The National Institute for Womens (Inamu)’ Affairs bought a $530,000 building in Liberia for their regional Chorotega offices, but since buying it in 2013 has spent more than $110,000 in repairs and studies to check the quality of the structure.

The institution budgeted $880,000 for buying a building here and chose the cheapest option ($530,000) which also earned the highest score in their selection process (89 out of 100 points). But the building didn’t comply with bidding requirements, such has having emergency exits, a parking lot, natural ventilation and wheelchair access.

Of the four buildings Inamu was supposed to buy in 2013 across the country (in Chorotega, Huetar Atlantico, Brunca and the Central Pacific) this was the only one that wasn’t voided. The other regions didn’t buy the buildings, but in some of them, Inamu is starting to build themsaid Inamu’s Chorotega regional chief, Mélida Carballo.

I always insisted that this one must be voided too because the building didn’t have the conditions we were looking for,” Carballo said.

In her opinion, the building has the same problems today as it did when they bought it, and other issues that couldn’t be identified by the naked eye, like leaks in the walls.

In total, they have spent $84,000 fixing the place up (adding walls and doors to separate offices, and rearranging the layout) $14,000 in studies and $13,000 in repairs required to meet Health Ministry standards in 2018.

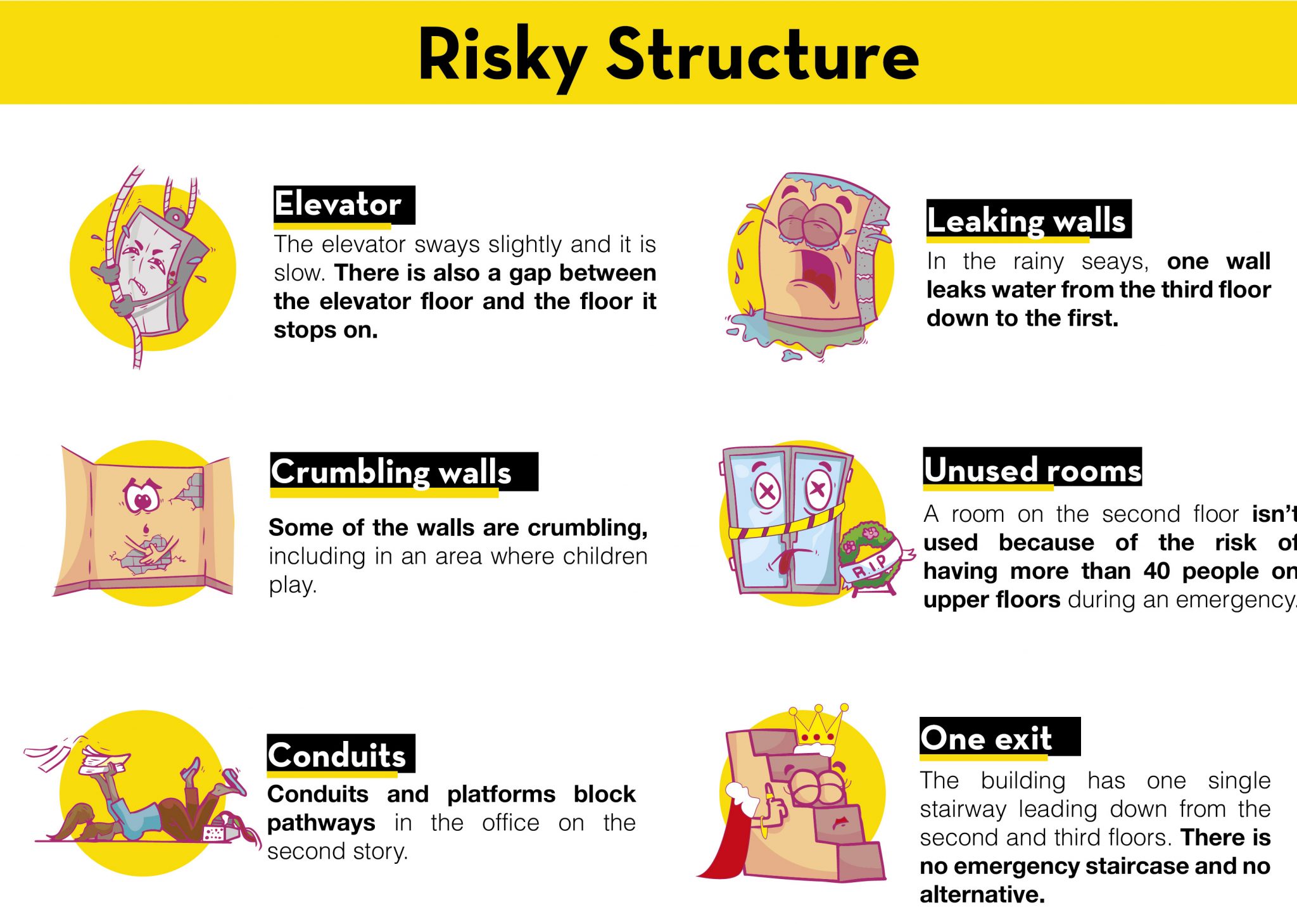

That year, the ministry declared the building was “uninhabitable” because of seven major defects. The institution was aware of some of them before buying it, such as its violations of law 7.600, columns that blocked the only exits from floors two and three and the lack of emergency exit doors.

The three-story Inamu building in the Chorotega region is located in Barrio Moracia, Liberia. Photo: César Arroyo

Inamu presented a remedial plan and fixed the problems, but officials still feel unsafe.

The regional chief gave an interview to The Voice in an office on the first floor where they host visitors in order to not take them to the upper floors. They receive 50 visitors per week at this building and have 19 employees.

We saw certain limitations at the start. It’s a closed space, it lacks natural light, there is no parking lot, the water leaks down the walls, the ceiling is falling in, and there is a wall we call the crying wall…”.

In San José, Inamu’s coordinator of general services Abdenago López says the institutions spent money on ground and seismic studies to “debate the arguments” made by officials in Liberia. López says the building is fine, but added that they hired an engineer who is still analyzing the studies.

“We have a civil engineer that is looking at both studies to put together a report and recommend the next steps to take, whether or not we will have to intervene in the building or what things we will have to improve,” he says.

The seismic vulnerability study, on which The Voice has a copy, says that they must reenforce three columns in order to increase the building’s capacity, which will cost about $67,000 on top of what has already been spent.

“We feel unsafe and there is no precise information. Supposedly there are infrastructure problems, but no one has wanted to provide clarity about the magnitude of the situation,” Carballo said.

But, the head of Inamu’s dispatch in San José, Antonio Trejos, says “the concerns of our colleagues have been taken seriously.”

Uncertainty and Expenses

Inamu also has fixed monthly expenses due to the deficiencies at the building, such as renting a garage for $270 a month where they can park the three cars they have. Three times per week they use community centers to train groups of women who live in vulnerable social situations. According to Carballo, they spend around $35 every time they rent a space for training.

The second floor of the building has a space they considered using for workshops, but the regional chief decided not to use it.

“It implies taking 35 women up the same flight of stairs to a floor that only has one way down, which is the same way they came up. In an emergency, it’s a risk for visitors and employees,” Carballo said, referring to the difficulty and risk that an evacuation would represent, or the possibility the stairway could be blocked or fall during an earthquake. There is no alternative way downstairs.

In total, Inamu pays $3,200 annually on parking and $5,000 on renting rooms at community centers, money they wouldn’t have to spend if the building were in ideal conditions.

Employees don’t use the elevator because of security reasons, because it sways slightly as it ascends and descends and is very slow. It also has a gap between the building floor and the elevator floor. The engineer who installed it, Federico Egea, told this newspaper that the elevator is safe and what makes it slow is the “poor electric voltage” in the building.

That problem, according to Egea, also makes it impossible to go from the second to third floor in the elevator. It must descend first to the first floor to get enough momentum to reach the third floor.

Regarding the gap, he says that a space of two centimeters is allowed, but he made it 2.5 centimeters “so that people don’t get their fingers smashed.”

During the rainy season, concerns increase because the water leaks from the roof down to the first floor along the wall next to the stairs. Some parts of the wall have lost color because of water damage. The institution’s press office said that they are looking into the problem.

Some parts of the walls have lost their color because of the water that seeps. Photo: César Arroyo

Habitual Investments?

Consultant for the University of Costa Rica’s Center for Investigation and Training in Public Administration, Helen Godfrey, says that, in general, institutions look for a guaranteed quality in a building that is taking part in a bidding process and and that they request studies that prove that the structure is up to code with seismic laws.

It’s normal for those studies to be requested during bidding,” says Godfrey.

Inamu contracting coordinator, Carlos Barquero, was one of the three members of the committee that evaluated the purchase and has a different opinion. He says it’s not the responsibility of the institution to verify the state of the building because there is usually a vote of confidence for the procedures done while it was under construction.

“When you buy a building, you assume that everything was verified by engineers’ professional association, city hall and by all the entities that regulate building,” he says. “The plans complied with the requirements and it was a building appropriate for offices.”

Comments