Miguel Fajardo Korea didn’t have much growing up, but he’s convinced that education let him carve a path of improvement that has led him to where he is today.

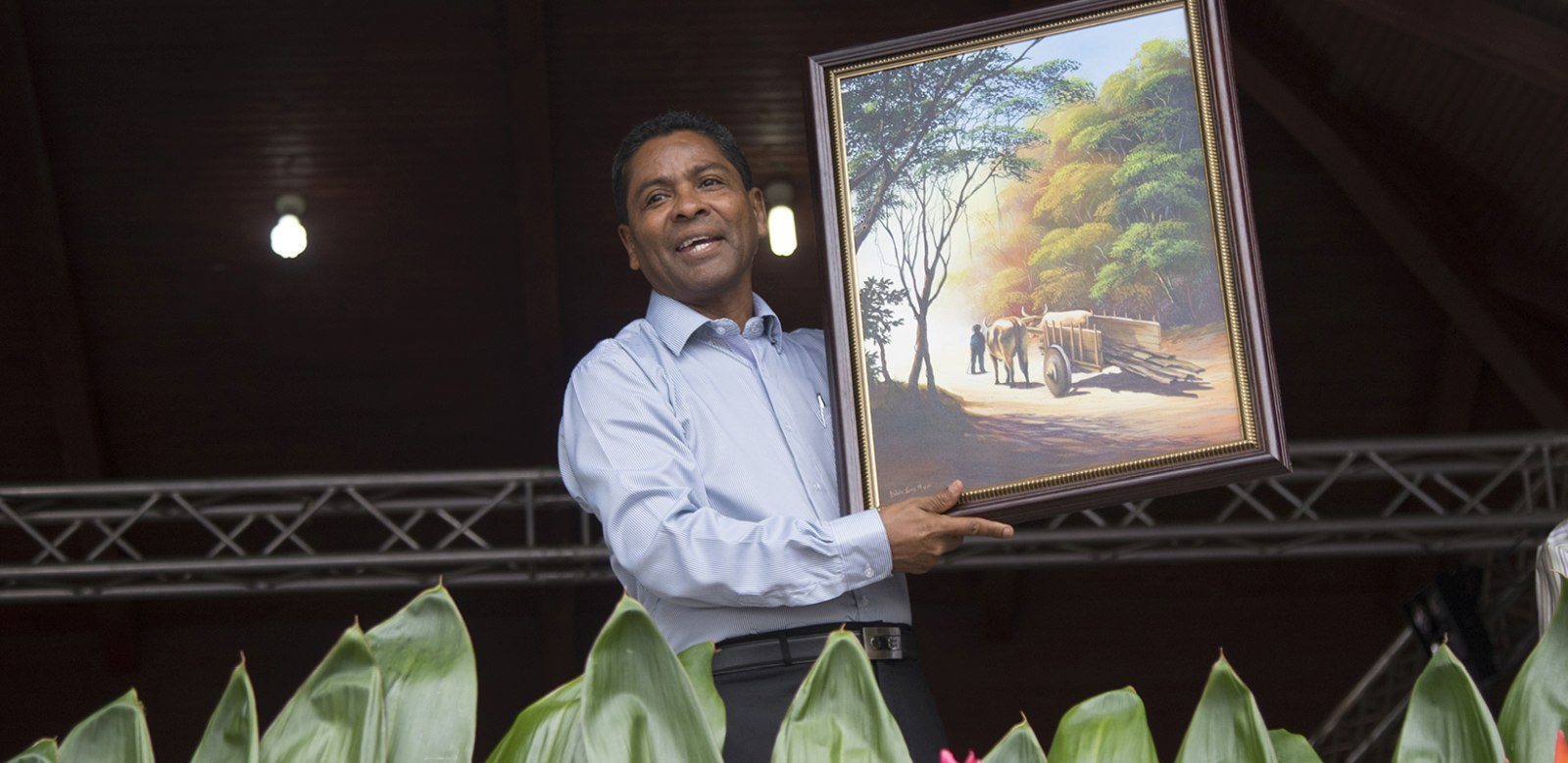

This 61-year-old Liberian is the winner of the La Gran Nicoya 2017 Prize, the highest cultural honor that Guanacaste bestows upon its citizens.

The award recognizes work that Fajardo Korea has done over more than 40 years, voluntarily and independently, as an educator, writer, editor, researcher, and cultural promoter.

Fajardo has written 32 books and 750 articles in newspapers and magazines; he’s worked in education for 32 years; he’s won 18 awards and distinctions; and he’s participated in 40 activities in literature, culture, and academics. “And I still have lot of energy and desire to continue working,” he says.

Overcoming everything

Fajardo was born on April 5, 1956, in Liberia. His father, Miguel Sánchez, was a zonero, which is what they called men who traveled from Guanacaste to the banana-producing zone on the Atlantic to work as laborers on the farms.

“My father never saw me because three months after I was born he lost his sight in an accident and he was blind for 47 years.” This disability kept his father from working, so his mother, Ramona de Jesús Fajardo, had to battle to help Miguel and his six siblings get ahead.

“She worked hard as a maid, day and night, in houses, hotels, rooming houses. She was a brave woman and died young at 55.” His admiration for his mother was so strong that adopted her maternal last names.

In spite of economic hardships, young Miguel always felt motivated to get an education.

“Education is a weapon of social mobility,” he says.

He went to elementary school at Asención Esquivel, in Liberia, and fondly remembers his third grade teacher, Rose Marie Nassar, who one day told him that he had a talent for writing. “And that got me thinking.”

When he learned to read he became his father’s seeing-eye, he says. “Through reading, I guided him through a world that he couldn’t see. I read him newspapers, books. We always communicated, in spite of his blindness.”

In high school he was encouraged by the teacher Hilda Camacho to continue along the path of literature. He did, getting his bachelor and master’s degree in Linguistics and Literature from the Universidad Nacional (UNA).

His literary debut was in 1981 with not one, but three books: the collections of poems Urgente búsqueda (Urgent Search), Estación del asedio (Siege Season), and Extensión del agua (The Water’s Expanse). The second book won the Young Creation award that year.

Starting then, poetry became his favorite literary genre. Today he has written 14 books of poetry.

Fajardo’s books of poetry

- Nosotros del mundo, (España, 1983) (We of the World, Spain, 1983)

- Parte del fuego (República Dominicana, 1983) (Part of the Fire, Dominican Republic, 1983)

- Solo la noche (1989) (Only Night)

- Las puertas del sol, (1992) (The Doors of the Sun)

- Margen del sueño (2000, Premio Jorge Volio) (Margin of Sleep, Jorge Volio Award)

- Travesías (2008) (Journeys)

- La demora más larga (2012) (The Longest Wait)

Fajardo was also the director of four magazines and has been editor of 28 annual cultural supplements for the newspaper Anexión, in Guanacaste.

Books dedicated to Guanacastecan characters

- Héctor Zúñiga: palabra y canto (1993) (Héctor Zúñiga: Word and Song)

- Sacramento Villegas: canción en el tiempo, (1994), (Sacramento Villegas: Song in Time)

- Medardo Guido: cantares de la pampa (1996 y 1997) (Medardo Guido: Songs From The Pampa)

- Los caminos unánimes de Ciro Montero (2009) (The Unanimous Roads of Ciro Montero)

- Jesús Bonilla… dimensiones (2011) (Jesús Bonilla… Dimensions)

- Lía Bonilla: caminante de Guanacaste (2012). (Lía Bonillla: Guanacaste’s Wanderer)

- Otras lunas: presencia femenina en la literatura de Guanacaste (1892-1996) (Other Moons: Female Presence in Guanacaste’s Literature 1892-1996)

For him, culture belongs not to the few, but to everyone. As vice president of the Guanacaste Literary Center, founded in 1974, he showcases young authors’ works.

“The first Saturday every month we hold critical-reading sessions to exchange knowledge. Unlike some workshops in the Central Valley where participants follow the style of a writer-leader, here everyone is owner of his own style.”

His other passion is to educate. He was a teacher for 34 years. He went from the Laboratory High School in Liberia to the Night High School in Liberia to the Universidad Nacional as a professor. Because of his deeply felt convictions, he’s bothered by some teachers who don’t show the same level of commitment.

“I don’t see that passion in new professionals in educations. They’re disinterested, apathetic, and this makes for unmotivated students. Educators should become examples to follow, and not just “paycheck” educators”, he says. He is testimony that just one teacher who is committed to education can change at least one life.

Comments