Every time Valeria Briceño speaks, what comes out is a stampede of fast and forceful sentences. Her words broadcast far in all directions. She explained that this is “her theatrical voice.”

Since she was a child, she has not fulfilled the roles that others expected of her. She never wanted to play with dolls, nor did she want to stay in the kitchen where “women should be.” Now she’s 27 years old. It’s been almost a year since she went through the deepest hole of her depression.

When she opened her eyes to the different types of violence she has experienced during her life because of being a woman, she looked in the mirror and didn’t like what she saw.

“Realizing absolutely all of that was an emotional blow. What are you doing with your life? It’s like the pain before managing to forgive yourself,” she related.

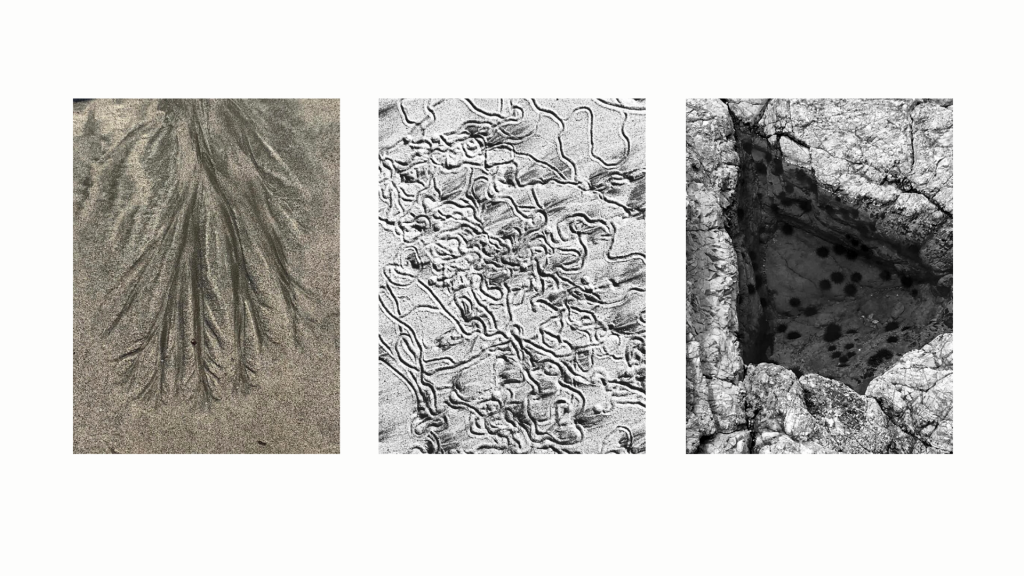

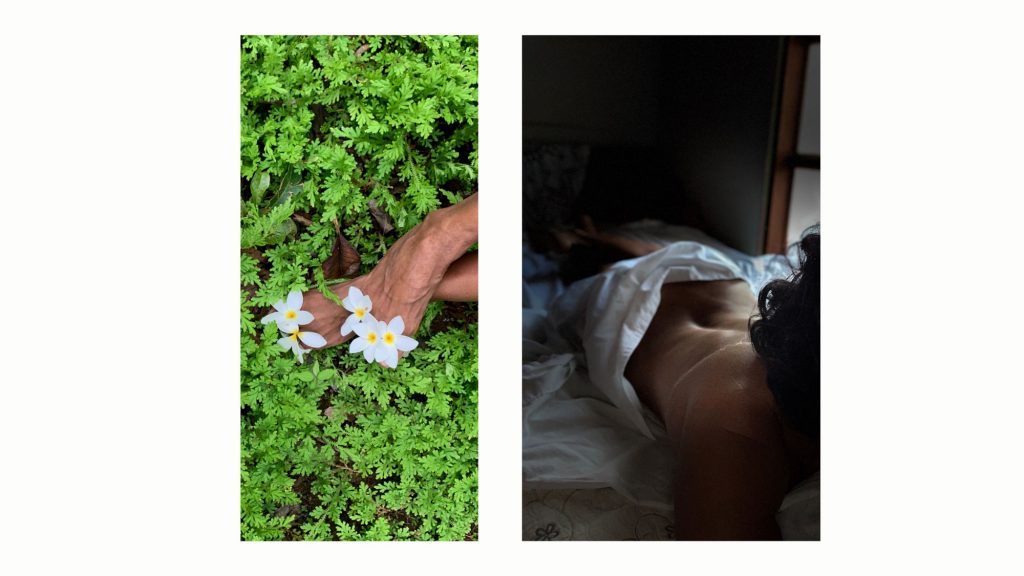

Now she is starting to feel better as she works through her insecurities in different ways. Photography has helped her in this process.

Worth More Than a Thousand Words

“I am a little squarish because of my build, so in my family they called me Tamale. And one day I took a photo of myself scantily clad and said, ‘I’m going to put hashtag tamales.’ It’s like saying “well, this makes me feel bad, but I’m going to use it to my advantage.”

With the goal of continuing to learn about this new way of expression, she participated in the workshop that photographer Mari Arango held with women from Nicoya between August and October. This was one of 38 projects in Guanacaste that won special grants from the Ministry of Culture and Youth’s Creative Scholarship Fund.

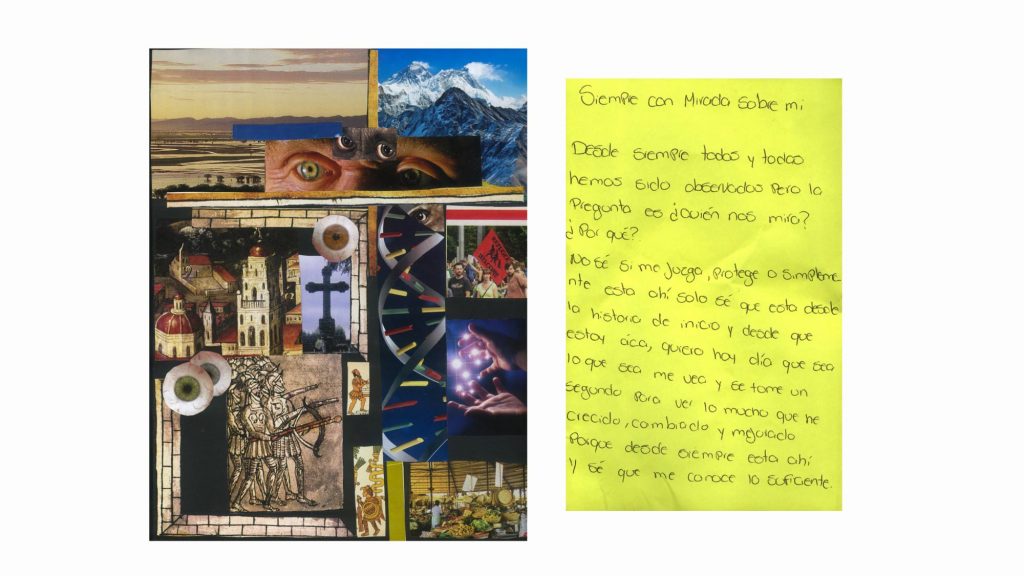

Valeria and nine other Nicoyan women explored their own lives through images for three months. The workshop taught them to use photography as a blank canvas to express their experiences, desires and emotions.

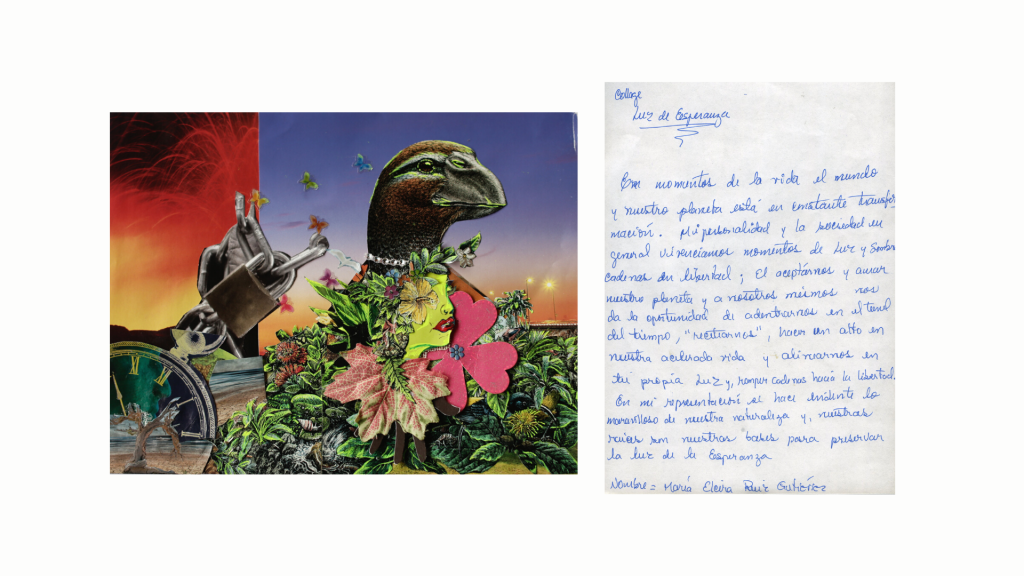

Students, entrepreneurs, broadcasters and teachers of all ages used photography and collage to reflect on their daily lives. Some of them, like Valeria, have gone through circles of violence. Others haven’t, but their images eventually became diaries that capture moments to tell about their personality and worldview.

Credits: Dunkan Harley

“The workshop was created with the intention of using photography as a new tool for the transformation of women from rural areas,” the photographer commented.

During the classes, they learned design concepts and techniques to better use their cell phone cameras. But the interesting part came later, when they talked about the images they had created in discussion circles and described how they made them feel.

“By listening to the stories of each of the participants, we understood that our past does not define us or make us less strong. This was something that we kept in mind from the first class to the last, how strong and resilient we all are,” Arango added.

Valeria recalls that each class wasn’t just an opportunity to learn theory, but she also found a teacher in each of her classmates regardless of age or academic grade.

Credits: Valeria Briceño

Letting Go of Regret

In the middle of a six-year courtship, Valeria realized that she no longer wanted to stay in the relationship. Her partner at the time told her how to dress, controlled which friends she could go out with and pressured her to have sex when she didn’t want to.

“I didn’t know that this was rape and, well, I lived through it for a long time, and I didn’t realize it. They are things that I’m learning now over time,” she added.

One story after another exemplified the psychological and verbal aggressions that she experienced, which led to a “trauma that left her self-esteem at rock bottom.”

“This eye-opening process doesn’t cloud the soul, but it hurts, because it weighs on you when it comes to releasing it,” Valeria said as if reciting a poem at full speed.

It is a slow process with ups and downs, which is why she still finds herself repeating behaviors that are consequences of her old relationships.

“You tend to unconsciously look for patterns and when you don’t find them, you’re like, where’s the jealousy? Where are the fights? He doesn’t care about me because he’s not jealous of me! And it’s the same psychological damage,” she added.

She has noticed that the opportunities to address these issues in Nicoya are almost nonexistent, due to the fact that women who fight against gender violence are singled out. According to Valeria, negative comments from people are very inhibiting for those who still find it difficult to come out of their shell a bit more.

When she took the workshop, five months had passed since the first case of COVID-19 in Costa Rica, and the effects that the pandemic brought made these programs even more necessary.

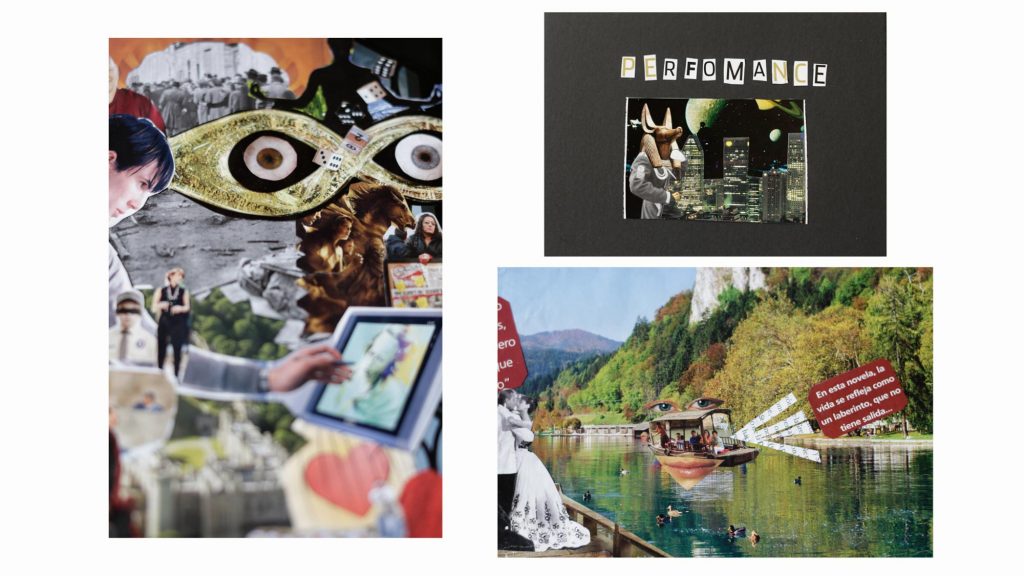

Credits: Jenny Toruño

Collage of various workshop participants

Images Against Isolation

Week after week, the classes were filled with landscapes, nudes and details. A woman photographed her semi-nude body for the first time. Another paused to enjoy the colors of the neighborhood where she walks every day. One more recorded the exact moment when she opened her beauty salon.

Elcira Ruiz is an extroverted and cheerful 57-year-old retired teacher who confesses to frequently filling up her cell phone memory with photographs. “For me, photography meant taking back the right to continue imagining and to tell life in images,” she said.

Two Saturdays a month, these women found an opportunity to talk and set aside for a little while the situation we are going through.

The health and economic emergency caused by COVID-19 brought many negative consequences for our country, especially for women. One of them has been being overloaded with chores at home. Although this perception hasn’t been confirmed with data in the country, in some nations such as Argentina, there are surveys that support it.

For Gladys Avila, another participant, the workshop became an escape to forget about the crisis.

“It allows [the participants] to get out of the house and be doing something that is not thinking about the economic situation, or the health problems that each person may have, according to the situation we have today,” she commented.

Credits: Gladys Avila

Credits: Jennifer AlvaradoPhoto: Credits: Jennifer Alvarado

Being overloaded with domestic chores is just one of the manifestations of gender violence that some Nicoyans experience in their homes.

According to an analysis done by The Voice of Guanacaste, between 2015 and 2019, the Family and Domestic Violence Court of Guanacaste Judicial Circuit II reported 4,569 complaints of domestic violence in Nicoya. This is the canton with the second most complaints, only lower than Santa Cruz with 6,039.

“I can assure you that in Nicoya, it is the first time that such a program has taken place. And it was very much taken advantage of because in rural areas, there is still a much larger gap,” explained Patricia Ruiz, one of the workshop participants who is a survivor of domestic violence.

“Here we have women, let’s say a little empowered, but hopefully we can reach those women who don’t feel like talking or you see them as withdrawn. Perhaps in a photograph, they can say everything that they hold in in their feelings,” added Patricia.

Credits: Patricia Ruiz

Credits: Elcira Ruíz

Documentary photographer Gabriela Tellez, who is part of the Nomad Collective, believes that talking about the problem and its consequences can sometimes be difficult for the person affected. That is when taking photos has a vital role in mediation between the inner and outer world. “Because creating a narrative implies putting the facts in order, distancing yourself a certain amount from the events and exploring what at some point was the opposite, what was destructive, with a vision of creation,” explained Tellez.

The workshop also showed them how to analyze photographs to understand how they have represented women throughout history, all of this at the same time that they touched on topics such as self-portrait, identity and the body.

“Now I see beyond. Instead of a simple photo, I see a story lived, a memory, a feeling and a way of drawing closer to myself,” said participant Daniela Obando.

A psychologist at the INAMU Regional Office, Zeidy Mata, explained that when the training processes incorporate fun techniques, such as photography, the participants begin a reflective process, obtain personal tools to face their problems and empower themselves.

Valeria, for her part, hopes at some point to be able to set up a program similar to the one she shared during the photography workshop, so that other women can share their experiences and knowledge.

She wants to get other women together and help them identify the types of violence they have experienced. “In this way, we are becoming more united. That is the most important thing, to understand ourselves a little more and free ourselves,” she explained.

Credits: Aranza Chavarria

Credits: Jimena Naranjo

Credits: Greys Zuñiga

Credits: Daniela Obando

Credits: Elcira Ruiz

Comments