The Costa Rica corporation Florida Ice & Farm and the U.S.-based Schwan Foundation controlled many of their multi-million dollar investments in the Papagayo Gulf Tourism Development from a web of shell companies created in tax havens.

Companies stashed their loans, earnings, and transactions in countries like the Bahamas, British Virgin Islands and the Cayman Islands that are not only out of reach to Costa Rica tax authorities, but also they are not charged taxes on these types of activities.

These three countries grant major privileges to those who have the financial power to create webs of companies and deposit their fortunes there. While not all the operations that take place are fraudulent (sometimes they take advantage of legal loopholes built into laws), they are often used to avoid or evade taxes: No one asks anything there.

From there, the first developments were orchestrated, such as the Four Seasons hotel and the Marina located in Papagayo, a land that belongs to all Costa Ricans and which the Costa Rican Tourism Institute (ICT) licenses to generate development and bring jobs to Guanacaste.

READ ALSO: The Seven Commandments that Sink Papagayo

One of the companies used by Fifco to administer its operations in the peninsula was London Overseas, registered in the Cayman Islands. Costa Rica’s tax revenue service, the General Taxation Department (DGT), found anomalies in Fifco’s income tax returns in which they sent money to this company.

In 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 the tax revenue service found that this money had been reported by Fifco as “capital contributions.” But the DGT considered these loans and that Fifco could have earned interest from these loans that they weren’t paying taxes on. As a result, they charged Fifco a ¢2.43 million colon fine ($4.3 million).

Asked by The Voice of Guanacaste, Fifco insisted that it “always obeyed the laws in the binding legal framework” and that they never received any fiscal benefits. The company’s executives declined to grant an in-person interview to The Voice of Guanacaste seeking further details and they didn’t respond with specifics to several of the questions sent via email to their press department. Rather, they sent a general statement.

For three months this newspaper investigated emails, transactions, investments and trading of shares among companies that controlled Ecodesarrollo Papagayo, documents leaked to the international press from law firms Mossack Fonseca and Applebay-Estera.

These leaks are part of the Panama Papers and the Paradise Papers, two global journalism projects led by the Pulitzer prize-winning International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ).

The investigation was also based on Fifco’s financial statement reports, which are public because Fifco is a publicly-traded company on Costa Rica’s stock market the Bolsa Nacional de Valores, and on Schwan’s U.S. tax returns filed with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). With this information we were able to corroborate the names of the companies that are mentioned in this investigation and those related to them.

The IRS records, in conjunction with the Paradise Papers, were used to uncover the main shareholder of Ecodesarrollo – the Schwan Foundation, whose investments in the Caribbean islands and in Costa Rica resulted in losses of almost $500 million.

READ ALSO: Learn the Story Behind Papagayo´s Largest Investor.

Fifco’s documents and the Panama Papers were used to develop this story.

The directors of the Schwan Foundation didn’t answer questions sent via email and to their office.

Two-Headed Octopus

Fifco and the Schwan Foundation were – up until 2012 and 2016 respectively – the largest shareholders of Ecodesarrollo Papagayo, the company they used in Costa Rica to channel investment funds from tax havens into the tourism development. In fact, it’s the largest licensee in the development. Through 2012, it owned 41% of the land.

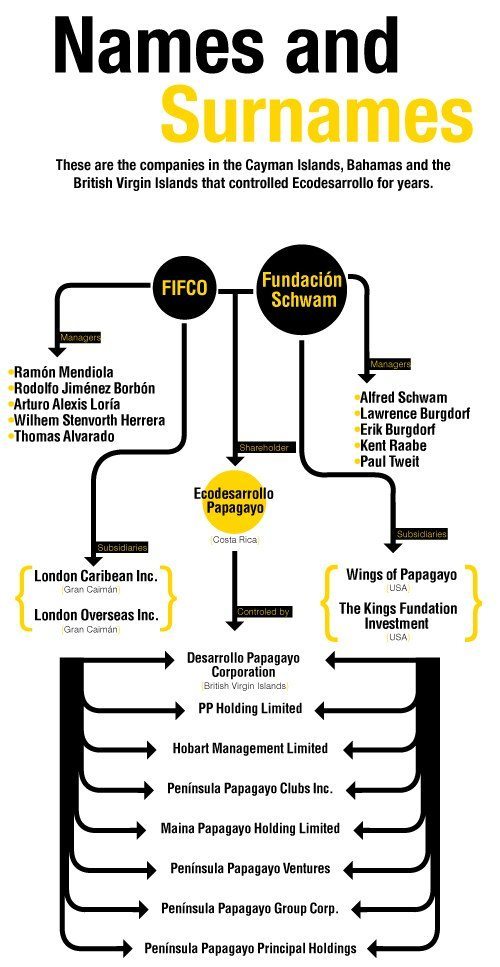

Instead of investing directly in Ecodesarrollo Papagayo, Fifco used two offshore companies created in the Cayman Islands as subsidiaries to do business with Schwan for at least eight years. Those companies were London Caribbean Incorporated and London Overseas Incorporated. The U.S.-based Schwan Foundation, in turn, used two affiliates in the U.S. called Wings of Papagayo and The Kings Foundation Investment Papagayo to channel its investments.

Through these companies, they created eight shell companies between 2000 and 2012 that were born in this order: Hobart Manage Limited, Desarrollo Papagayo Corporation, Península Papagayo Ventures, Península Papagayo Group Corp, Marina Papagayo Holding, Península Papagayo Clubs Inc and, to end its relationship, Península Papagayo Principal Holdings (See Chart “Names and Surnames”).

For each new line of business in Costa Rica, they would open a shell company either in the Bahamas or the Virgin Islands with, almost always, the same members on the boards of directors. Ecodesarrollo Papagayo S. A. claimed via email that the company does not know why its former shareholders chose a jurisdiction outside of Costa Rica to carry out its business.

Why did they use this method? “If you are hungry and there is a restaurant on the corner, you are going to cross the street, sit down and eat,” explained David Marchant, a U.S. journalist who specializes in offshore companies and who was consulted for this article. “What these companies do is take a taxi, go to the airport, get on a plane for 20 hours, get off, take a bus, take another plane, then do the entire return trip and enter through the kitchen door before finally sitting down to eat,” he continued.

For those of us that are paid every 15 days as our only means of living, it might sound strange that a company would create a subsidiary thousands of miles away to control, from there, its investments. It’s confusing precisely because it’s supposed to be; the strategy is to make some people dizzy while making things easy for others.

Hunger Games

It’s very common for companies the size of Fifco to invest large sums of money in well-known law firms, or even have entire departments to do their “fiscal planning,” which is the most politically correct way to call the exhaustive use of legal loopholes that allow large taxpayers to pay as little as possible. In other words, pay the lowest amount of taxes that they can.

Whether or not it’s ethical and, above all, whether it’s damaging or not for the countries is a discussion that has been sparked across the globe, including in Costa Rica. In fact, inefficiencies in tax collection (which the Finance Ministry admits to) and existing lax tax laws allow the richest to find alternatives that let them pay fewer taxes while the middle class has no other choice but to pay them because they are automatically withheld from paychecks or added into the price we pay for products we buy when we go to the store.

READ ALSO: Why should we tell the secrets of Papagayo and its shell companies?

“The less that big companies pay, the more consumers and salaried employees will have to sustain this country, which deteriorates the middle class,” explains Abelardo Medina, specialist from the Central American Institute of Fiscal Studies. “For a country to allow people to not pay taxes requires the administration to raise taxes on consumption in order to cover expenditures, and it’s at that point when all taxpayers are affected,” Medina said.

The game of tax havens is also a hunger game.

A Bad Calculation

In 2005-2006 and 2009-2010, the General Department of Taxation (DGT, entity in Costa Rica in charge of collecting taxes) found a smaller income tax payment than was owed because of an erroneous tax return filed by Fifco with its subsidiary in the Cayman Islands, London Overseas.

According to the DGT, a supposed monetary contribution to strengthen the capital of the company in the Cayman Islands was, in reality, a loan upon which Fifco could have received interest payments that they should have paid taxes on, but they didn’t.

Although the company took the case to Costa Rica’s administrative litigation court, insisting that this failure to pay is “what I add up as a difference of interpretation” it chose to pay one of the fines imposed by the tax revenue service, and shelled out ¢1.68 billion colons ($3 million).

In 2009-2010, the tax revenue service found the same “difference” on Fifco’s income tax return. This time, they charged Fifco ¢747 million ($1.3 million) in fines that, according to the latest report from 2017, was still in the appeals process in the administrative litigation court.

What was Fifco Using Companies in Tax Havens for?

Before 2012, the Panama Papers show that Fifco had at least $14.8 million worth of shares invested in the offshore company Península de Papagayo Ventures and another $6.8 million in another one called PP Holdings.

Despite the fact that Fifco was a direct shareholder in Ecodesarrollo Papagayo S. A. it hasn’t made a single direct investment in the company since 2005. It directed all the investments through its offshore companies shared with Schwan in tax havens, according to what is shown in their financial statements.

Fifco’s financial statements also show that the company also used its offshores to back loans from Scotiabank Cayman Islands to Ecodesarrollo.

What’s the problem here? Costa Rica has an income tax system in which you report only what you made within the country and therefore these kind of activities can be used to elude or hide operations that, in appearance, were done in other countries.

Rodolfo Jiménez Borbón and Ramón Mendiola are part of the Fifco board of directors that also signed share transactions made to Papagayo-related offshores. Thomas Alvarado, Arturo Alexis Loria and Wilhem Steinvorth are also listed as members of the board of directors.

Fifco quit doing business with the U.S. foundation in 2012 when it agreed to transfer all its shares in the companies that Ecodesarrollo Papagayo controlled to another company and, in exchange, received 311 undeveloped hectares (768 acres) in the northern part of the Peninsula, where they have already announced large developments.

In a statement made to the newspaper La Nacion in April last year, Rodolfo Jimenez Borbon explained that they formed the companies in tax havens because the main partner, the Schwan Foundation, wanted to do business in “neutral territory.”

Nevertheless, their financial statements reveal that this wasn’t the only aim. Until 2016, London Caribbean and London Overseas continued to appear as subsidiaries of the company.

Meanwhile, Guanacastecans and, above all, residents of Liberia continue wondering who really gained from Papagayo. The answer is in another paradise, thousands of miles from here.

This is How Investments in Papagayo were Moved Via Tax Havens

Have you ever stopped to observe the intricate work of a spider web? Imagine that in each knot of the web there is a name. Each name represents a corporation and three or four more threads spin out of it with other names at the end, names of people and corporations.

Expand your viewpoint and you will see how many names are repeated in each node and in each corporation. Then, transport that web to the Caribbean, locate it in the Bahamas, the Cayman Islands and the British Virgin Islands and you will see the most delicate and elaborate web of offshore companies in Guanacaste.

That web is what sustained the real estate development of the largest licensee on the Papagayo peninsula, Ecodesarrollo Papagayo, for at least 15 years.

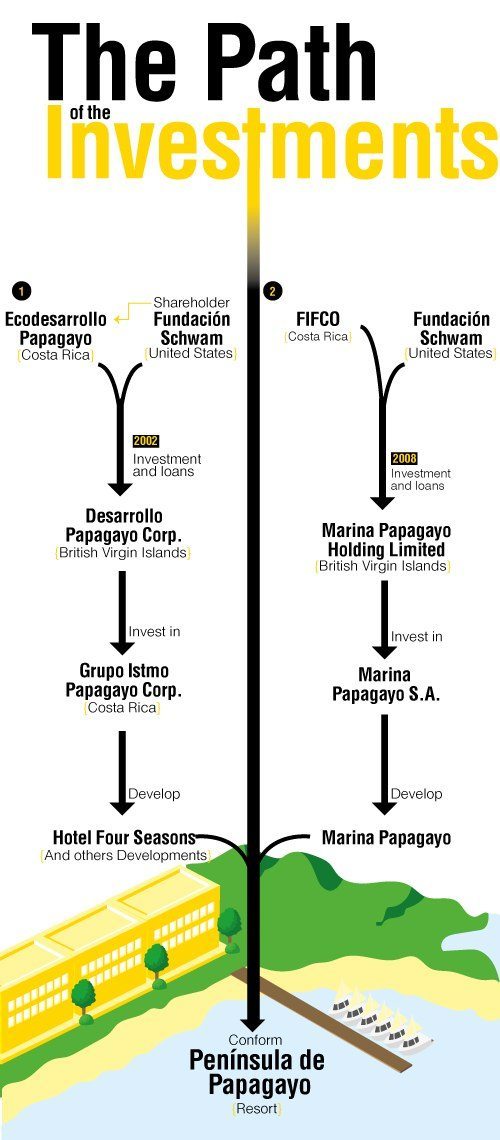

On September 21, 2000, a lawyer from Mossack Fonseca in the British Virgin Islands started to weave the fabric of this network. Ecodesarrollo Papagayo and the Schwan Foundation were the first shareholders of a new company that that same lawyer registered that day in the British Virgin Islands. It was called Desarrollo Papagayo Corporation.

They formalized it with few registered shares and, two years later, they injected it with capital so that they could dispense funds from there for the development of the Four Seasons Hotel on the Papagayo peninsula, according to a shareholder agreement leaked in the Panama Papers and dated November 1, 2002.

In order to do this, Ecodesarrollo contributed $21 million in capital and Schwan pitched in $12.6 million. Schwan would also grant a loan to this new company for an additional $8 million to be paid by a third partner called Four Seasons Hotel, registered in Barbados (another tax haven).

Desarrollo Papagayo Corporation should use all these capital injections strictly for buying shares from Grupo Istmo de Papagayo, a company created in Costa Rica to build the Four Seasons Hotel.

In 2002, Schwan and Ecodesarrollo stopped appearing as shareholders of Desarrollo Papagayo Corporation as well as the rest of the companies. In its place its subsidiaries are the ones that make the decisions, although the executives that sign off on the decisions are still the same people. Sometimes they appear as having power of attorney and other times as presidents, but their names repeat infinitely in all the documents.

After the construction of the Four Seasons Hotel, the marina followed. For the marina an offshore company was also created in 2006 called Marina Papagayo Holding Limited, which controlled the shares. Later, they created others for other developments and services.

In large part, the companies that were created bare the name of Ecodesarrollo’s CEO, Alan Kelso Machado, as having general power of attorney or unlimited general power of attorney. Via email sent through the company’s Senior Vice-President Manuel Ardon, his lawyers responded that these transactions were never relevant for Ecodesarrollo “from the operational, fiscal or regulatory point of view.”

Fifco quit being a partner of Ecodesarrollo in Costa Rica in 2012. At the same time, in the British Virgin Islands, it transferred all its shares in the companies that controlled Ecodesarrollo to Wings of Papagayo (Schwan’s subsidiary) through the creation of a new offshore, Peninsula Papagayo Principal Holding.

In 2016, Gencom, a powerful, global firm in the hotel industry, bought all of Schwan’s shares in Ecodesarrollo. A walk by its land shows the impact that the acquisition had on the tourism complex: there are men everywhere working to improve the roads and the Four Seasons has been closed for months for remodeling, as well as the Hyatt and other developments that Gencom bought. Investigation produced by The Voice of Guanacaste in alliance with:

Comments