Two police officers look for clues to solve a femicide (murder of a woman because she is a woman) in a dusty, isolated and rough town. But it won’t be easy. The crime occurred in a cross-border community, in that gray area where one country ends and another begins.

They have to solve the case in a territory that doesn’t trust authority figures like them due to a history of neglect from governments. Although it sounds like a Wild West movie, the entire story takes place in Guanacaste.

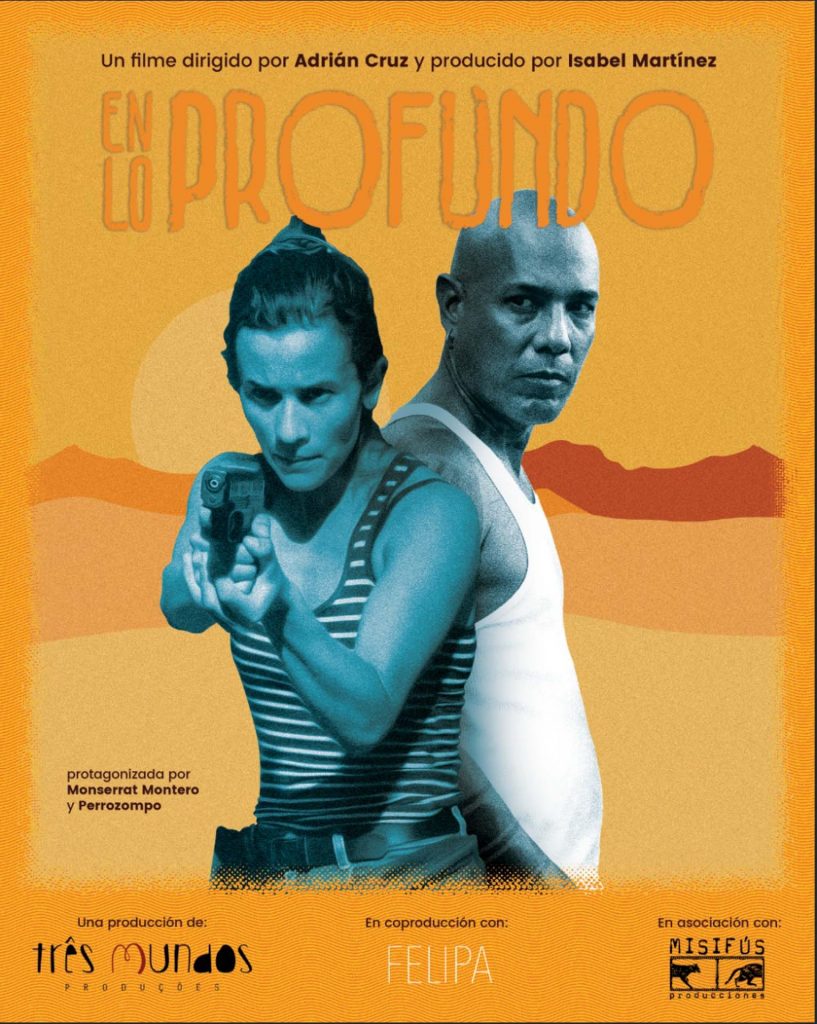

En Lo Profundo (In the Depths) is a feature film and a fictional crime thriller inspired by the feature article The unpunished femicide of Darys Mora. The article was published as part of “The Drawn Border,” a binational investigation carried out jointly by The Voice of Guanacaste, Interferencia de Radioemisoras UCR and Confidencial. In 2020, this series of reports received the Jorge Vargas Gené Award, awarded by the Costa Rican College of Journalists.

According to the movie’s director, Adrian Cruz, the narration of the story of Darys Mora in the article has a very cinematographic character.

The way they worded the article was very, very vivid. It’s not the typical article or journalistic chronicle that is like very dry. Rather, it really transmits many images,” explained Cruz.

En Lo Profundo is in the pre-production stage, but it already has big names within its cast.

Actress Monserrat Montero, who has participated in films like Miguel Gomez’s Amor viajero (Traveling Love) and El regreso (The Return) by Hernan Jimenez, will play detective Amaranta Villalobos. And Perrozompopo, a Nicaraguan singer-songwriter known for songs like Quiero que sepas (I want you to know) and Entre remolinos (Between whirlpools), will play the character Sebastian Toruño, an experienced Nicaraguan police officer.

Actress Monserrat Montero plays detective Amaranta Villalobos in the feature film. Photo: courtesy of the production department.

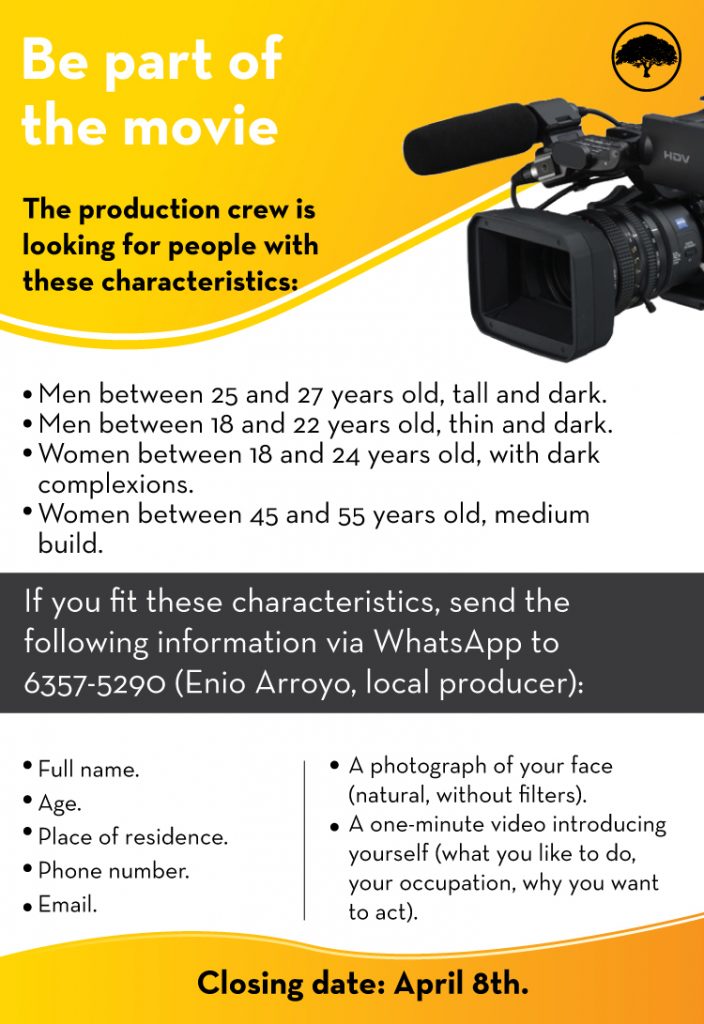

Right now, the production crew is looking for people from the province willing to bring to life the rest of the characters. The Voice of Guanacaste spoke with Cruz about the casting details and his experience debuting as a feature film director.

The Voice: What did you see in Darys’ story that made you think about turning it into a movie?

Adrian Cruz: (The issue of) gender violence is clearly of high social relevance. I think that now more than ever, it’s on the national scene, due to the political situation in which a candidate has a conflict and the recent march on March 8 with a super large presence of women demonstrating due to that other pandemic.

We continue to have cases of femicide in different parts of the country and there is no end in sight. This particular one is circumscribed in a geography that gave it an additional disadvantage; that is to say, it gives it a higher probability of impunity. The fact that it was a region that was not only rural, remote, but also cross-border. So that seemed to me a very traumatic situation and that lent itself to recapturing it. In this case, it was fiction, but respecting that spirit of the original story. And from there, the project started gaining strength. It wasn’t just to recapture a forgotten territory, but to address a problem that is more relevant than ever.

TV: Why do you think that fiction is a good tool to talk about this story?

AC: The police genre and crime stories have a great media impact at the moment. For example on Netflix, in the number of movies of this genre that they have in their programming and not only of the crime fiction genre, but also documentaries. It’s a subject that the general public is interested in and we, obviously, as a production team are interested in connecting with a wide audience, not just for commercial reasons but also to position the subject we’re talking about.

Fiction allows more creative freedom than documentary. The documentary must always be anchored to the original case and it’s a case that still has many gaps at the level of investigation. It remains unsolved, which limits the possibility of giving it closure under the documentary genre, like a closure that would satisfy the public. On the other hand, fiction does allow much broader creative freedoms. We can close the narrative.

En Lo Profundo (In the Depths) 2022 poster

TV: You decided to keep the nickname of the main suspect in the femicide: “El Ñambo.” Why?

AC: I found it very, very memorable. It’s a unique name, since it’s a nickname that’s easy to recognize: two syllables and in a very local terminology. As I understand it, the ñambo is a fruit from that area of the Pacific dry forest. And they gave this guy that nickname. I don’t know if it’s the nose or something like that on his face that looks like that fruit. The guy is on the run, according to what I learned. They still hadn’t been able to locate him. But I thought it was kind of an interesting wink to the original case. Maybe it can provide a clue so that someone else also wants to get interested in the original case.

At the level of how it sounds and at the memory level it worked very well and that notion that it’s not the person’s name but that it’s a character endowed with all the aura of a fugitive who’s hiding, then his supposed essence as a person was erased and it makes him an archetype of a dangerous suspect. And in the movie, part of the investigators’ journey is to discover the real person behind this character.

TV: Do you plan to look for a good part of the talent for the movie here in Guanacaste?

AC: Yes, that’s the idea. With the exception of the two main protagonists, we hope that all the characters that appear in the film are from that area, are from Guanacaste or even of Nicaraguan origin. Because we have that mix of both citizenships and that’s also for two reasons: for a matter of ethics, to be faithful to the spirit of the situation that gave rise to the idea of the movie and to be faithful to the geographical area and the people who inhabit it. And on the other hand, it’s a question of authenticity. There are physiognomies, there are ways of dressing, there are ways of speaking that it’s very difficult to fake, that it’s very difficult to reproduce. For the proposal to really look credible, you have to turn to people who are authentically from there.

TV: Where will you film it and how do you plan to integrate the communities in which you’re going to work?

AC: That’s part of the same proposal to be faithful to the region, right? It’s not that we’re necessarily going to film it in the same town as the original case, because we have an idea of a dry area aesthetic, more typical of the Northwest area. And in that sense, part of the idea of the trip that we’re going to do now in April is to also look for the location, because we need this town that’s very neglected, very rough, with gravel streets. Looking for something very specific on a visual level and with many vacant lots, with hills, pastures, houses that are very isolated from each other.

Director of photography Ernesto Fernandez Telleria while recording the pilot with actress Monserrat Montero. Photo: courtesy of the production department.

The idea is to get a location by the time the movie is going to be made and live there for the duration of the production. And that also implies that the community is involved beyond just the characters or extras, but also that the accommodation and meals are with local people, that the movie also allows the funds we obtain to be distributed a little in those communities and in the businesses they have.

TV: How do you think the movie can address, for example, realities like that of Guanacaste and other rural areas of the country?

AC: Many times we filmmakers are from urban areas and we end up making stories about those realities. But it’s equally interesting to address what we don’t know.

In our case specifically, we’re mainly interested in giving that notion of real neglect that exists in communities that don’t have police stations, or police, or institutions that are called to address the situation of disadvantaged people. Where they are most needed is precisely where they have the least geographical presence.

It works as a kind of metaphor like the Old West, these super far away towns where they have problems of access to telecommunications, problems of access to public transportation and everything that this entails in case of having to go somewhere to do bureaucratic, banking, immigration paperwork, health.

So the idea is that this environment where we film should reflect this isolation. That it conveys to the public that feeling of communities that are literally neglected by the authorities, by the State, as a way of approximating those other realities that rarely appear on the screen, but it’s also necessary that they have a leading role.

En lo profundo is in the development stage, where the proposal is planned out at the level of financial viability and the narrative content. The project has already received recognition and funds from the UCR University Foundation, Development Banking and the Ibermedia Program, an international intergovernmental fund that supports the best film projects in Ibero-America.

Comments