Avana parks her sandals in the entrance of the juice bar and walks toward a table while he holds a cup of thick, bubbling cacao in his hand. She sits on the ground that She touched for the first time 18 years ago, when she was only 20 years old, and narrates how she left Belgium chasing a childhood love.

In a low voice and with elaborate Spanish, she explains to me that she never imagined that she would end up building, together with other wanderers, this community called Pachamama: a wooded meditation paradise with houses, stores, workshops and communal rooms and kitchens.

In this colony of foreigners, the majority Israelis, they over-pronounce the letter ‘r’ and they hug each other with their eyes closed and a perpetual smile on their faces. In the mountains of Guanacaste, between Ostional and Junquillal, they found a more authentic way of life.

The community has almost 70 residents that work on the construction and upkeep of the place. They give meditation workshops and silence retreats to more than 1,000 visitors per year who come seeking the same spiritual awakening that brought the pioneers here at the beginning of the year 2000.

Before putting down roots in Costa Rica, the first residents traveled around Australia, Japan, Korea, Brazil, India, Israel and many other countries. In each country, after silent meditations, new members joined them until they had enough to form a community.

“It’s a way of life in which the essence is meditation and working on yourself,” says Nikaj, 37, speaking loudly to drown out the noise. We are in the carpenter shop, a building in Pachamama where he works from Monday through Saturday.

“I found a positive goal waking up every morning, not to fill my pockets but to help a place and its people. For me, at the end of the day, those actions translate into a better world.”

Building Utopia

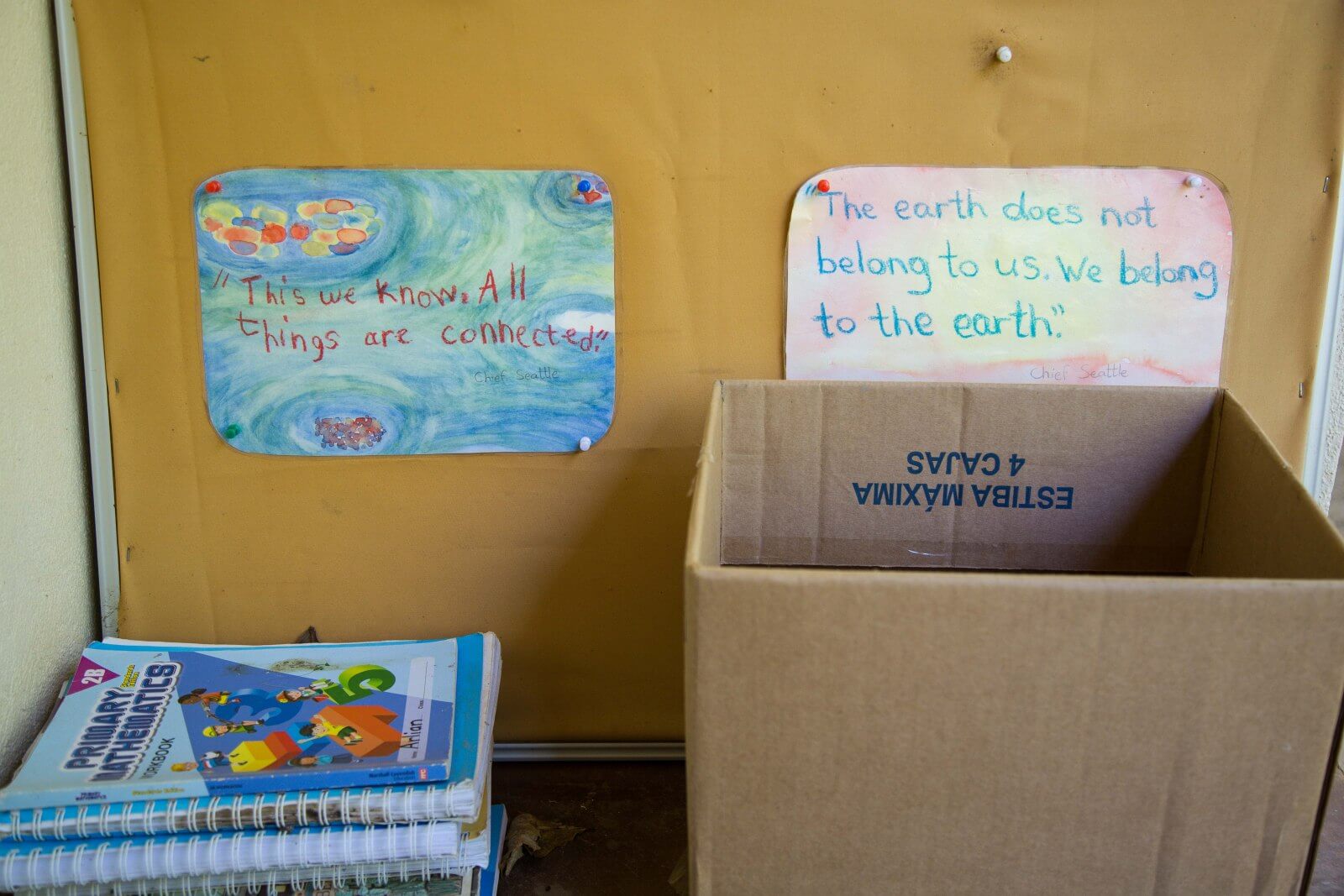

Protecting nature is fundamental for this community. As soon as they set up shop here 18 years ago they started to sow native spices across the 500 acres of land (previously pasture). They wanted to recreate the original habitat and they achieved it: The new forest attracted new birds and mammals. Despite being a 100% international community, the inhabitants of Pachamama don’t isolate themselves.

“It’s really easy to create a bubble and we don’t want to be one,” Avana says while she drinks her cacao, already half gone. “You can’t see Pachamama as separated from the rest of the communities.”

In fact, everyday before 6am, 30 residents of Ostional ride on motorcycles along the rocky road sweetened with molasses that leads to Pachamama. They work in the carpentry shop as long as there isn’t a spawning of turtles, since many of the workers are also part of the Ostional Association of Local Guides.

“When the turtles arrive, we allow workers to come in to work later,” Nikaj says. Work doubles on those days because the number of workers is reduced.

The Revolution in Silence

When the people who live in Pachamama answer questions about why they are here, many of them name the same reason: Tyohar.

Tyohar is the spiritual leader and main founder of Pachamama. He has his own Instagram account with photos of nature and doesn’t look at all like the typical centenarian gurus with white beards. Every week, he leads a meeting called satsangs in which he offers reflections on questions from those in attendance.

While meditation was the spiritual experience that knitted this community together, Pachamama doesn’t have a dogma nor an agenda. They also don’t practice any official religion, so there is no segregation.

Every night at 6:30pm, the community crosses the dark trails of the mountain with lanterns and they become a parade of fireflies. Once in the communal room – named after the Indian guru Osho – they meet to meditate in silence for 45 minutes.

Once night time arrives, the trees and plants swallow up, one by one, the lanterns and houses where visitors sleep, and the sound of the forest dazzles as heavy animals are heard walking all around.

When visitors arrive at Pachamama they are told not to be afraid of the nightly noises and that there are no dangerous animals on this mountain that Tyohar and the pioneers chose.

In this anti-publicity spot, hidden so that only those who really want to come arrive, there is never a lack of skinny people in loose pajamas that populate it. Paradises have never needed much marketing.

Comments