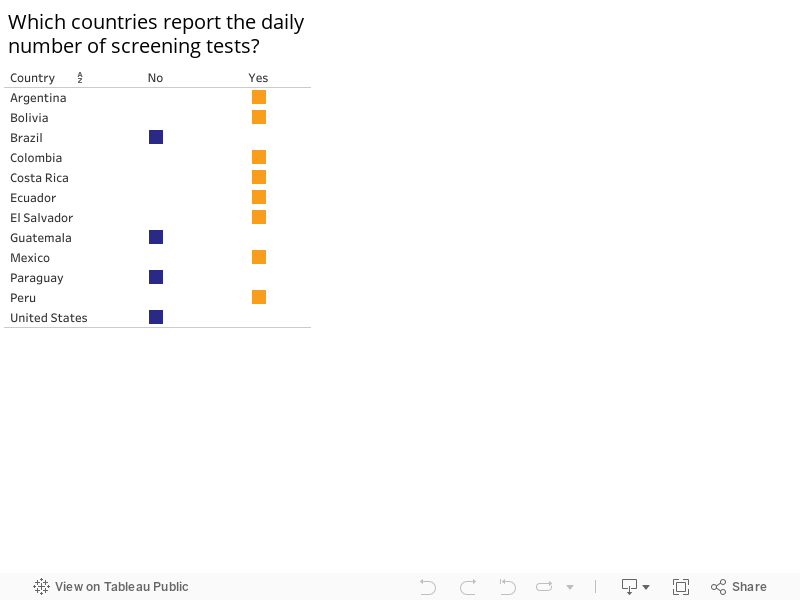

How much do they tell us about the testing?

One of the biggest citizen questions is how many screening tests are countries doing. They can be molecular PCR tests -which offer the highest level of reliability- or rapid diagnostic serological tests, which allow for wider population scans at less cost.

Fewer than half of Latin American countries consistently disclose the numbers of screening tests they perform each day. This information is published in Colombia, Costa Rica, Peru, Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador and Bolivia.

The Costa Rican Ministry of Health only began to disclose it on April 15, after pressure from the press and civil society groups that increasingly demand more open data.

Meanwhile, Colombia publishes a constant count of samples processed every day, but trends cannot be seen if not only for weeks.

Of all, only Bolivia publishes data on where in the country are them taking samples. Local media in Costa Rica, such as La Voz de Guanacaste, obtains this type of information by consulting the directors of the health areas, but often the transparency of this information is subject to the provision that each director has to give it.

Also, few countries are revealing how many tests are in processing status daily. Only Bolivia, Paraguay and Mexico do it.

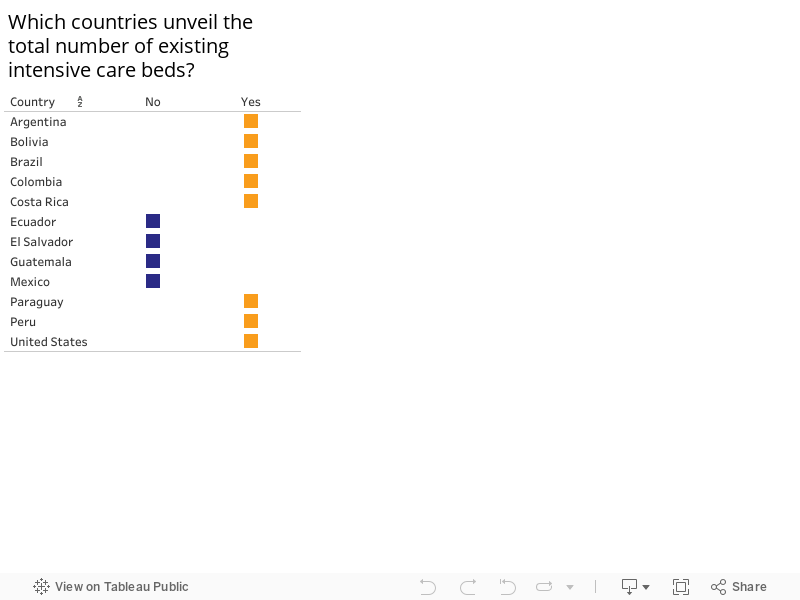

What capacity do hospitals have?

Only in half of the countries consulted there is public information on the total number of beds in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU). The data is necessary because more patients may require more specialized medical attention at the peak of the disease. Without these data, the question remains whether the existing infrastructure will be able to serve them.

Although not all covid-19 patients who are hospitalized require intensive care, it is one of the data that allows understanding the steps countries have taken to scale up their ability to provide medical care. This information is public in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Paraguay, Peru and the United States.

However, this does not mean that the information is easy to analyze. In Peru, the number of ICU beds -as well as ventilators- are not published anywhere, but are known because national authorities have revealed them in interviews when asked. Those figures are, in any case, national and there is no way of understanding how they are distributed by region or hospital.

In Costa Rica, as in some other countries, the authorities have once reported the percentage of occupancy on a given date, but there is no data for specific regions or cities, nor it is an overview that is reported periodically.

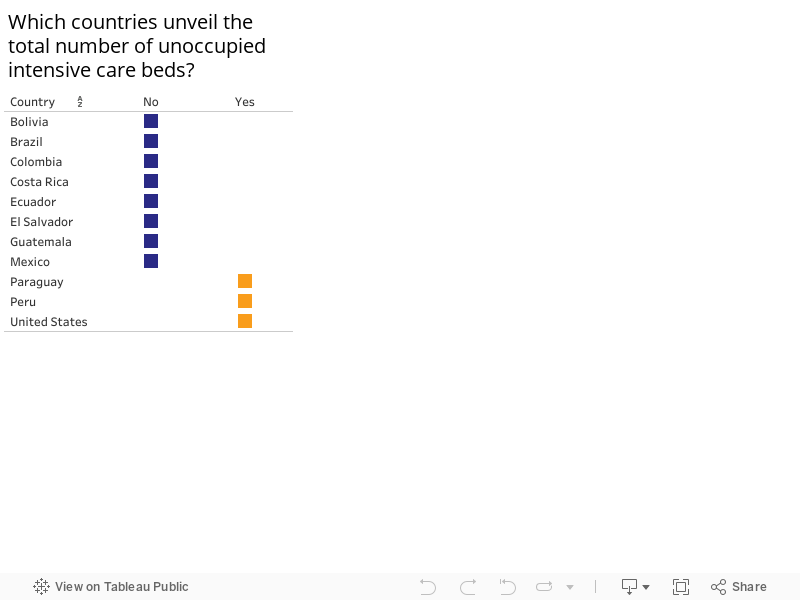

But of all, only three countries are telling their citizens how many of those ICU beds are available, as many are currently occupied by patients with other health problems. This occurs in Paraguay, Peru and the United States.

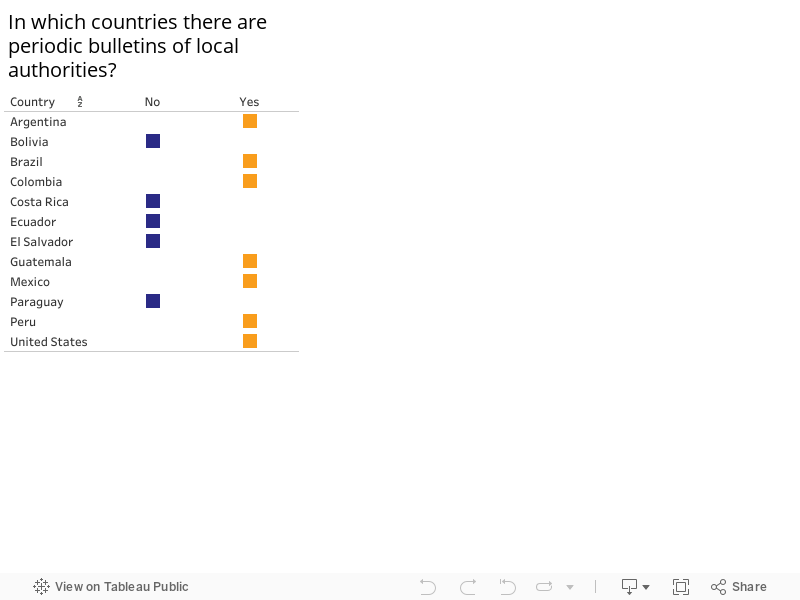

How often do authorities report?

In all countries there are periodic bulletins from government or health with updated data on the impact of covid-19. In several cases, such as Peru and Colombia, the president makes almost daily addresses on television or social networks. In Mexico and Brazil, the health authorities appear daily.

In some countries, local authorities in departments or regions supplement this information periodically with more localized data. In the United States, that public health information is fairly decentralized. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and private institutions provide more reliable data than those at the federal level.

In Peru, however, there have been gaps between the information systems at different territorial levels, with cases of patients with covid-19 or deceased who had already been officially confirmed by the regions, but did not appear in the national registry.

This occurs occasionally also in Costa Rica. For example, since April 9 the Municipality of Nicoya announced two patients who had successfully recovered in the canton, but they were not reported in the Ministry of Health bulletin.

In six countries, however, there are no periodic bulletins from local authorities, either regional or municipal: Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala and Paraguay.

This regionalized information would allow us to understand the response of the health areas and Ebáis located tens of kilometers from a hospital with greater capacity, such as Nosara, which is 60 kilometers from the Nicoya hospital on a ballast street.

Has access to information been limited?

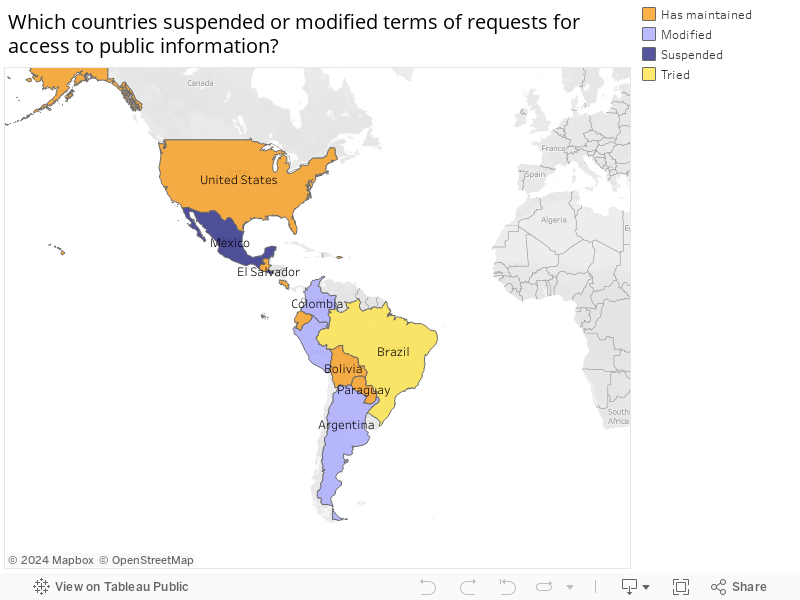

Two Latin American countries, El Salvador and Mexico, have made the most drastic decision to suspend access to public information, justifying that they are not capable in this moment because of the urgency of the response to the pandemic.

In Mexico, the National Transparency Platform suspended its terms and deadlines for access to public information between March 23 and April 17, while INAI -which is the guarantor of the right to public information- is not even sitting.

The Brazilian government also tried, but was prevented by the judicial branch. On March 23, President Jair Bolsonaro published a provisional measure that allowed federal agencies to extend the terms of the Access to Information Law, in case the officials were teleworking and without access to documentation, or that they were involved in the response to the pandemic.

It also foresaw that, in case of not receiving an answer, a citizen could send it again only up to 10 days later and that, if it had been denied, he could not appeal. The measure, however, was temporarily revoked days later by the Supreme Court Minister, so it is not currently in force.

At least three other countries modified the temporary terms for requests for public information, extending the legal deadlines or changing the response conditions. This occurred in Argentina, Colombia, and Peru. In the last two cases, the legal term to respond is longer than the duration of the quarantines decreed by their governments.

In Peru, it was also stipulated that requests for non-digitized information will be affected by the mobility limitations of public officials and that some organizations may even extend the deadlines for these procedures.

In most countries, journalists feel that responses to requests for information are taking longer than usual.

In Bolivia, which does not have a law on access to public information, the government shows openness to respond to requests, but in practice allusions to the inheritance of the previous government of Evo Morales, with lack of systematization of the information or the absence of data.

In any case, in the 12 countries, without exceptions, the circulation of journalists is guaranteed amid measures restricting mobility to the general population.

Is the work of journalists being restricted?

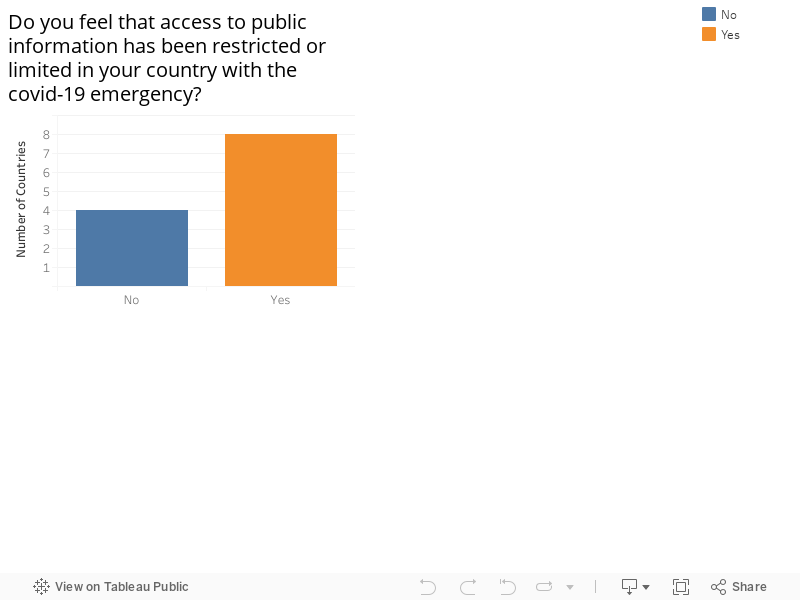

Some journalists in Latin America do feel that access to public information have been restricted or limited since the covid-19 emergency broke out.

The most extreme case is the one in Honduras, where President Juan Orlando Hernández decreed a state of emergency and suspended several articles of the Constitution, including the one that protects the right to freedom of expression.

That decision caused serious questions to the government, which reversed the suspension of the article on freedom of expression two weeks later, due to international pressure.

IIt is the type of measures that are disproportionate and that affect the population’s right to access complete information on covid-19,” said Edison Lanza, the special rapporteur for freedom of expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR).

You should not abuse those measures to limit freedom of expression, particularly at a time when the media plays a critical role in keeping society informed and safe,” said the global Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Beyond Honduras, in at least eight other countries journalists cite less availability of public information.

In El Salvador, the government restricts who has access to public information spaces and does not allow questions to media that it considers critical, including El Faro, a member of our alliance.

Although, Nayib Bukele’s government has been emphatic that it does not seek to restrict the right to freedom of expression, in practice it has been the Legislative Assembly that has managed to safeguard it. For example, when it approved the state of emergency, it was the Assembly that included an article that states that the Government cannot limit freedom of expression. Also, when it approved emergency funds through millionaire loans and authorized the suspension of the Contracting Law to allow rapid purchases, the legislature incorporated clauses that prohibit the reservation of information.

The information and response offices (OIR), which must ensure respect for the Law on Access to Public Information, are not working and announced that they would only accept requests for public information after completing the decreed quarantine, so in practice, the Salvadoran government has managed to temporarily restrict access to information.

Complaints that the information available is limited are frequent, including that it has become more difficult to obtain data in addition to what is already public and that there are no answers to questions asked to the authorities.

Despite the fact that in Costa Rica the government enabled a WhatsApp group for journalists to ask questions in conference, there is always the possibility that the queries are not read or that the authorities do not give a concrete or clear answer. This mechanism leaves us without the possibility to cross-examine.

The College of Journalists called on government authorities to rehabilitate face-to-face conferences, claiming that the current conference is not a press conference. They also requested that they limit access just for the formally established media.

In Guatemala, the communication secretary of the Presidency has blocked the participation of journalists for several days in the official government information chat to avoid questions about the management of the health crisis, for which a statement signed by 97 communicators was published .

Although journalists do not feel that their governments are using this juncture to restrict freedom of expression, they do believe that public health information systems are not sufficient to allow rigorous evidence-based journalism that attempts to look at the response to covid-19 in its complexity.

In Ecuador, for example, the government of Lenín Moreno created a mechanism for virtual press conferences through which journalists sent their questions, but there was no clarity about the process to select them, or who did it. After a public complaint signed by several Ecuadorian journalists, the press conferences are now held by Zoom with the possibility of questions.

In Peru, journalists ask for more segregated information from the Ministry of Health in their daily reports, including the demographic characteristics of the positive cases as well as the deceased. In addition, they ask to report on the regions with the same level of detail with which they report on Lima, both the patient data and the number of equipment and beds available.

Comments