“La mona” (the legendary witch monkey) wasn’t the only character that inhabited Ronald Díaz’s head during the days of his childhood in the early 80s. The protagonists of Mazinger Z, one of his favorite animated series, also coexisted. They leaped from his head onto the dirt roads of San Roque, the neighborhood where he lived in Liberia with his mother and six siblings.

His hands sketched these characters with a stick since he didn’t have pencil and paper. And as soon as he had notebooks for school, instead of filling them with class material, he saturated them with drawings, which earned him more than one scolding for “being lazy.”

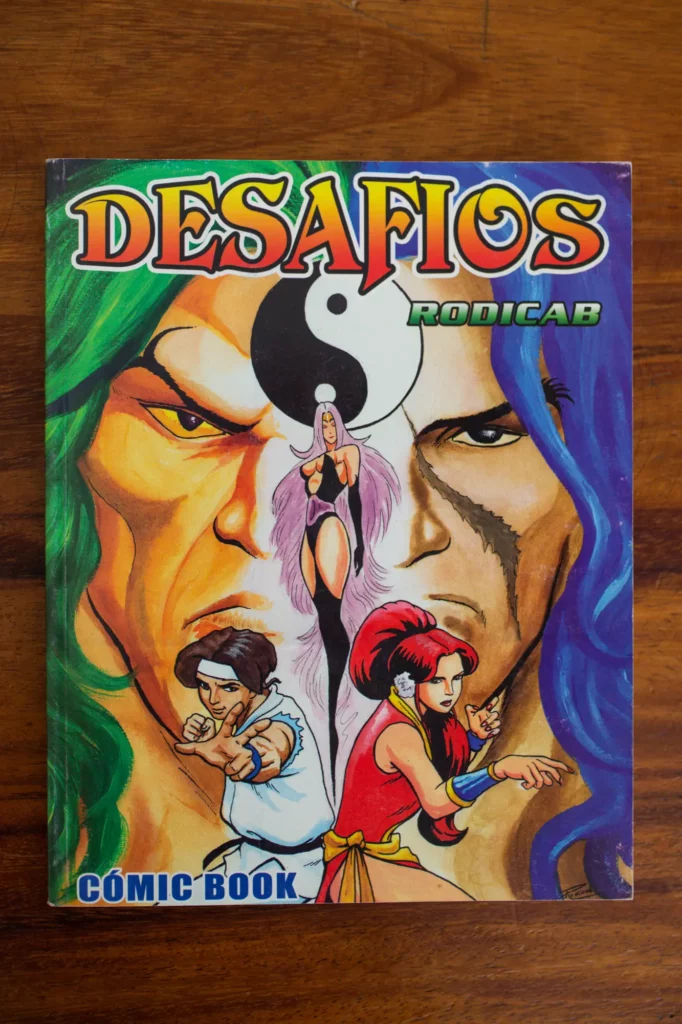

Decades later, without anyone teaching him, Ronald started making comics and became the author of the first graphic novel in Costa Rica, called Desafíos (Challenges). But it would take a while longer for him to find his own voice, and he would accomplish that by combining the two things that he most enjoyed as a child: drawing and his great-grandmother’s stories.

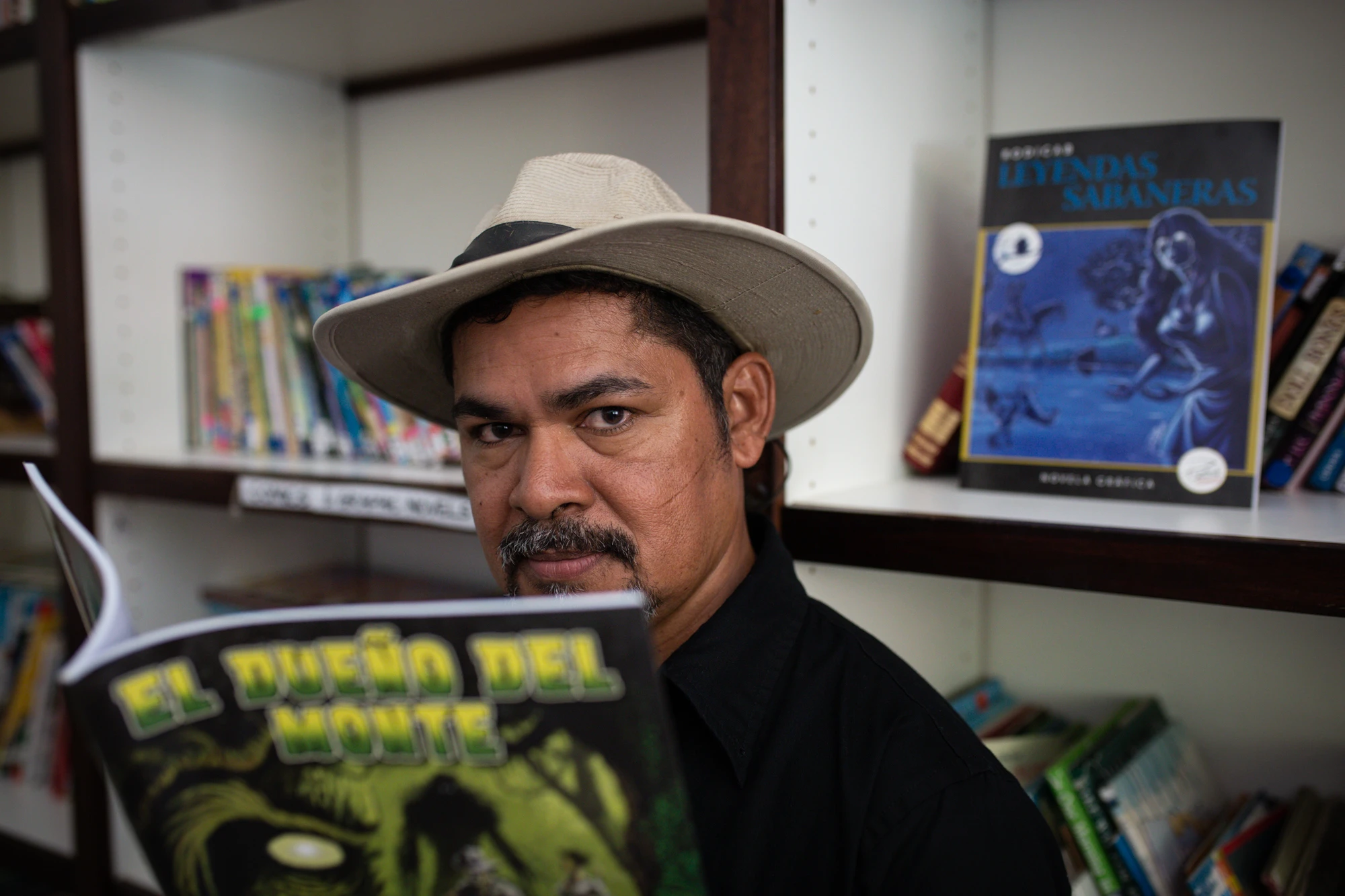

We’re in the library of a school in Potrero, Santa Cruz. Ronald has a spot at the school’s book fair. Ronald is in his element, surrounded by letters and drawings. When he talks, he does so slowly and deliberately and is meticulous about details. So many years of telling stories have taught him to spin tales with the patience of a craftsman.

What does the artwork in Guanacaste’s restaurants look like and what does it say about our identity?

He inherited this love of storytelling from his great-grandmother, which is why he wasn’t content with just drawing; he wanted to do something with those drawings. So he began preparing to learn to tell stories.

Sketching the Path

With the few copies of comic books that arrived from the United States to Liberia, Ronald began to learn about graphic storytelling.

“I made sure that the drawing was of good quality, because really those were my teachers: Frank Miller, Will Eisner, Milo Manara,” enumerates Ronald.

The movie theater and Japanese anime series were also two great schools for him. He saw the effects, the framing, the angles, and imagined how to apply them to his comics.

“In my childhood and adolescence, doing this professionally was a dream. It was a dream that at some point I’d see one of my works in the display case of a bookstore,” he recalls.

That dream started to materialize in 1998, when he debuted in the third and final edition of a San Jose magazine called Camaleón. On that occasion, he published the comic of a character named Rodicab (Ronald Díaz Cabrera), an alias that has endured to date and with which he signs his works.

José Ulloa, editor of Camaleón, describes the magazine as one with stories of humor, fiction, and irreverent adventures that invited different artists to publish their comics, but it only published three editions.

“Most of the projects didn’t materialize, they cost a lot of money, distribution effort and there were quarrels in the groups. We heard the drama of the comics from abroad, we wanted to be like them so much that we began to reproduce the conflicts without it being worth it,” says José.

Other efforts similar to Camaleón appeared later, but Ronald didn’t want to return to that dynamic. He scraped together some savings and began his journey to publish his work on his own.

The Biggest Challenge

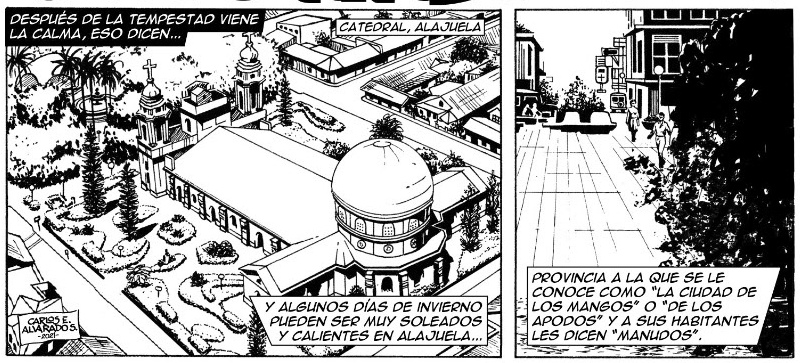

It’s the year 1977. A police sketch artist named Carlos Pincel drives around the streets of Alajuela with his Ferrari. His job is to make forensic portraits and fight crime.

That artist is the character of a comic and its author is a 17-year-old boy who uses the same name as his protagonist for his signature.

Carlos Alvarado, better known as Pincel, was the first person in the country to create an action comic. He published a daily strip in the newspaper Excelsior. Before his, all of the comic strips in the country had been political humor.

Like Carlos, Ronald also broke a paradigm. In 2004, he published Desafíos, a story about self-improvement and martial arts, with graphics very similar to his adolescent models: Dragon Ball and Knights of the Zodiac.

Ronald Díaz exhibits one of the last copies of his first book, Desafíos at book fairs and presentations. The rising popularity of comics and of collecting them has caused many to seek out a copy.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

The issue of Desafíos that Ronald exhibits is impeccable even though it was printed almost 20 years ago. It’s one of the five that he has left and it’s no coincidence that he takes such good care of it because it is a relic.

“As far as I’ve been able to discover to this day, Desafíos is the first graphic novel: a comic told as a novel. At a time when ‘we were far off the mark’ and all the projects were canceled, it puts a mark on what we should do: tell the complete stories,” explains José, who is also an audiovisual producer and is currently producing a documentary about the history of comics in Costa Rica.

In a short time, Ronald learned, and in the worst way, that the most difficult thing wasn’t getting the funds for publishing 1,000 books, but rather the distribution. Social networks didn’t exist yet to sell his book without intermediaries. He depended completely on television or newspapers to promote it.

“So I found myself with a lot of copies without the ability to sell them. [It was] the first graphic novel to be published in Costa Rica, but due to those limitations at that time, it wasn’t renowned,” laments Ronald.

The first and only edition of Desafíos took more than a decade to sell out. Although it’s no longer for sale, Ronald takes advantage of social media accounts dedicated to spreading the word about national comics and geek culture events to let people know about the novel.

People came last year during the International Book Fair just to look for Desafíos, but it’s sold out now. That convinced me that I have to do it again,” he believes.

From His Great-Grandmother’s Voice to His Own Voice

Ronald arranged his three books in chronological order. The one in the middle has a cart with oxen, a monkey and a weeping woman on its cover. It’s a collage of legends tinted by the blue veil of night. At the top, it says “Leyendas Sabaneras” (Legends from the Savannah).

“Before Desafíos, it never occurred to me to start with the legends, which were the stories I grew up with. I didn’t appreciate that with the value that I see now. Our cultural legacy was an everyday thing,” comments Ronald.

He began to collect stories from the province’s oral tradition to transfer them to comics. The first one he did was for the newspaper El Sabanero. His editor suggested that he do a comic strip related to Guanacaste’s culture and he recalled the story of a man from Santa Cruz named Chú García who fought with the devil. They published it and it was very well received by the public. At that moment, Ronald understood that he could use comics to promote the region’s stories.

“When one, as an artist, realizes that he has a responsibility, he’s no longer the same; he no longer thinks only about what he likes, but rather what contribution he is going to provide to the culture,” he explains.

José thinks that Ronald is a very good role model for the use of comics to educate and document.

“It’s not only that he tells the legend, but rather how he is telling it, you see a whole way of life: what a canteen is like, how a horse is saddled, the style of clothing. So every detail, every single vignette is an education regardless of the story it tells,” he explains.

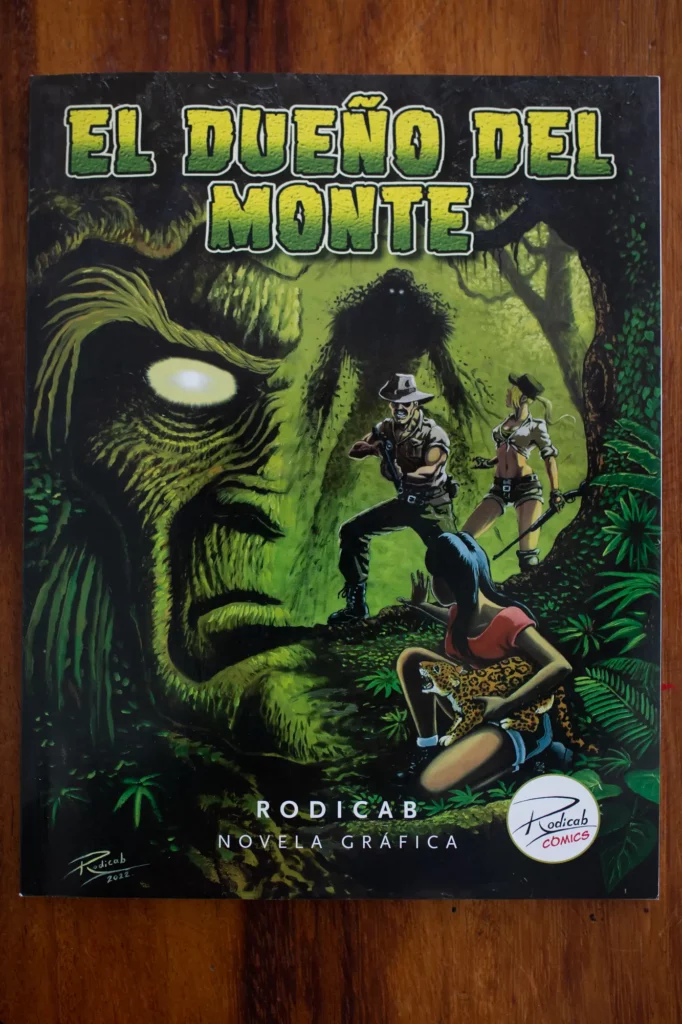

The last book on the table is El Dueño del Monte (The Owner of the Forest), the legend of the spirit that protects the forest from hunters. Unlike Leyendas Sabaneras, this book doesn’t stick to the version of our grandparents, but rather uses it as a starting point to create an original story.

“I place the story in modern-day Guanacaste, with the problem of poaching and the illegal trafficking of species, where this respect for the spirits of the forest no longer exists, so what the Owner of the Forest did to protect it no longer works,” Ronald explains.

The strategy used by the spirit of the forest is to ally with an indigenous child to materialize. According to the author, his intention with these characters is for indigenous and rural people to feel represented. In addition to environmental conservation, the book deals with issues such as bullying, discrimination and political corruption.

El Dueño del Monte (The Owner of the Forest), his latest graphic novel, touches on issues such as corruption and wildlife trafficking. Ronald Díaz explains that as an artist, he feels the need to contribute to culture and also to environmental conservation.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

José believes that one of the reasons why we continue to keep these expressions of oral tradition, like the Owner of the Forest, alive is because people have made them their own.

“Not only is there a purist part that has maintained them, but fiction has been renewing them in some way, adding to and updating them. I think it’s worth doing both: the educational value that the original story has is important, just as it’s very valid to say ‘how can we make this story grow?’”, he expressed his opinion.

More Hands Drawing

Indigenous people, monsters of the forest, Lloronas (legendary weeping woman looking for her children, whom she drowned) and Ceguas (legendary beautiful woman who tricks womanizers and then changes into a woman with a horse skull for a face) with very fine dresses. Characters like these embody Ronald’s stories. For him, the design of these archetypes is very important.

“Sometimes we’re criticized a lot for that, but there are little things there that I at least try to respect to attract attention. I started trying to draw well. All the characters that I was inspired by maintained that aesthetic,” Ronald affirms.

The criticisms that Ronald mentions have to do with the sexualization of female bodies in comics.

The editor of the Costa Rican geek magazine The Couch, María José Madriz, explains that this phenomenon is not unique to comics; it also occurs in other types of formats such as series, movies, video games and anime.

“The geek culture from its inception has a super masculine focus. So women have not been represented for years. Before, there were no female heroes; they were always the romantic interest [of another character],” he explains.

When female heroes began to appear, they did so as a trading card, explains María José.

“So that’s where this sexualization tool to get sales begins and it’s one thing for the other. ‘Ok, man, your character is very cool, super well written, but lower her neckline so that she sells,’” he adds.

María José believes that sexualization has historically been a hook to attract attention, but over the years, what has sustained readers are the stories and the depth of these protagonists.

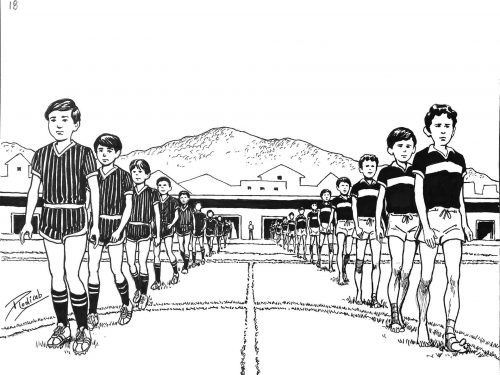

Excerpt from the Carlos Pincel comic

The second big change that María José points out is that more female writers and cartoonists have begun to create their own content. This gender inclusion was also accompanied by a diversity in nationalities, age and sexual orientations that added to the complexity of the characters.

Gender awareness and feminism have also permeated the narratives of comics and other works of fiction, which is why María José doesn’t venture to judge a story from the outset when he observes these representations of female bodies.

“I’m not going to always assume that it comes from a bad intention. I need to see the story and see what role these women play, and from there, make decisions based on my criteria as well. I think there’s a difference between a sexualized character and a character with sexual power. It might be the same drawing in the end, but the background and the form are noticeable,” he explains.

María José, Ronald and José agree that we’re experiencing a boom in the production of comics in the country and that this format is a good mechanism for transmitting stories from oral memory, but also for creating original stories with complete freedom and independence.

It seems to me that the most interesting thing is how you can make a product that feels global from your personal experience,” María José remarked.

Comments