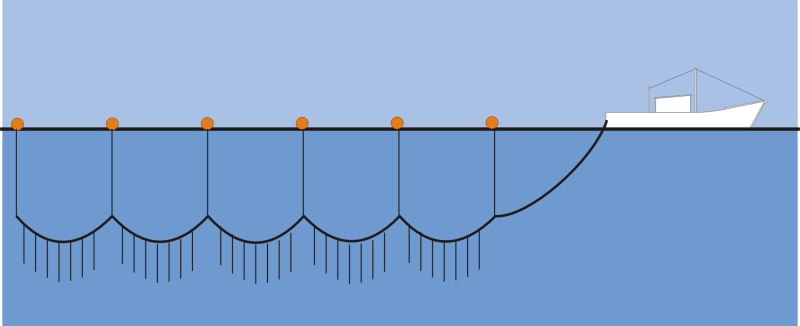

The second-most-common catch on Costa Rica’s longline fisheries in the last decade was not a commercial fish species. It was olive ridley sea turtles. These lines also caught more green turtles than most species of fish.

These findings and more, reported in a new study in the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, indicate that the Costa Rican longline fishery represents a major threat to the survival of eastern Pacific populations of sea turtles as well as sharks

The researchers argue that time and area closures for the fisheries are essential to protect these animals as well as to maintain the health of the commercial fishery.

The research was conducted by a team from Drexel University, the Costa Rican non-profit conservation organization Pretoma and a U.S. non-profit working in Costa Rica, The Leatherback Trust.

The researchers used data from scientific observers on longline fishing boats who recorded every fish and other animal caught by the fishermen from 1999 to 2010 and the locations of the captures and fishing efforts. Those data provided the basis for a mathematical analysis of the fishery resulting in maps of geographic locations and estimates of the total number of captures of sea turtles in the entire fishery.

The most commonly targeted fish, mahi mahi, is one of the most common species caught in the Costa Rican longline fishery.

But the researchers were surprised by their finding that olive ridley turtles, internationally classified as vulnerable, were the second-most-common species caught.

They estimate that more than 699,000 olive ridley and 23,000 green turtles were caught during the study period (1999 to 2010)

Although about 80 percent of captured sea turtles are released from longlines and survive the experience, at least in the short term, long-term impacts are not yet adequately measured.

“It is common to see sea turtles hooked on longlines along the coast of Guanacaste in Costa Rica. We can set some free but cannot free them all,” said Dr. James Spotila, the Betz chair professor of environmental science in the College of Arts and Sciences at Drexel. “The effect of the rusty hooks may be to give the turtles a good dose of disease. No one knows because no one holds the turtle to see if its gets sick.”

Spotila, a co-author of the study, has been studying sea turtles on the Pacific coast of Costa Rica with colleagues and Drexel students, for 23 years.

The researchers also noted that even a few deaths of reproductive females may have a significant toll—particularly when longline operations are held in shallow waters of the continental shelf close to nesting beaches. They reported that declines in olive ridley nesting populations in Ostional, where massive synchronous nesting occurs, were associated with these captures.

Comments