We arrived at the Las Juntas park in Abangares mid-morning in February. At first glance it looks like any other park with homeless people sleeping on benches, students walking to high school, senior citizens doing their daily duties and green trees that don’t show signs of draught.

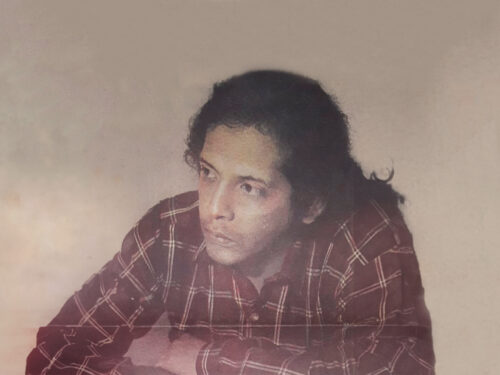

Abangares writer Santiago Porras was born four miles from here in a place called Concepción. He’s skinny, has a white beard trimmed to perfection and behind his thin glasses has a sleepy look of someone who has spent thousands of hours reading.

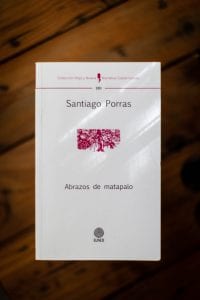

We walked to a bench in the shade to talk about his life, his stories and his most recent book: Abrazos de matapalo.

His new work is a strong critique of bull culture and “the gross chauvinism that Guanacaste is a faithful representative of.” They are critiques that he has been threatened for, he says calmly.

A dozen family members and friends have greeted him while he tells me about how he became Santiago Porras, the writer. They all know that he writes, but, according to him, no one know about what. “People are busy with other things,” he says, unconcerned.

His first contact with literature was in the countryside. “Dad read out loud under a dry tamarindo tree and then recited the novels whole while we dried corn on rainy nights.”

He still has the pieces of anthologies with stories that made him cry for the first time. When he left high school, he didn’t leave a single book unread in the library, though he says there weren’t many. “I was famous for being studious, but I read more than I studied.” That’s how he spent his free time at the University of Zamorano in Honduras. “I read about 100 books a year.” He started a long career as an agricultural engineer, one that lasted until he was 50, when he suffered a heart attack and had to retire.

“I can speak with the impertinence that proximity to death affords me,” says the collector of daydreams, as the author of the Island of Lonely Men, José León Sánchez, called him.

He carries around the six books he has written in his small grey car, which is parked next to the park. It looks like his own traveling bookstore. He has a cardboard box full of his four books of short stories and two novels.

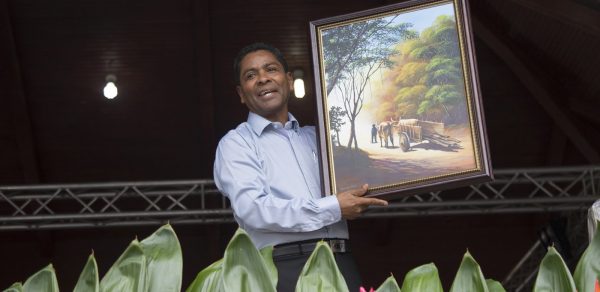

Two of his works are recommended for ninth grade by the public education ministry. Avancari is one, the historic novel that placed him among great Costa Rican authors that tell the story of gold mining in Las Juntas.

Dismembered locomotives and cars rot under the sun of Las Juntas de Abangares. This is the scenario of Santiago Porras’s novel Avancari. Photo: César ArroyoPhoto: César Arroyo

“Santiago Porras takes us by the hand and shows us the mine and its surroundings and speaks of real people that became famous, something that he surely got by exhaustively studying the topic,” President Carlos Alvarado wrote on his blog six years ago.

His intention for writing, he says, is “for people to learn about certain chapters of history that powerful families have hidden from us.”

“During the war in 1948, atrocities were committed and that must be told. You have to go to judicial and national archives, libraries and talk to people. You have to investigate. But in Costa Rica many writers prefer to write stories that they come up with, so they write things that people don’t care about,” he says.

A dusty locomotive next to the park and a and a stone hidden behind flowers are evidence of that industrial mining past in Las Juntas, which is very different than today.

The Metaphor of Evil

A Matapalo hug is the best figure to illustrate the natural beauty of Guanacaste and, at the same time, the oppression of power and chauvinism in the same act. The book Abrazos de Matapalo recreates the life of a Guanacaste ranch while mixing in stories of abuse by powerful men with picturesque landscapes in the province.

The voice that narrates the opening lines of the book is the ranch’s, personified and constructed, Santiago tells me, with remnants of many stories of large homes from La Cruz to Tilaran.

“I’m interested in that fragmented style from different perspectives to cover different points,” says the Abangares writer as the wind blows hundreds of small yellow flowers from the tree that protects us from the sun.

His text moves through several genres and doesn’t use the all knowing omniscient voice. Instead, he gives the voice to characters. They are simple voices that know something about their points of view and are unaware of others. Protagonists are young abused girls or mothers worried about their bull riding children. “Those who could never save themselves form the patriarchal baton,” the back cover says.

Abrazos de matapaloPhoto: César Arroyo

That’s what Abrazos de Matapalo is about: the untold Guanacaste.

“The jerks that have fun with those things aren’t animals too? With the forgiveness of the animals that can’t reason,” asks, for example, a maid in the book.

As though he were another character, Santiago speaks of his life philosophy in questions. Sometimes reserved and others attacking with force against something.

He points to the other side of the park with his finger. “I don’t like that institution,” he says without looking at the church. “Believing and not believing are equal rights. Great atheists have made great contributions to humanity. A hundred years ago we had the same beliefs and people died at 40. Why do people die now at 80 if God is the same?”

Santiago knows that these are controversial topics in the province and that many take pride in their tradition, but he doesn’t. “I am proud that we had a marimba player liker Miguel Torres, a singer like Max Goldenberg or Guadalupe Urbina.”

Of those traditions, his least favorite is bull riders. He says that, while he may not live to see the death of the bull rides, he hopes that it happens some day. “I hope the novel raises awareness among the youth. With the elders, there is no remedy.”

Comments