“I told them: don’t pay attention, not all of the fans are like that! Fight, they’re not going to come down!” wrote a woman who follows Municipal Pérez Zeledón in a post on Facebook.

That phrase was shouted from the stands on Saturday, February 4, while the Guanacaste Sports Association (ADG for the Spanish acronym) played against Pérez in their stadium, in San Isidro del General. The fan tried to counteract the insults towards the ADG from other fans of her team.

“‘Nicas, go to second!’ They started to make noises like howler monkeys and started to call us “Nicas regalados” (Nicaraguans given away) and all kinds of xenophobic and discriminatory expressions,” recalled ADG press officer César Blanco. After the game, the team filed a complaint with the Union of First Division Soccer Clubs (UNAFUT for the Spanish acronym).

The comment from the fan of “the warriors of the south” is in response to the official statement that the team shared in which they “repudiate the acts of discrimination that occurred” and ask their fans to prevent this type of situation from happening again.

UNAFUT sanctioned Municipal with a fine of ¢500,000 (about $900 USD). If the fans repeat the offenses in the stadium, the team will have to play the next game without an audience.

“Our complaint is to set a precedent that these situations can’t continue in the year 2023. There can’t be racism, nor xenophobia nor homophobia,” emphasized Blanco. He also clarified that they’ve heard these comments in other stadiums also.

These insults are not new. They don’t occur in a specific stadium and they aren’t only directed toward the players.

ADG supporter Silvia Guevara explained that fans have suffered from these kinds of attacks for a long time.

“As a proud Nicoyan, I don’t feel anything. The truth is that it doesn’t affect me to be called Nicas or paisas, because it’s not an insult. But they do do it as if they wanted to make you feel bad, or perhaps as if to denigrate you,” she explained.

What does the insult “Nica regalado” hide? The Voice of Guanacaste consulted Carlos Sandoval, a researcher at the University of Costa Rica (UCR) who specializes in immigration issues.

An Old Insult that Doesn’t Go Away

“Behind this insult, there is a story that has been going around for a long time,” explained Sandoval. It’s the idea that Costa Rica is the Central Valley and therefore, what isn’t there isn’t Costa Rica. The background to that expression is an idea of where the nation of Costa Rica begins and ends.

“In addition to the territorial factor, there’s the historical one, which is the Annexation of the Party of Nicoya,” added the researcher. Since Nicoya decided to annex to Costa Rica, then the logic exists that Nicaragua “let them go.” From there comes the term “Nicas regalados” (Nicaraguans given away).

The root of the insult is that Guanacaste was not part of the Costa Rican social identity. “Although, ironically, a good part of what is supposed to be Costa Rican folklore comes from Guanacaste,” he emphasized.

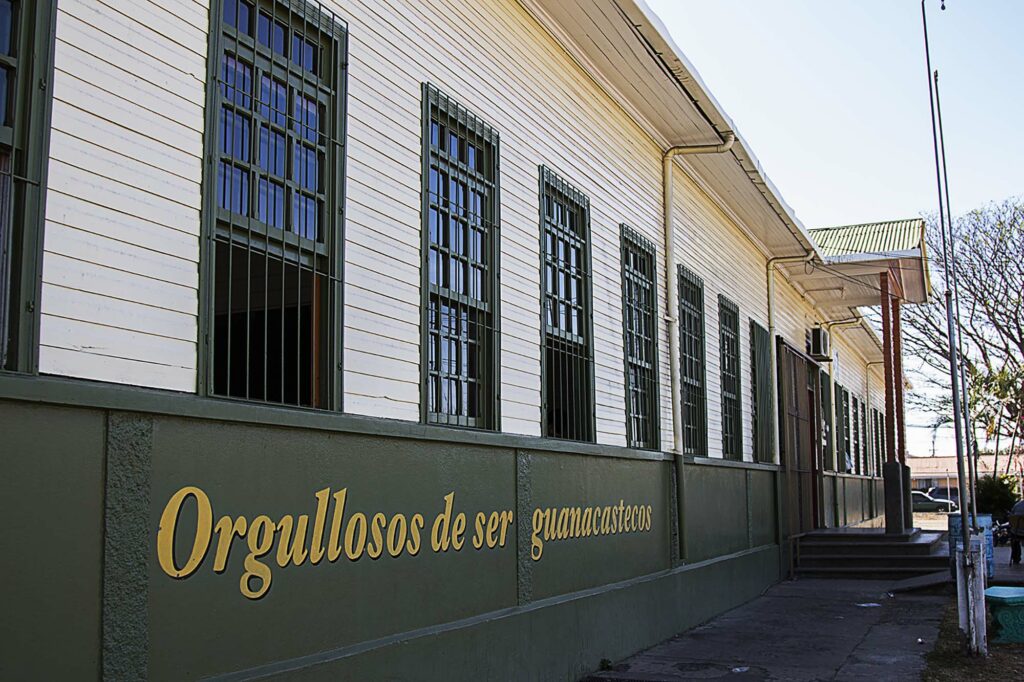

That’s why Sandoval believes that the phrase “Orgullosamente guanacastecos” (Proudly Guanacastecans) that is painted on all the public schools of the province is loaded with resistance, that there is a pride that prioritizes what the communities have in common to question the exclusive rhetoric.

Luis Leipold School in the canton of Cañas.Photo: Ariana Crespo

“Also the idea of ‘de la patria por nuestra voluntad’ (from the country by our will). That is to say, it wasn’t that they gave us away; it’s that we decided to annex ourselves. It’s not a free or fortuitous thing,” he added.

The Mirror We Don’t Want to See

In his book Otros amenazantes: Los nicaragüenses y la formación de identidades nacionales en Costa Rica (Other threats: Nicaraguans and the Formation of National Identities in Costa Rica) Sandoval explains how the idea spread through the 19th and 20th centuries that Costa Rica is a peaceful, democratic country of social equality. But intellectuals and politicians also planted the idea that we have other “ethnic attributes.” For example: that we are the “whitest” population in Central America and that we speak the “best” Spanish in the region.

“Simultaneously, Nicaraguans were becoming ‘the other one’ in the Costa Rican imagination,” wrote the researcher.

To Sandoval, the fact that these insults are said in this 21st century portrays a society that hasn’t finished recognizing itself in its multiculturalism and its regional diversities.

Although one of the first articles of the Political Constitution says that we are multi-ethnic, the researcher thinks that this is only on paper because we refuse to go down the road to make a change in the collective imagination.

It’s a society that is afraid of seeing itself in the mirror of the differences that inhabit it,” he added.

But according to Silvia, the ADG fan, that’s not the only insult they’ve received.

“They call them Chibolo or they call them Juan Vainas (characters from a TV show) when they see them wearing the hat that is a symbol of here in Guanacaste,” she said.

Sandoval explained that this is another form of discrimination, but this occurs between the rural areas and the Central Valley.

“We have a kind of dichotomy. On the one hand, we say that we’re the children of simple laborers, of peasant farmers. And on the other hand, we’re ashamed of those peasants,” said the expert, who explained that this idea has also been built up for decades.

Sandoval commented that one of the works that supports this vision is the book Las Concherías, written in 1909 by Costa Rican poet Aquileo Echeverría. His poems portray the life, customs and beliefs of Costa Rican peasants.

From the book came the notion that the “polo” is someone who doesn’t know the urban codes, who doesn’t know how to dress or speak, Sandoval believes. In short, to be a ‘polo’ is to be a peasant.

The peasant world outside the Central Valley is a kind of “internal other.” The “external other” par excellence are Nicaraguans and here in Guanacaste, these two other identities different from that of the central plateau come together.

“The weight that a story can have in the social imagination is impressive. Because you could say that between Juan Vainas and Las Concherías, there is a common thread,” he emphasized.

A Phrase that’s Out of Bounds

Soccer and identity are two topics Sandoval has written about, which is why he considers it very relevant that these insults are made in a stadium.

“Because soccer is precisely one of the group spaces where identities are validated, both internally and when playing against teams from other countries,” he explained.

The researcher thinks that soccer is a very important didactic tool to broaden this diversity in the national identity, since it is a spectator sport that doesn’t speak to specialists, historians, or the people most concerned about the subject.

There you speak to the hard core of Costa Rica that is afraid of recognizing itself in its diversities,” he added.

Xenophobic and racist comments occur even in the best leagues. In 2021, the English Premier League presented a plan called “No Room for Racism” with the intention of promoting inclusion, equality and diversity.

According to the press officer, César Blanco, this was one of the moments in which the Municipal Pérez Zeledón fans insulted ADG.Photo: Courtesy: ADG

Sandoval believes that national soccer should take stronger measures to eradicate these phrases from sporting events, since it is a way of building social exclusion in the country.

“Soccer is vital to change the culture. This isn’t going to change from the university. You take three points from Pérez Zeledón and put the issue up for discussion. That makes us think about the country in a more creative, less academic and less stiff way,” he added.

The Challenge of a New Story

One way to start changing this, according to the researcher, is to organize an act in which the teams send a message against xenophobia, when Pérez plays as visitors to the Chorotega stadium.

The biggest challenge, and the one that will take the most time, is to build a national identity that includes all differences, Sandoval stated.

“We have a narrative that is not related to the society we live in. The imaginary society and the one of flesh and blood don’t look alike today,” he explained.

Comments