Violence against women is fed, like an insatiable pack of wolves, by its different expressions: patrimonial, psychological, cyber, physical, sexual assault… If nobody stops it, it evolves until it reaches its irreversible form: femicide.

Rosario Gutierrez, or Chayo as she likes to be called, remembers very well when Adrian Salmeron Silva attacked a family of five people in Matapalo of Santa Cruz. The episode left the community and the entire country in shock and was a breaking point for many institutions and groups from different communities to fight so that the nightmare did not happen again.

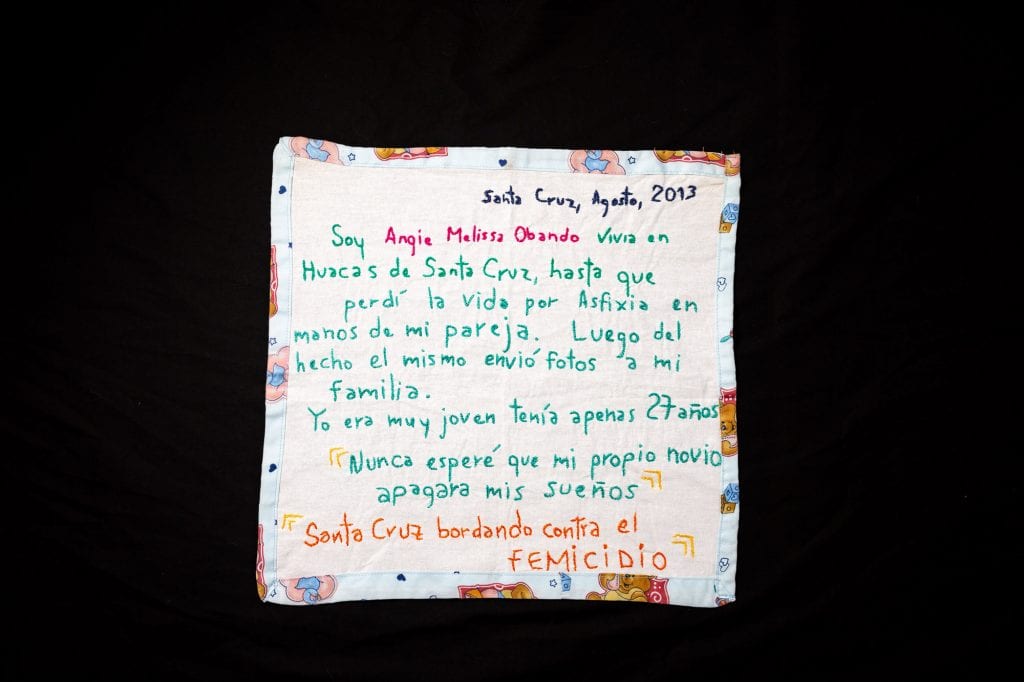

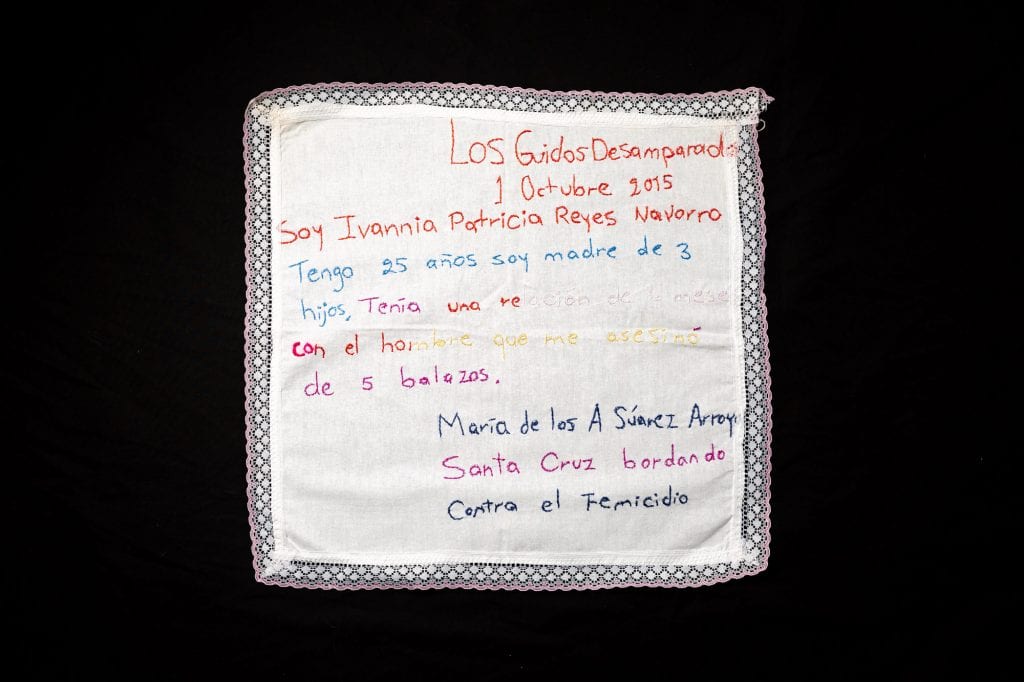

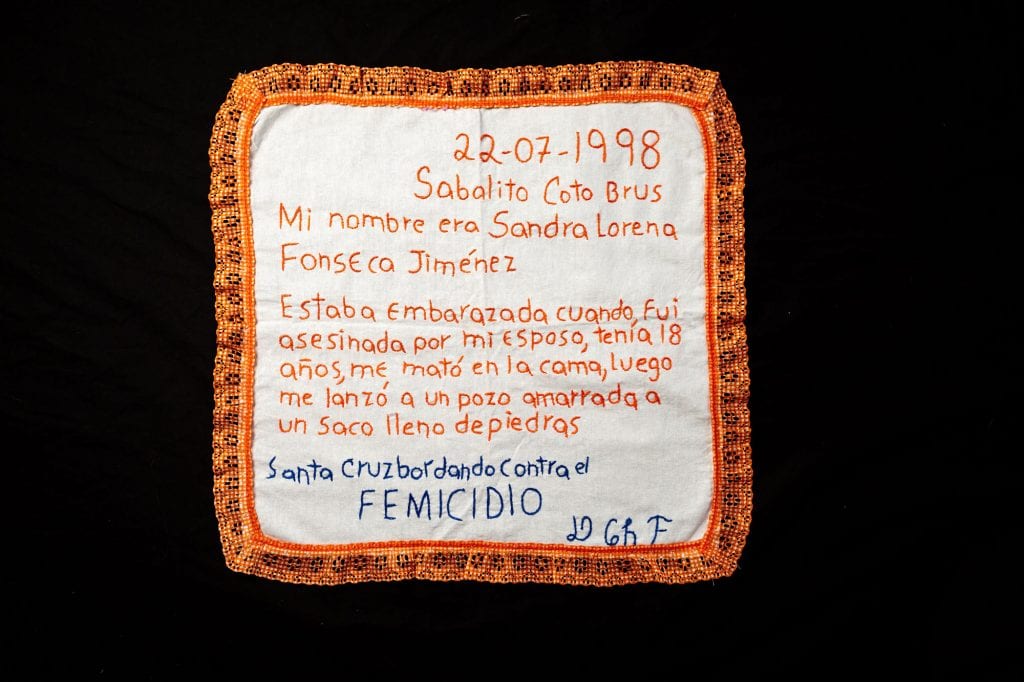

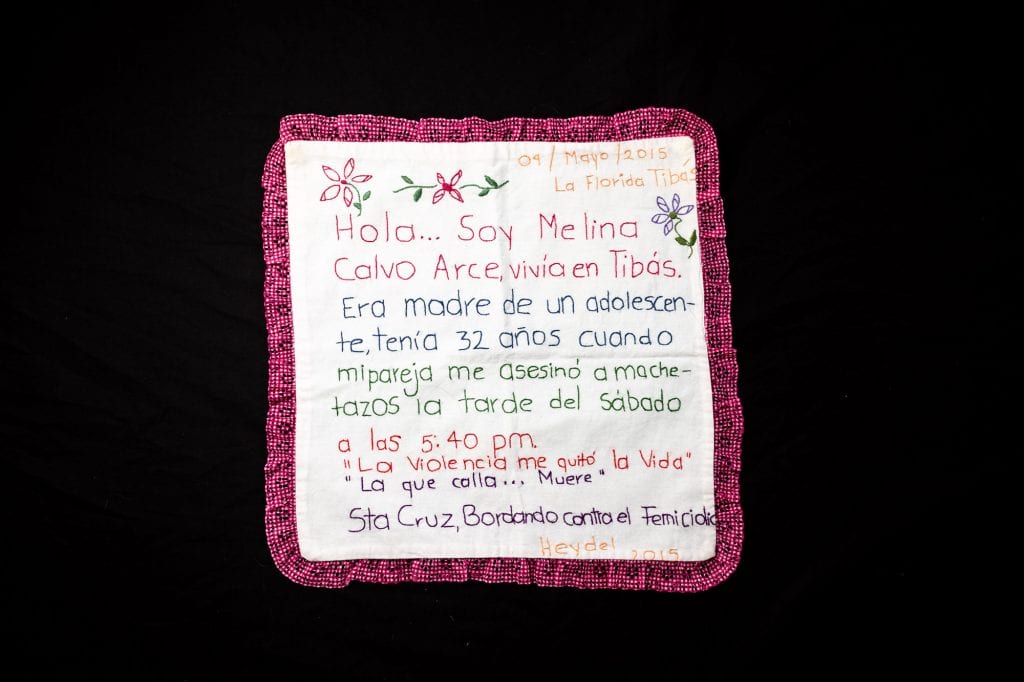

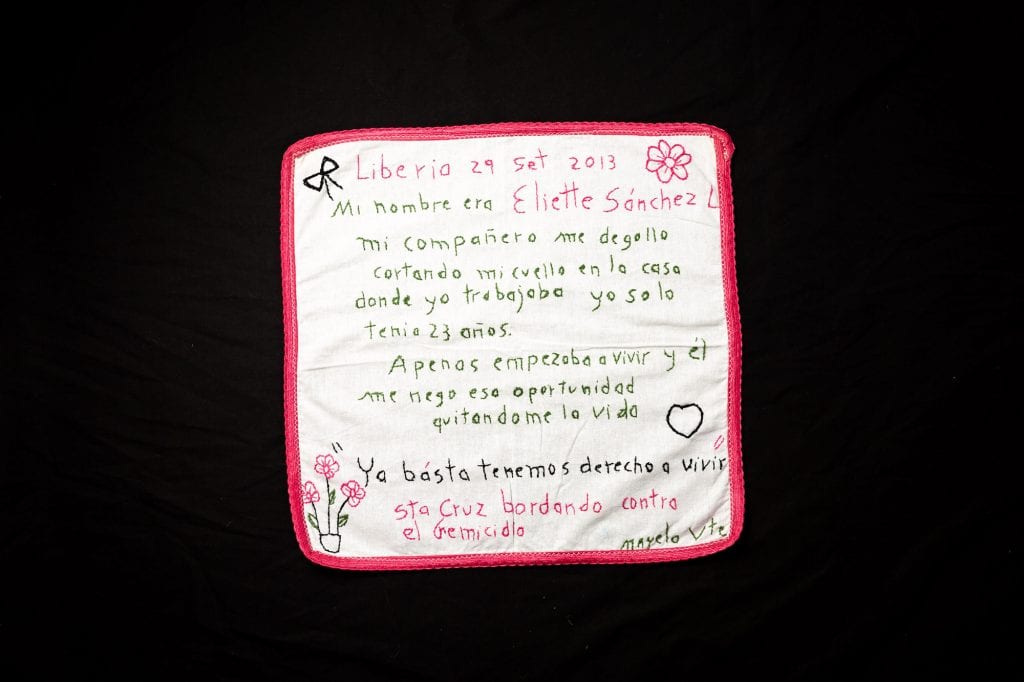

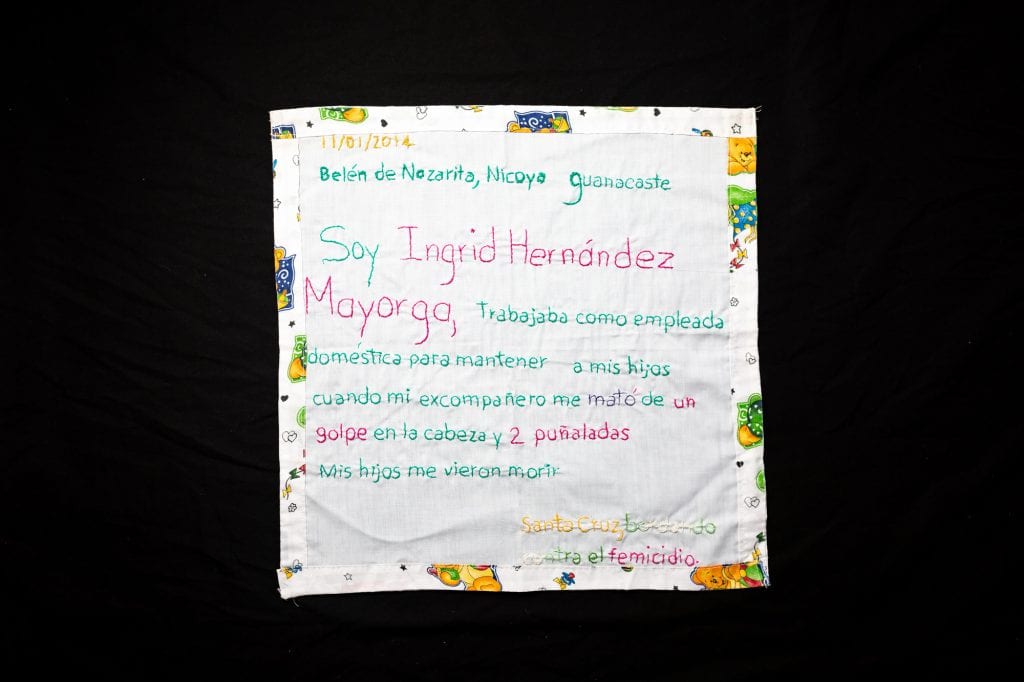

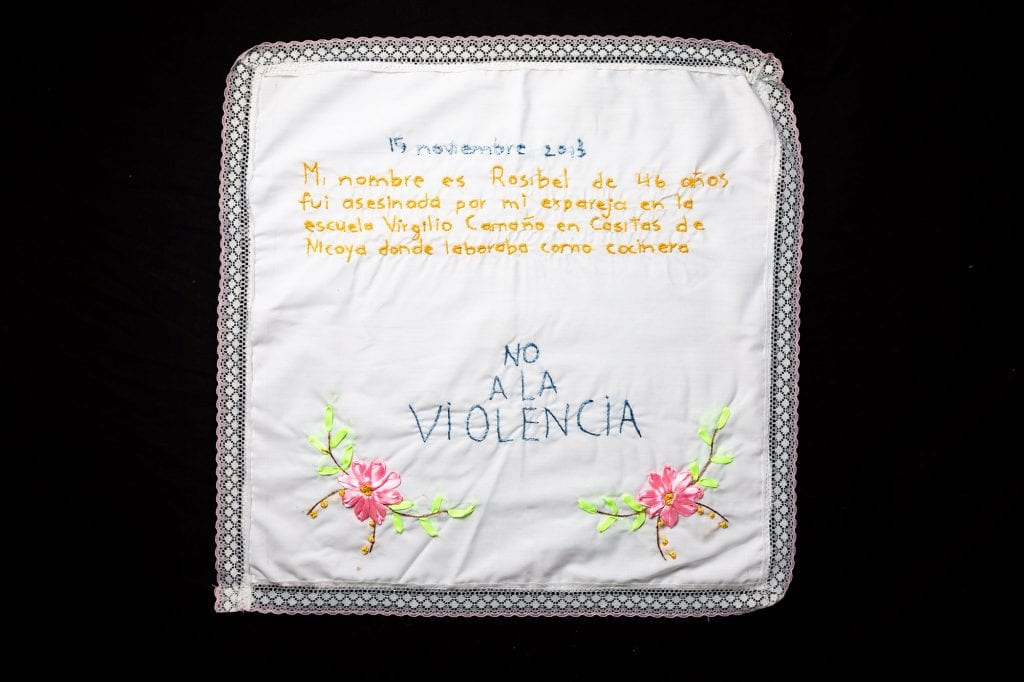

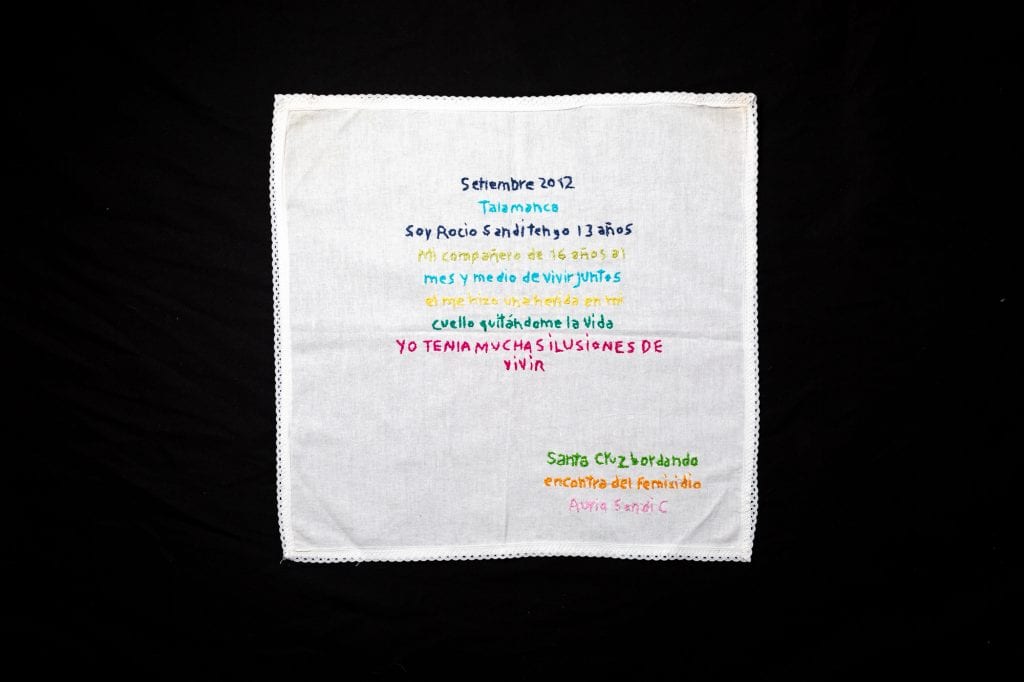

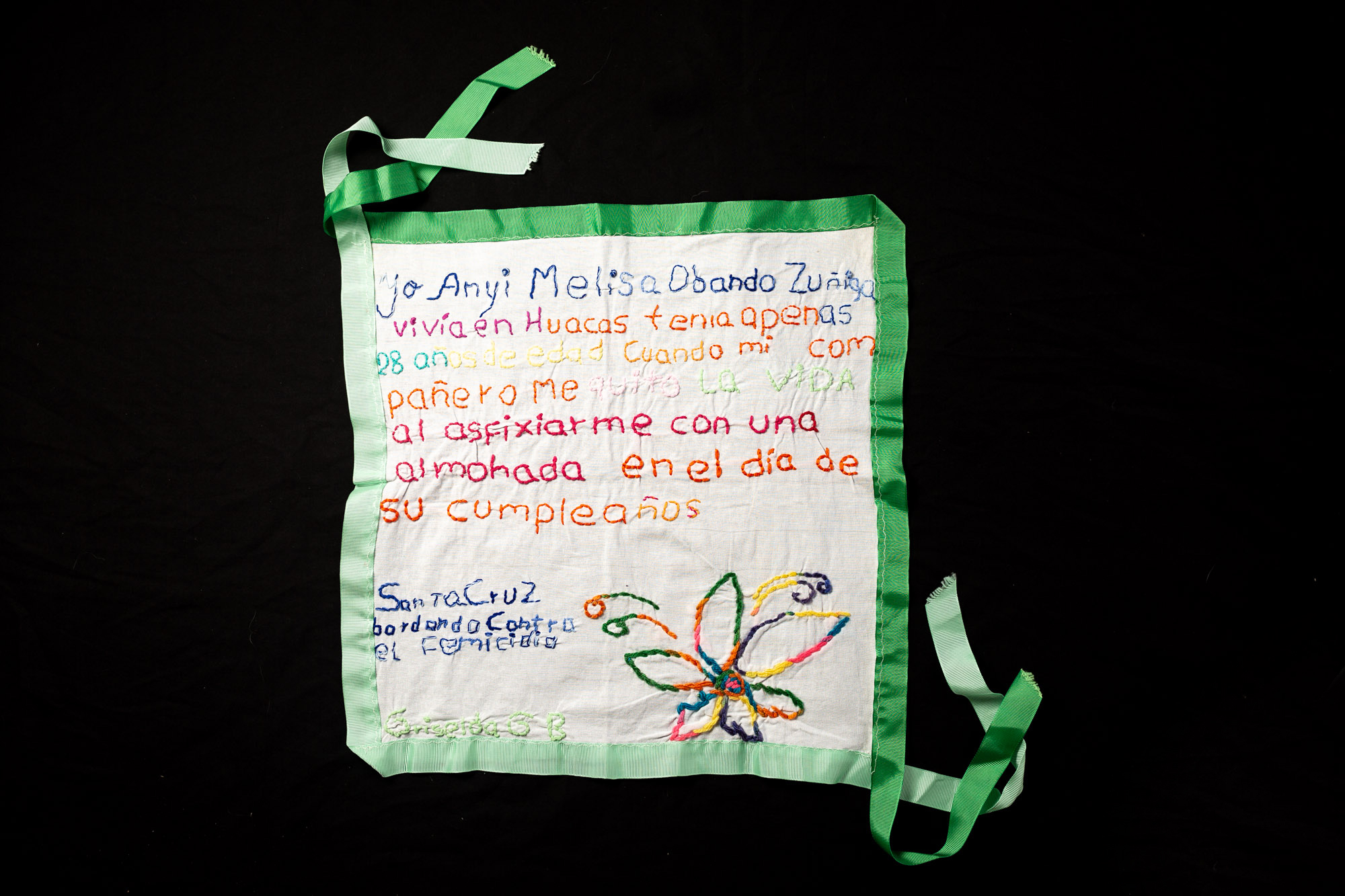

I met Chayo a couple of years ago while marching with a group of women on International Day of Violence Against Women. They were dressed in white, carrying embroideries as if they were banners. At first glance their colorful letters, lace and flowers stood out. But reading one sentence after another, it was impossible not to feel a chill running up your spine. Each of these fabrics told stories of femicides that occurred between 1998 and 2015 throughout the country.

In Guanacaste alone during the last six years there were 25 femicides, and between 2015 and 2017, an average of 4,600 complaints of domestic violence were filed with the courts.

For that reason, these women were demonstrating openly, as if they were leading a battalion, seeking to scare away the wolf pack so that it doesn’t show up again.

I’m Angie Melissa Obando. I lived in Huacas of Santa Cruz, until I lost my life strangled by my partner’s hands. After doing it, he personally sent photos to my family. I was very young. I was just 27 years old. “I never expected my own boyfriend to extinguish my dreams”Photo: César Arroyo Castro

I’m Ivannia Patricia Reyes Navarro. I am 25 years old. I am a mother of 3 children. I was in a relationship for 6 months with the man who killed me with five bullets.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

My name was Sandra Lorena Fonseca Jimenez. I was pregnant when I was killed by my husband. I was 18 years old. He killed me in bed, then threw me into a well tied to a sack full of stones.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Chayo explained to me that she is a promoter for Inamu, the National Institute for Women, and that she was one of the ones in charge of holding workshops for Project BA1, a program of the Central American Integration System (SICA) that tries to prevent violence against women, human trafficking and femicide throughout Central America. Since then, she is one of the trustworthy women of Guanacaste that we turn to whenever we need her help on gender and violence issues.

She taught these workshops for a whole year. They were directed toward women in the communities, representatives of institutions like Inamu, municipalities and youth committees. The women received psychological support, legal advice and help to start their own businesses.

Although the workshops were mostly theoretical, Chayo tried to make them different. She didn’t stand in front of a class reading endless slides, but imparted the contentsto women while doing crafts.

“The idea was that, when finished, they would do something with their own hands. Some of them were women who were told for a long time that they were useless and they believed it,” recalls Chayo.

That’s why she told them every day that they were important.

In one of the modules, women had to creatively visualize violence, through a photograph, murals or posters. They chose to embroider.

When I asked Chayo for those embroideries to photograph them for this photo story, she let go of them as carefully as someone releasing an amulet, along with some requests: take good care of them and ask the souls for permission before handling them. It is impossible to ignore that, on that square of white cloth, the stories of two women coexist: the one who was killed and the one that was able to escape from the circle of violence just in time.

Hi … I’m Melina Calvo Arce. I lived in Tibas. I was a teenage mother. I was 23 when my partner killed me, cutting me with a machete on Saturday afternoon at 5:40 p.m. “Violence took my life” “The one who keeps quiet … Dies”Photo: César Arroyo Castro

My name was Eliette Sanchez. My partner cut my throat in the house where I worked. I was only 23 years old. I was just beginning to live and he denied me that opportunity by taking my life. “Enough is enough; we have the right to live”Photo: César Arroyo Castro

I’m Ingrid Hernandez Mayorga. I worked as a housekeeper to support my children when my ex-partner killed me with a blow to the head and two stabs. My children saw me die.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Transplanting Lives

Chayo relates that for two weeks, the workshop participants transplanted ten stories of femicide onto the fabric with needle and thread. They chose muslin because it is a strong fabric that holds up over time and does not tear or fray easily.

Auria Sandi, a 50-year-old woman from Santa Cruz who participated in the workshops, went to bed every night with the words she embroidered spinning around in her head, and the next morning she woke up remembering them all.

“You could almost feel the pain and anguish of Rocio when thinking about the opportunities she lost, about everything she was deprived of,” narrates Auria, telling the story of a 13-year-old girl who went to live with her 16-year-old boyfriend. After a month and a half, he killed her.

For her and for Chayo, this is a way to heal those wounds, like a suture that binds the two women.

The impact was lasting, says Chayo: they changed a lot emotionally and physically after the workshops. Those who were in circles of violence were able to leave; others continued with their studies and now know more about their rights.

Auria was able to set up her own sewing business and sells custom-made swimsuits. “Aside from being housewives, we can have dreams, fulfill ourselves outside of our home with our own projects,” she affirmed.

The embroideries that run across these canvases can be felt on the fingertips like swollen scars that many women helped to heal. For Chayo, they are an engine that drives her to continue working and compels her to take her message to more people so that not even one more woman is killed. With an air of mysticism and calm, she says with conviction, “Wherever they are, they are taking action.”

My name is Rosibel, 41 years old. I was murdered by my ex-partner at Virgilio Camaño School in Casitas de Nicoya, where I worked as a cook.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

I am Rocio Sandi. I am 13 years old. After a month and a half living together, my 16-year-old partner injured my neck, taking my life. I had high hopes for my life.Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Comments