Antonio and Marta started living together thirteen years ago when she was 17 and he was 33. “I left my friends, family, everything because he asked me to,” she says in an anonymous interview with The Voice of Guanacaste.

Three years later, Antonio started beating both her and the only child they had in common at that time.

Antonio ended up in prison for “a drug problem,” two years ago. She continued to make conjugal visits with him, bringing along their two children and treating him to homemade food in spite of his yelling and beating.

“He’d get upset over any little thing. He never said thanks. He always said that everything I do is wrong. I felt like I was drowning, that I didn’t know what to do.”

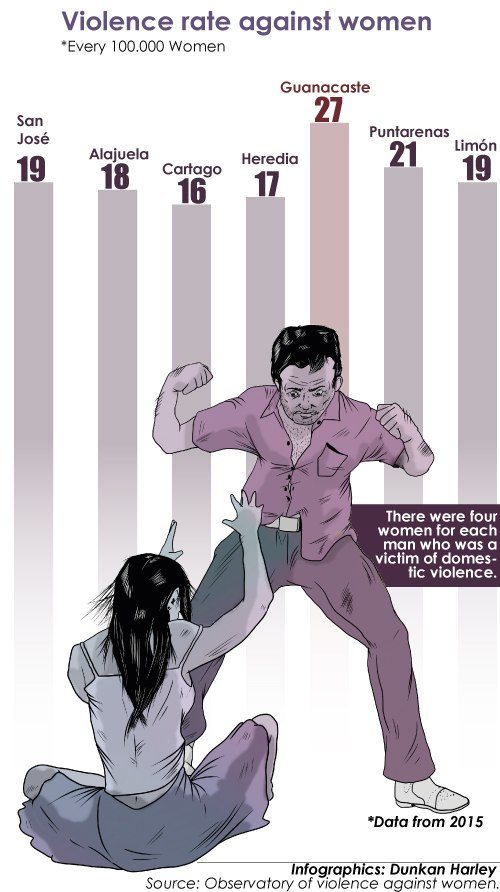

Since them, Marta, originally from Tilarán, hasn’t dared turn in her aggressor. In Guanacaste, the rate of domestic violence against women was more than 38% higher than the entire country’s average for 2015 (27 versus 20 per 100,000 women). And this is without counting the women who do not ask for restraining orders (there is no data for this statistic.)

Guanacastecan women wear the painful crown as the women who suffer from the highest intensity of domestic violence in Costa Rica.

On average, thirteen women went every day to courts every day in 2015 to ask for restraining orders against aggressors that lived under the same roof, and at least four sought protection under the Law of Penalization of Violence Against Women.

The most frequent cases in the courts are violations of restraining orders. This means that even when women speak out against these men, the women are still vulnerable to their aggressors. This renders legal protections moot.

Beatings, threats, and insults are next on the list.

Attempted murder against women, or femicide, adds another thorn to the crown: the rate is higher in Guanacaste’s two circuit courts than anywhere else in the country. Six out of every 100,000 women are affected, when the average across the country is four.

An analysis done by The Voice of Guanacaste using data from the Gender Violence Against Women Observatory of the Judicial Police. The numbers are from 2015, with a few statistics from 2016.

Changing lives

Marta dared file a restraining order against Antonio in October, 2016, after thirteen years of aggression. She felt capable to do it after undergoing psychological treatment in Liberia, at the National Institute of Women (in Spanish, Inamu), where they told her that she was worth more than that, that she could do it by herself.

“I was ready for him to come home after he got out of prison, but with the psychologists’ help I realized that I had to stop this. I told him no and then got a restraining order so he never comes near me.”

The only branch of the Inamu in Guanacaste is headed by Mélida Carballo, in Liberia. It took her sixteen years from when she first opened the office to obtain state funds to form a team to help victims of gender violence.

Today, the office has a female psychologist and a lawyer for the entire region that assist women like Marta, who is now 30, works as a cook in a hotel, and is certain that she wouldn’t have gotten out of her situation if it hadn’t been for those two women in Liberia.

In spite of the high rate of people in situations similar to María’s, the human resources dedicated to the Inamu is low in the region. “Our resources are stretched very, very thin,” said Carballo.

Neither her job nor institutions that are supposed to prevent violence have achieved a reduction of these rates at a macro level: the rate of complaints for domestic violence have remained practically unchanged over the last five years in Guanacaste. However, the help of psychologists and social workers have made a difference in some of the women they are able to assist.

To increase their area of impact, Carballo also also helped to create women’s offices in the municipalities in each of Guanacaste’s cantons. Each office is comprised of a psychologist or a social worker.

In addition to her projects to empower women in the canton, these municipal workers must attend to cases of violence that are referred to other institutions according to their evaluation.

The team at the Inamu also leads four support groups per year, in different cantons, to help “survivors” of domestic violence. After a rigorous selection process, the women who enter the course usually finish it and decide to leave or denounce their partners.

Some of these women get money for bus fares or a meal because they realize that poverty creates difficult conditions, and some women don’t have money for these things. They realize that a bus ticket might be the difference between a beating and a healthy life, between life and death.

Broken intentions

Why don’t women leave violent men? The same reason that they enter into this circle of violence: poverty, inequality, and a lack of opportunities are the breeding ground for domestic violence, according to Monserrat Sagot, doctor of gender sociology.

“When men are not able to construct their masculinity by being providers, having a good job, they turn to other forms of masculinity, like violence,” said Sagot.

Beaten women tend to be vulnerable to gender roles imposed at home, which are usually based on ignorance, said Melida Carballo, from the Inamu.

“They are mothers, they have more than two children, and they live in poverty or extreme poverty. Often the only income comes from their partner. Any chance to make their own money tends to be very informal,” explained Carballo.

These women’s courage to report their partners breaks down when they see their children go hungry, explained the sociologist Rebeca Chaves, who spent three years working at different branches of the Public Ministry’s Office for Victim Assistance in Guanacaste.

“They come and make the report, but then they withdraw it because if he’s in jail he can’t work and that’s how they get by,” said Chaves. The Public Ministry assists everyone who presents a penal claim against their aggressors. When necessary, they will even transport the women from their homes to protect them.

When the women give up, the prosecutor’s office can continue the case, said Chaves. However, they cancel notifications to the victim and remove the restraining order, meaning the aggressor can return home with his family.

Why Guanacaste?

Surviving violence in Guanacaste is not easy: many towns are far from schools, health centers, and police stations, making access difficult not only to justice, but also to support networks of family and friends.

Even the profile of batterers in the province is different from the rest of the country, according to offices that support survivors and victims.

Chaves feels that aggressors in the province oftentimes have Antonio’s profile: men who can turn suddenly violent without an apparent trigger. This unpredictability makes assistance for women making their first report even more urgent.

“In other parts of the country you see a circle of violence that starts with psychological aggression that then escalates. In Guanacaste, this period of escalation is more immediate,” she said.

Another hypothesis is the proximity of the border: “Men feel freer because they can cross the border into Nicaragua and flee from justice in Costa Rica, explained Chaves.

Remoteness also makes access to information difficult for women to know their rights.

“Sometimes the women themselves don’t know that they’re in a violent situation. When they get this information they go file a report,” said Marcela González, a domestic violence judge in Liberia.

Marta realized that she had to denounce Antonio precisely when she started an English course at the National Training Institute and her teacher referred her to the Inamu to get therapy. That day the spikes on her crown began to fall off.

Where can you find help?

If you are being hurt by your partner or other family member, you can always call 911 and ask the police to help you file a report in court. You can also go to:

- The Inamu branch in Liberia’s

- The office for women in each municipality

- Offices of victim assistance (at each circuit court)

- Social workers at public hospitals in the province

Comments