Summer in Nosara is silently ending. It is below 35 degrees with a gentle breeze that indicates good weather. The birds sing like never before and there are iguanas and white-nosed coatis in the streets. Today is Tuesday, but it could very well be Friday. The days pass alone because, since March, the community has been detained in time.

There is little left of the Nosara that we know, where families came to Pelada to watch the sunset or where the bars of Guiones led the parties. Today there is only silence interrupted by the sounds of the jungle and the nostalgia that travels through the air.

In Portuguese, there is a term, Saudade, which means missing something that is no longer there. It is like seeing the empty sea crashing into the sand that saw laughter, dances, and great stories, but that today only has crabs that, in the absence of humans, reconquered the shore.

Animals, which always remain in the jungle, feel that humans are gone. The absence of escapes tube sounds and human voices gives them the confidence to seize the cement. “They go out to explore because they feel the absence of humans and they stop fearing,” explains regent biologist of the Ostional Integral Development Association, Hellen Lobo.

The closure of beaches and borders due to the COVID-19 crisis completely changed a town that depends almost entirely on foreign tourism. Being stopped in time not only brings nostalgia but great economic losses turned into unemployment and uncertainty.

“It’s like living in the nineties,” says Lucy Ramírez, a foreigner who has lived in the town for more than 20 years.

Ramirez is 45 years old and has tanned skin and copper-colored hair, characteristics of spending a lot of time on the coast. She wears sunglasses and well-made makeup, combining a constant smile.

Before the pandemic, she worked full-time as a bartender at the Beach Dog Cafe, a few steps away from Playa Guiones. Now, the owner reduced his hours significantly. In the absence of clients, one week they can open and the other they cannot.

Lucy has worked in the Nosara tourism industry since she was in her twenties. “Nosara’s never been this empty,” she says.

She says that when they told her they were going to close temporarily; she was in shock.

At the time, I was not expecting the impact that the coronavirus could have on us, neither emotionally nor economically,” she recalls.

She always speaks in the plural, because she is a single mother of an 11-year-old girl, who depends on her salary. Right now, and given their financial situation, they are both part of the 1,400 people to whom the Food Bank has donated packages.

Ashamed, she says, this is the first time this happened because before the crisis, “she had never depended on anyone.”

Still, she looks at the bright sight of the situation. She says that since the tourists stopped visiting, she has seen monkeys, white-nosed coatis, and iguanas taking over the streets again. She also believes that people have been solidarity in a way like never before.

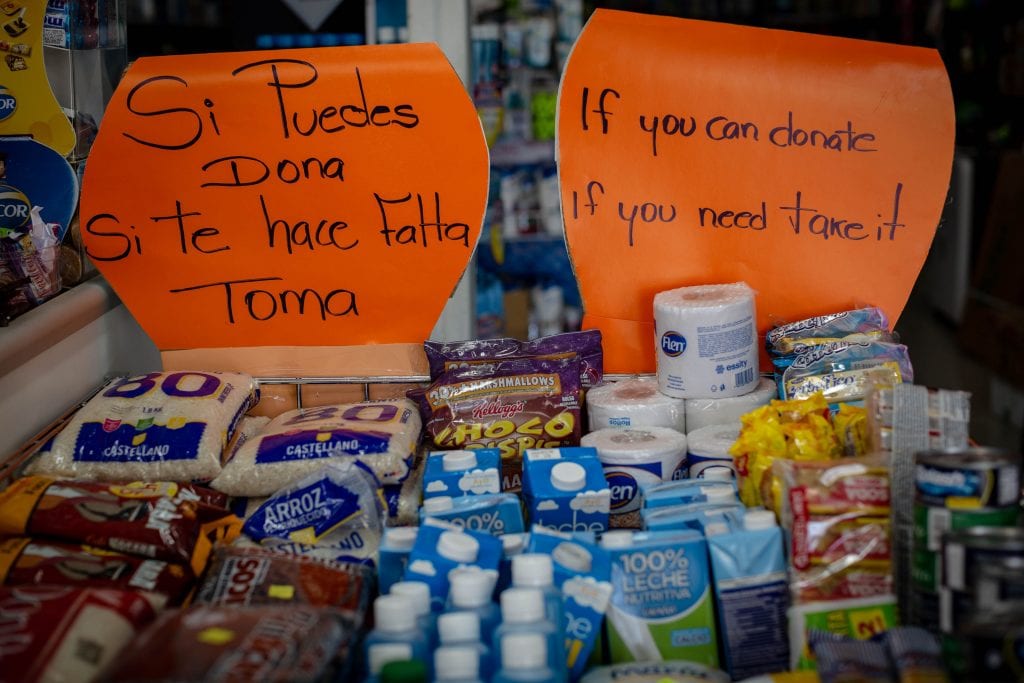

At the entrance to the La Paloma Supermarket, for example, there is a “take what you need and leave what you can” table for those who became unemployed. “This brings out the best in everyone,” says the local.

La Paloma supermarket enabled a table with food and cleaning supplies to people to grab if they need it

Although there are still no cases of COVID-19 in the region, the streets of Nosara are empty. Some locals went out to collect the food granted by the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) but beyond that silence rules.

“Without people there is no money. Without money, there are no people.”

Vanessa Moreno is waiting for the food package that the Ministry of Public Education (MEP) gives her son. She lines up with more than 20 people who disrespect the distance recommendation given by The Minister of Health, every day until exhaustion, at a press conference. Moreno justifies that if the town is without people, it is because of income and not for health.

In March, MEP announced that it will provide in-kind assistance monthly to at least 850,000 students nationwide, which contains basic grains and non-perishable foods, plus study guides for working from home.

We are not afraid, but there is no money to go out,” he says. “See, there are people here because there is food.”

The town’s economic crisis began in mid-March when the borders closed and the large hotels in Nosara, totally or partially suspended their functions. “Since then, everything began to fall, like dominoes,” says Moreno.

Parents awaiting for the food packages

Chandy Cabalceta, the owner of the Il Basilico pizzeria, confirms this. Although he continues working, he reduced the contract of several of his collaborators due to a lack of income.

Cabalceta is 45 years old and insists that Nosara is almost paralyzed in time. As if they returned to the nineties and there were only a dozen bars and restaurants, II Basilico among them. His restaurant is known for concert Saturdays and the exclusive flavor of their pizzas.

Il Basilico is no longer what it was, not right now. Although the restaurant maintains its face to face modality under the corresponding measures dictated by the Ministry of Health, nobody arrives. The highest current income is from the express service. Otherwise, Cabalceta says, the business would be unsustainable.

The restaurant went from generating around $2 thousand in one night to around $6 hundred on a very good day, although the owner claims the profits could be worse. The problem relays on the debts he keeps paying because they are not included in the state’s financial exceptions.

Although he reduced the hours of all his workers, he tries not to fire any because most of them have been working with him for years.

We have children and needs. Here we are going to continue working,” he says.

There is a feeling of nostalgia when seeing an empty restaurant. “No one here missed a concert Saturday,” recalls the chef.

After the storm

Cabalceta says that if everything improves by July of this year, the damage to the business will not be serious and the music will sound again. However, Health Minister, Daniel Salas, has been emphatic during the press conferences that opening borders or beaches, at this time, is not a possibility.

Although we are facing a global pandemic where everything changes rapidly, life in Nosara continues to pass slowly. Rich Burnam, CEO of the real estate firm Surfing Nosara, justifies this by saying that the majority of the locals live in peace because they hope everything will resume its normality soon.

Burnam, a US citizen, has lived in Nosara for almost 15 years and claims, he raised his family in this place and feels part of the local community. Although it is rare for him to see the people in a silence never seen before, he says he is grateful to experience the pandemic in this place.

The Nosara streets remain almost empty of vehicles since the covid-19 outbreak

“I think we are all happy to have faced the virus in a city like this,” a community where people can go out to their yards and continue living nature from home.

That, plus the measures that the central government has taken in the face of the crisis, means that real estate prices in Nosara are maintained, and interest in them has even increased.

Burnam says that although it has lost some businesses, Surfing Nosara is receiving calls from foreigners interested in investing or living in the community after the pandemic.

If before Nosara was already seen as a paradise, that vision of security that the government gave increased it more,” he says.

All of these plans may fall apart depending on whether Costa Rica opens the borders in about three months. If not, you will have to redesign the company’s budget, reducing operating and payroll expenses.

The Nosara Civic Association (NCA) depends on this as well. The crisis began in March, the month in which all its members must pay their annuities with the organization. Two months later, most have not deposited, says the association’s project coordinator, Francisco Jiménez.

The NCA, says Jiménez, depends entirely on the donations of its members, and if they stop coming completely “it would be a disaster.” The organization is in charge of recycling projects within the already closed Nosara garbage dump and recently supported the call center department of the Food Center. For now, they will rely on voluntary donations and will participate in different scholarships and international projects.

***

Nosara is a community with a thousand faces, and there is no universal concept that can summarize it. Daniel Salas insists on saying that this will not end soon, but the nosareños speak from the nostalgia of what was taken from them and the hope of what they will be again.

Both Lucy Ramírez and Rich Burman say that after the COVID-19 ends, the first thing they will do is go to the beach. But for now, time will continue to stand still for a few weeks or even months.

Comments