“One of the biggest crisis in the country isn’t the economic crisis. It’s the moral and spiritual crisis people face. There is a spiritual and moral void that the city, not the church, must satisfy. The city provides resources from all Costa Ricans. We should a portion of it in all municipal governments in order to strengthen values.”

Pablo Guevara, second deputy mayor of Cañas who made this statement, is a pastor at the Oasis de Esperanza church and brother-in-law of National Restoration congresswoman Mileydi Alvarado, the first openly evangelical congresswoman to represent Guanacaste. In 2017, he and other evangelical churches in the community pushed to use taxpayer funds for 200 children and teens in Cañas to attend an evangelical camp, La Montaña Christian Camp, in San Ramón, Alajuela.

La Montaña Christian Camp’s purpose is to “train youth leaders for radical, aggressive evangelicalism” according to their website. It’s a typical evangelical camp, says Alberto Rojas, sociologist and theologian at the National University (UNA). “It’s a way to evangelize youth so they accept Christ and become evangelical Christians.”

In a phone interview, Guevara confirmed that La Montaña held activities aimed at “promoting teamwork and Christian values” and that local companies sponsored them, taking evangelical and catholic kids to the camp. He said that they were kids who had never had an opportunity like this before. “It was really exciting for many of them.”

[Help us continue investigating the stories that matter to you. Donate today].

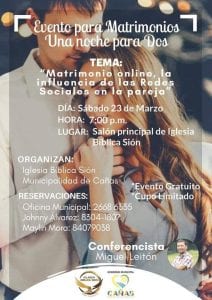

March 23rd, Cañas Municipality hosts an event for couples, organized along a baptist church.

The City of Cañas spent ¢6.5 million (some $10,800) on the camp. The deputy mayor says that they also sponsored other activities with evangelical churches to strengthen families and marriages, where everyone is accepted, including a same-sex couple. “That’s the idea,” he said.

In a province where 25% of voters are evangelical, what Guevara does is just one example of the influence that pastors and evangelical leaders who get involved in local politics have.

To show the relationship between evangelicalism and local politics, The Voice of Guanacaste, in alliance with Semanario Universidad, interviewed local and national leaders of religious parties – whose social base is a religious group – pastors that have or had ties to the National Restoration party in 2018 and academics and specialists who have studied the relationship in the country.

While some national leaders try to make visible their rejection of using the church as a political platform, in Guanacaste the lines are much more blurry, which, for now, doesn’t seem to follow a pattern. In our reporting we found an evangelical candidate who pushes for strengthening the traditional family between a man and a woman and church leaders that prefer to break ties completely with politics despite having participated in 2018 in the campaign of former presidential candidate Fabricio Alvarado, the first evangelical politician that reached a runoff election for president of Costa Rica.

The stories are part of a collaborative investigation with the support of the Columbia Journalism Investigation called Transnationals of faith (Transnacionales de la fe in Spanish), which seeks to explain the influence the evangelical church has in Latin American politics. The investigations reveal that evangelicals often have a strong influence in public policy on topics ranging from same-sex marriage and other rights for people of diverse sexual backgrounds, sexual education, in-vitro fertilization and legal abortion, as well as opposition to the separation of church and state (which seeks to eliminate religion from the constitution. Costa Rica and Guanacaste are no exception.

The Political Spoils of the Church

President of the Costa Rican Evangelical Alliance (AEC) Rigoberto Vega, said in an interview with The Voice of Guanacaste that he opposes evangelical leaders getting involved in electoral politics.

After economic scandals and political breaks in National Restauration, the Evangelical Alliance president says he wants his church to walk away from partisan politics.

“I am concerned about the participation of the church, of leaders in partisan politics. That’s something we shouldn’t get involved in, much less give our resources, infrastructure, pulpits or services to,” he said.

According to Vega, the alliance’s official statement is still being drafted, but he is already visiting communities to speak with pastors and other leaders and inform them of the alliance’s stance.

The AEC, according to Vega, incorporates 85% of the 4,000 evangelical churches in the country. In 2014 and 2018, the Supreme Election Tribunal sanctioned the organization for using their platform to seek votes for candidates that promoted Christian values.

He visited Nicoya in May and constantly publishes on Facebook that he is in constant contact with church leaders in all areas. He’s not the only influential pastor that has given this type of declaration.

In an interview with Semanario Universidad, pastor Carlos Chavarría, leader of the G 3:16 church, said he was the one to put members of his church in Fabricio Alvarado’s campaign, but now thinks that he disagrees with the idea that “a Christian pastor has a political calling.”

Renowned business owners, professionals, politicians and athletes have spoken with Chavarría, seeking advice, including Ottón Solís and former presidents such as Óscar Arias Sánchez and Miguel Ángel Rodríguez. Saprissa coach Walter Centeno and congressman Carlos Avendaño have also come to him.

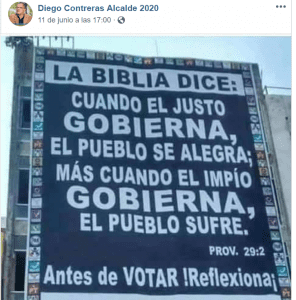

Hundreds of kilometers from the of these San Jose leaders, National Restoration candidate Diego Contreras spoke with The Voice of Guanacaste. Sitting on a bench in a bakery, he explains his vision for the relationship that should exist between religion and electoral politics.

Picture taken from Diego Contreras’ official Facebook

“Churches are autonomous. There is a leader who defines things. For example, I can speak with a pastor. I can speak with the brothers, go to a church and have them invite me to preach. And if the pastor wants, if he says to me ‘if you want you can announce your candidacy for mayor’ then I can announce it. Nothing more. I can’t bring campaign signs into the church or anything like that. I can announce that I’m a candidate for mayor, that’s not a sin nor does it harm the church’s image nor mine,” he says.

Contreras is pastor of an evangelical church in Villareal, Santa Cruz and says that he has never given a sermon aimed at fortifying his political campaign, nor will he do it.“It’s prohibited by the party,” he says. But he has no reserves about continuing as pastor, regardless of whether or not he is elected mayor. “If you made me chose between God and city hall, I would leave city hall behind and go with God.”

He was one of the first candidates in the province to announce his interest in politics and says that he has the blessing of evangelical leaders and his boss in the province, National Restoration congresswoman Mileydi Alvarado.

In fact, the congresswoman thinks religious leaders have every right to get involved in politics. In her view, having a religion doesn’t have any influence beyond the “principles and values” that her party professes.

Alvarado, for example, supports reforming the constitution in order to protect human life from conception and declare a national pro-life day. She also supports the bill for religious freedom and strengthening the Obras del Espíritu Santo association with funds from the Social Protection Board.

Evangelical pastor and singer Diego Contreras says he doesn’t have any politic experience, but that God’s going to give him the wisdom to lead a local government.

In Liberia, business manager Jeffry Esquival was named last June as a candidate for National Restoration for the 2020 campaign. While he’s not an evangelical leader, he attends an evangelical church. He says that religion will only influence is “principles and values” like strengthening family and being “inclusive” of all religions.

When I refer to inclusive, I refer to what is established in the constitution of Costa Rica that says men and women make up the family. That’s as far as I can go because I respect the laws of Costa Rica,” he says.

In 2018, when Fabricio Alvarado’s campaign boomed, pastors across the province backed the candidate.

One of them was Nicoya’s Oasis de Esperanza pastor Marco Quesada, who now prefers to detach himself from all political commentary and says that he was only involved in Fabricio Alvarado’s campaign for a month and then left because of the amount of work he had at his day job.

“I did it to support the pastors federation in Nicoya,” he says. His colleague, pastor Anabelli Madriz, led the National Restoration campaign in the canton and now leads it for the New Republic party, led by Fabricio Alvarado after his separation from National Restoration. She preferred not to give a statement because the party is finalizing registration details with the Supreme Elections Tribunal.

How it All Started

Religious parties had never earned more than 1% in national or cantonal elections, according to a data analysis by The Voice that went back to 1990. But, in 2016, National Liberation and National Restoration joined forces behind the candidacy of Luis Fernando Mendoza, mayor of Cañas, and pastor Pablo Guevara, deputy mayor. This may have been an interlude to the success that came two years later for evangelical party National Restoration.

The phenomenon erupted across Costa Rica and the rest of the story is well known. A video went viral of Fabricio Alvarado and catapulted him to the top of the political polls at the end of 2017 and beginning of 2018. In the video, he proclaimed, with passion, that he would remove Costa Rica from the Inter-American Human Rights Court, which had recently issued a ruling requiring Costa Rica to join other countries in Latin America in approving same-sex marriage and name changes on ID cards for transgenders, among other things.

But several academics have explained that this triumph wasn’t so sudden. A map by the Latin American Socio-Religious Studies Program (Prolades) shows that, from 1983 to 2017, Protestantism in Costa Rica moved from winning over 8% of the population to 25% in 2017. While they were few, evangelical lawmakers have also participated in Congress since 1998 and began achieving positive changes for their churches.

Just after the first round of voting a, a study elaborated by the Center for Political Studies Research (CIEP) at the University of Costa Rica and the State of the Nation Program showed that 70% of those who voted for Restoration in the country identified as evangelicals and 20% were catholic.

The studies also show that many of the cantons that most supported Fabricio Alvarado in the first round coincides with the lowest social development index(IDS). In Guanacaste, an analysis by this newspaper shows how La Cruz and Cañas, which have the lowest IDS, voted mostly for the Restoration candidate.

“Evangelical communities have satisfied a social need, in addition to their religious beliefs,” says Prolades president Cliffton Holland, who has been studying religion in Latin America for more than 40 years. He is referring to the fact that it’s a more horizontal religion with fewer hierarchies that people can turn to for help solving their spiritual, economic, sociological and even work needs.

Contrary to Catholicism, Holland says, “poor people are looking for new options and evangelicals represent a more equal society where anyone can become a leader if they have natural talent.”

The Spiritual War

The influence of evangelicalism in politics isn’t new. National University sociologist Laura Fuentes explains in one of her articles that the religion has broad experience in permeating public policy decisions through their bountiful agenda.

For example, she cites the delay in approving in-vitro fertilization, bills impeding abortion and even the episode in 2005 when National Restoration congressman Carlos Avendaño chained himself to the National Monument after the Health Ministry closed 37 evangelical “garage churches.”

In fact, the intention of Evangelical Alliance president Rigoberto Vega is to continue communicating his message to politicians to influence public policy, but stay away from the limelight and controversy of elections.

Fuentes and other scholars and theologians explain that the politicization of religion in a partisan way goes hand in hand with a movement called new-Pentecostalism, which, among other things, promotes a “spiritual war” to defeat “demons” in positions of power in order to “conquer all nations for Christ.”

Among their beliefs are “healing masses,” prosperity theology and other practices like speaking in tongues.

If it sounds familiar, that’s because Laura Moscoa, the wife of former presidential candidate Fabricio Alvarado, and his pastor Ronny Chaves profess this faith. According to researchers, neo- Pentecostals were born of the middle and upper classes in the United States, began a relationship with the U.A. Republican party and financed several presidential campaigns, including that of President Donald Trump.

Guanacaste has a strong presence of evangelical mega-churches called Oasis de Esperanza, which are classical neo-Pentecostal. But UNA theologian and sociologist Alberto Rojas explains that mixing other tendencies or following certain lines of thought depends on the leader of each headquarters

Oasis de Esperanza Church in Cañas. Photo: Angélica Castro.

Rojas said that, whether they are neo- Pentecostals, Pentecostals or from other branches, evangelical voters often identify with candidates who insist on speaking of “Christian values” like many of those interviewed for this story.

Does that mean we will have more pastors or religious fanatics in Guanacaste politics? Not necessarily. Political scientist Felipe Alpízar, who was the director of CIEP, explains that the division of National Restoration and the most recent scandals with respect to how they managed funds could cost them in the next election.

In a panorama where the Evangelical Alliance calls on its leaders to distance themselves from election politics, these cracks could mean fewer voters, says Rojas, the theologian.

***

This story is part of the Transnationals of Faith (Transnacionales de la fe in Spanish) project, a collaboration between 16 Latin American news outlets under the investigative leadership of the Columbia Journalism School. The following are the Latin American partners: Agencia Publica (Brasil); El País (Uruguay); CIPER (Chile); El Surtidor (Paraguay); La República (Peru), Armando.info (Venezuela); El Tiempo (Colombia); La The Voice of Guanacaste and Semanario Universidad (Costa Rica); El Faro (El Salvador); Nómada and Plaza Pública (Guatemala); Contracorriente (Honduras); The Puerto Rico Investigation; Mexicans against Corruption (México); and the Center for Latin American Investigative Journalism, CLIP.

Journalists Andrea Rodríguez, Noelia Esquivel, César Arroyo and Emiliana García contributed reporting for this story.

Comments