Since the pandemic hit Costa Rica, Manuel Agüero, coordinator of the HIV Project of the Lutheran Church for the country, begins and ends his days reviewing a WhatsApp chat with 150 people who have HIV. Agüero created the group to provide information and emotional support to those who, in the midst of restrictions due to the health emergency, face difficulties in obtaining the antiretroviral drugs they need to stay alive.

When the HIV virus enters the body, it invades white blood cells, destroys them, and multiplies. This weakens our defenses, and when HIV patients develop symptoms and the infection progresses, they can present with AIDS, the most advanced stage of the virus.

That’s why antiretrovirals are so important. Not only are they capable of slowing the spread of the HIV virus, but they also reduce the chances of getting and transmitting an infection.

Since March 6, when the first case of COVID-19 was detected in Costa Rica, dozens of HIV patients have lived with the anguish of being at greater risk against their will. HIV therapy involves taking a combination of medications daily at a specific time. Not doing so means risking that the virus replicates.

However, only 1.3 million of the 2.1 million people who were diagnosed as HIV positive in Latin America have access to treatment. This situation is being aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a journalistic investigation done by PODER and Salud con Lupa, in alliance with regional media.

What is happening in Costa Rica? We analyzed the situation in this report, published jointly by La Data Cuenta, The Voice of Guanacaste and UCR Interferencia de Radioemisoras .

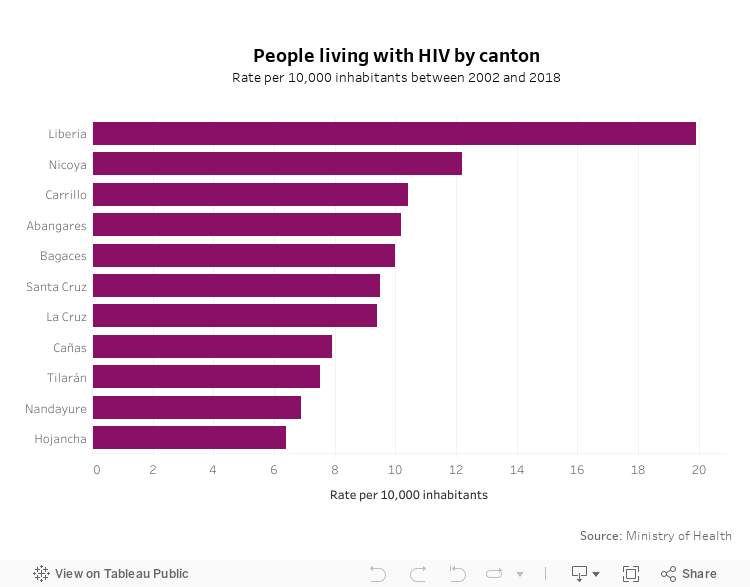

In Costa Rica, 11,076 people have been diagnosed with HIV, according to 2019 data from the Ministry of Health.

Eighty-five percent of them receive treatment from the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS). Not everyone gets it because some don’t start therapy, quit getting treatment or have severe side effects that prevent them from continuing.

When the pandemic started, CCSS fast tracked a plan that lets patients pick up their medications in 788 Ebais clinics and 96 health areas. A system was set up for filling prescriptions electronically by phone or online, as well as home delivery of medicines for chronic patients.

These measures were put in place to avoid crowding in national hospitals and thus reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19. However, this strategy has not worked for everyone. Medicines are not arriving on time to all health centers and Ebais clinics as planned.

According to Agüero, some patients receive their medications up to 15 days later than what their prescription indicated. “These people break down emotionally because being without their medications is a death sentence for them,” he related.

To try to calm their anguish over this situation, some go to bed very early and sleep as many hours as possible. “It’s their way of protecting themselves from the death that is lurking outside,” Agüero remarked.

Rodolfo Leiton has been living with HIV for two decades. Although he hasn’t had any problems getting antiretrovirals supplied to him by the Costa Rican Social Security Fund (CCSS), he knows people who have faced delivery delays. As a counselor for the Esperanza Viva (Living Hope) Association, he works with these patients to help them cope with the difficulties brought into their lives by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the photo, he is with his mother, Haydee Hernandez, who is his main support. Credit: Mayela LopezPhoto: Mayela López

Several Groups Affected

Why has medication distribution become so complicated? Spokespeople for the CCSS indicated that this happens in certain health areas and Ebais clinics because the personnel in charge don’t request the shipment of medications for the corresponding hospital on time.

According to Antonio Solano Chinchilla, head of Infectious Disease Services for the Rafael Angel Calderon Guardia Hospital, these delays are not justified because dispatch from pharmacies to health centers can be done in 24 hours.

There are more obstacles to accessing medicines outside the Greater Metropolitan Area, clarified Rosibel Zuñiga, president of the Esperanza Viva (Living Hope) Association (ASEV).

Rosibel Zuñiga directs the Esperanza Viva (Living Hope) Association, which has been supporting people with HIV in Costa Rica for 20 years. During the health emergency, this association has advised people who are experiencing delays in their medication deliveries. Zuñiga and her team facilitate paperwork, renew or obtain medical insurance and even apply for a little financial support for transportation to medical centers if necessary. Credit: Mayela LópezPhoto: Mayela López

The CCSS strategy hasn’t taken into account the needs of patients in indigenous communities, areas far from the greater metropolitan area and in poverty situations, with limited access to the internet and to cell phone use, for whom it is very complicated to figure out how to request a prescription electronically or how to process shipment of medicines to their home or to the nearest Ebais.

“We know of cases of people cut off because they don’t have money to recharge their cell phones or they have tried to get information by phone and can’t wait long because their remaining credit runs out, so they go to hospitals and are told that they can’t give them their medicines there,” Agüero pointed out.

Gloria Terwes, coordinator of the CCSS HIV-AIDS and Sexually Transmitted Diseases Program, indicated that despite institutional efforts, the health emergency has made it difficult to care for patients with HIV and other pathologies.

However, she stated that HIV cases “have been well cared for.”

Migrants, especially refugees and those who are undocumented, also have problems getting access to antiretrovirals since some entities only deal with them by mail. “Foreigners come already diagnosed, but with a low dose of medicine and they have to wait longer to be taken care of,” Manuel Agüero commented.

According to data from the Ministry of Health Directorate of Surveillance, as of 2017, there are more than 300 migrants on antiretroviral therapy in the country.

One of them is Maritza Gonzalez * (name changed to protect her identity), who arrived in the country from Cuba in 2019 at the end of September with enough medication for five months. She believed that would last her while she was processing her refugee application, work permit and state health insurance.

In the middle of that process, COVID-19 broke out and she had to wait five months to receive treatment through CCSS.

At Hospital Mexico, they gave me an appointment for April 26, but later they called me and changed it to May 20. On the day of the appointment, they did tests on me, took x-rays and gave me pills for anxiety. I had to wait another month for the antiretrovirals. I endured five months without them! The day they gave them to me it was almost like a party,” González recalled. For other migrants, the antiretroviral odyssey continues.”

The 2019 reform of the General Law on HIV-AIDS authorizes CCSS to treat foreigners under a series of conditions: having legalized their status, on a humanitarian or refugee visa status, and having identification documents.

However, if a person who doesn’t meet these requirements comes to the emergency room with an acute condition, social security will assist them, clarified Gloria Terwes from the CCSS.

CCSS Says There’s No Shortage

Organizations such as the Lutheran Church and the Esperanza Viva Association affirm that requests for help from patients who lost their jobs have increased and, since they can’t keep paying their medical insurance, they have issues continuing their therapy.

In other cases, patients’ state insurance expires, making it difficult to get treatment, indicated Antonella Morales, director of Transvida.

However, the General Law on HIV-AIDS and the Constitutional Court jurisprudence establish that medication can’t be interrupted due to late payment and must be guaranteed to poor or indigent patients, regardless of nationality.

Dr. Terwes recognizes these rights but reminds people that patients have obligations as well. For example, she emphasized that if they stop paying for insurance, health services can’t attend to them immediately until each case is studied. They will be provided treatment but will need to make a payment arrangement with the CCSS.

Costa Rica has a three-month reserve to deal with a possible world shortage of antiretrovirals and is processing orders from manufacturers in advance.

“There are sufficient inventories to cover approximately three months of consumption in most cases. Currently, there are no shortages. However, there have been delays in deliveries, influenced by the COVID-19 emergency worldwide,” the CCSS Logistics Management of the Provision of Goods and Services Directorate Programming Sub-Area responded.

Although there is no risk of shortages, the fear of running out of the medicine they need causes many patients to relive the anguish they experienced when they were first diagnosed with HIV.

The pandemic has taken us back to that moment when we feared death. In my case, in addition to having lived with HIV for 20 years, because I am hypertensive and I fear how my body will react,” confessed Zuñiga, from the Esperanza Viva Association.

Each day, Zuñiga overcomes her fears to provide support to the more than 100 people who make up her organization and to continue working with them to defend their rights. This has been the case since 2001, when ASEV emerged as the first association of women with HIV in the country, and now she is fighting to carry on despite the pandemic.

“I endured five months without antiretrovirals”

I was diagnosed with HIV very young, at 16 years old. I have been living with this for 20 years and the treatment I received in Cuba was what kept me on standby my whole life.”

Maritza González agreed to tell us about her experience on the condition of anonymity. She arrived in San Jose in September 2019 with the help of a coyote (someone who smuggles people across borders), and asked for asylum.

“In my country, you work and work and you don’t see results, so I decided to sell everything in the house and I got a visa to go to Nicaragua with the intention of crossing overland to Costa Rica,” Maritza related.

“My hope was to get health insurance, medication and a job as soon as possible. For all of that, I had to do paperwork and wait. I brought treatment for five months, but it ran out in February.”

By mid-March, when the state of emergency due to COVID-19 was declared in the country, she had already gone almost two months without taking antiretrovirals and the situation became more complicated. She was very nervous.

“I saw the news about all the dead in the world and I decided to go to Hospital Mexico to try to get antiretrovirals. That day, I found out that the state had already insured me.”

Maritza remembers that they gave her an appointment for April 26, and later they changed it to May 20. “That day they did tests on me and they only gave me pills for anxiety. They finally gave me the antiretrovirals in early July. I was very scared. I was scared the whole time.”

“I became very desperate,” she said, when they changed the appointment and told her she had to wait. “I lost an unusual amount of weight, I suffered a lot of headaches, I imagine from thinking so much about what the lack of medications could do to my body if I got COVID-19.”

Comments