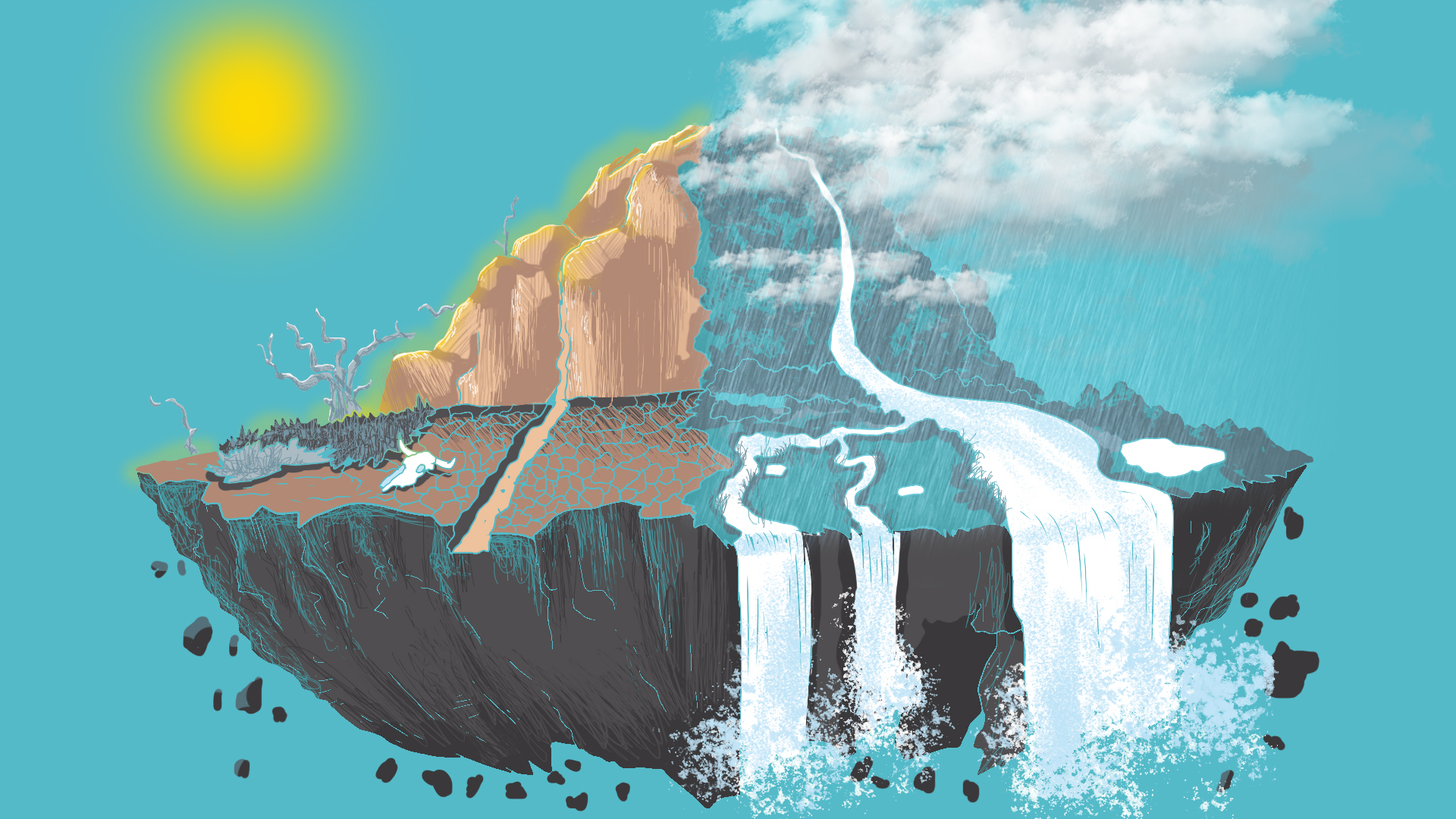

A province of extreme climates. On the one hand, the dry season, with high temperatures and greater aridity in the soil, and on the other, the rainy season, when floods hit some communities harder.

It’s known for its beaches, but it’s actually full of diversity. Mangroves, rivers, waterfalls and species fill every inch of it with natural wealth.

That is Guanacaste, but is it true that climate change will impact all its abundance equally or that the soil will be drier because it will rain less?

With the help of people who are researching the climatic conditions of the province, we address these and other myths, and things that are still unknown.

1. Can we do anything to adapt to climate change?

“If we don’t start acting now, what will become of the generations 50 years from now? If we’re at exactly the same point that we are right now, this will be unsustainable,” pointed out Andrea Suarez Serrano, coordinator of the Water Resources Center for Central America and the Caribbean (HIDROCEC) at the National University (UNA).

There are two sides to the solutions: mitigation, which deals with the causes of climate change, mainly through the reduction of emissions, and adaptation, which addresses its impacts.

That’s where resilience to climate change comes in, defined as the ability of natural environments and societies to cope with the different pressures and impacts caused by changes in climate patterns.

The community of Rosario, in San Antonio in the canton of Nicoya in Guanacaste, is an example of how this is possible. Community members decided to come together to bring about a miracle: this year, the Mata Redonda Lagoon didn’t dry out completely, something that hasn’t happened since the 2014 drought hit the province.

The Voice has told you more stories of resilience, too, like the story of a group of women who came together to restore a mangrove in La Cruz and the one about two projects in Guanacaste that are concerned with redrawing the rainforest of the sea that is about to disappear.

2. Are phenomena like El Niño caused by climate change?

Climate change can be natural or anthropogenic (caused by humans), but specialists tend to focus on the latter when defining the concept of climate change.

So while it may be tempting to associate climate change with El Niño, it’s imprecise to do so because it’s a natural phenomenon.

“El Niño is associated with droughts, and it’s common for people to confuse it with climate change, when in reality, it’s been there for thousands of years,” explained Hugo Hildalgo, director of the Center for Geophysical Research (CIGEFI) at the University of Costa Rica (UCR).

To the contrary, there isn’t enough evidence regarding how climate change will impact El Niño.

Although climate change might manifest itself in the future with this phenomena occurring more frequently and more severely, the reality is that this hasn’t been proven yet. “It will affect it, but the relationship isn’t that simple,” said Hidalgo.

3. Do we see “normal” climate behavior each year?

When we talk about dry or rainy season in the province, climate variability is a reality.

This concept refers to fluctuations in the climate, but historically, not in a specific event, according to researcher Pavel Bautista, from UNA’s Mesoamerican Center for Sustainable Development of the Dry Tropics (CEMEDE).

Bautista is part of a group that studies the coastal communities of Cuajiniquil, Santa Cecilia and El Jobo in La Cruz in Guanacaste. As part of the research, the team conducted a survey on climate change concepts and found that people who live in those areas of Guanacastecas repeated the phrase “normal year.”

“We can’t talk about a normal year, when that doesn’t exist,” said Bautista. “People perceive and remember a lot about extreme events and remember the recent drought, which occurred from 2013 to 2016, more or less. So, they talk about the rainy season starting in September, but it doesn’t happen that way every year. In reality, that varies every year.”

Credit: Dunkan HarleyPhoto: Dunkan Harley

4. Is less and less rain falling in the province and is that why it will be drier?

Guanacaste is more arid than the rest of the country, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t rain in the province or that the rainy season that hits the province has diminished. In fact, annual rainfall shows a very similar behavior from one period to another. What happens is that the rain is distributed unevenly throughout the year.

In Nicoya, precipitation reaches 2,000 millimeters (about 79 inches) a year and in Cuajiniquil in Santa Cruz, 1,800 millimeters (about 71 inches), data that isn’t insignificant according to studies by the UCR’s CIGEFI.

Although the rain pattern hasn’t shown significant changes in Guanacaste, its land does show greater aridity.

Droughts are very common in the province, but every ten years, they last longer, pointed out the director of CIGEFI, Hugo Hidalgo.

What has a bearing on the region being drier? It’s not just El Niño. It’s also the trade winds and the ocean’s surface temperature.

The temperature has indeed increased and will continue to do so as a result of climate change. As there is a greater demand for water from the atmosphere and there isn’t increased rainfall to compensate, the ground becomes more arid.

Guanacaste will have drier conditions in the future, but not because of less rain, Hidalgo explains, but because the temperature will continue to rise.

Rainfall will show relatively small variations in the province, while changes in temperature will be significant, according to CIGEFI, as part of studies within the framework of the Integrated Central American Dry Corridor Program (PICSC).

The water supply, the replenishment of aquifers, water for agriculture and for the environment will be reduced by the increase in aridity, and as the ground becomes drier, forest fires increase, said Hidalgo.

5. Does water usage in agriculture and industry affect the province?

“Water is getting out of hand,” stressed Suarez, from HIDROCEC.

Suarez is part of a project that HIDROCEC is working on jointly with the Technical University of Dresden in Germany, and the National Groundwater, Irrigation and Drainage Service (SENARA), to develop a model that will make it possible to estimate water availability in the Huacas-Tamarindo micro-basin in Santa Cruz. The analysis is based on the wells monitored by SENARA and they are already obtaining some results.

“As a result, we had quite a few scenarios at 25 years, at 50 years, and the worst scenario is that we’re going to have a water deficit and that’s not a lie,” he explained.

He added that “it’s no secret to anyone that [the wells] have been and are being overexploited and that, due to the drought, the levels decreased to such an extent that we had salinization of wells. There are wells both in Brasilito and in Tamarindo that were taken out of use because they were salinized.”

What can be done about it? For the province and the coastal areas, it is essential to opt to use surface water, reuse water for crops and production and not depend so much on groundwater, “not to think about extracting more water from the Tempisque River because it’s no longer sustainable,” said Suarez.

6. Is there still time left before climate change impacts us?

We may see climate change as a very distant issue, but climate variability is knocking on our door.

Hydrometeorological events such as droughts, hurricanes and tropical storms hit the province more frequently and with greater force.

In recent years, studies indicate that there have been periods in which we experience the effects of El Niño or La Niña closer to each other, Suarez indicated.

These fluctuations in the climate become evidence of climate change when they are studied over a long period (even decades) and show statistical variation during that time.

Even though Guanacaste registers a very similar amount of accumulated rain each year, “the way it rains does seem to be changing. Extreme events are becoming more and more extreme. It might not rain much more in a year, but when it does rain, it does so torrentially,” said Hidalgo from CIGEFI.

According to the National Meteorological Institute (IMN), some scientists agree that the effects of interannual climate variability are mixing and strengthening with the impacts of climate change.

Worldwide, there is solid evidence of the effects of warming in the atmosphere.

7. Climate change will affect everyone equally

Climate change impacts some areas of the province with greater force and climate change will hit the areas that humans exploit the most first.

The canton of La Cruz faces one of the harshest realities. There, we have coastal aquifers that have faced increased threats and vulnerabilities as the years pass, said Suarez, from HIDROCEC. Why? Tourism and urban development in the region is causing overexploitation of some of these resources.

Climate change goes beyond an environmental factor, It also affects societies, their economy and their production.

In the province, climate fluctuations are having a distinct impact on six areas: livestock, agriculture, fishing, tourism, community and water, according to evidence from CEMEDE.

For tourism, lack of rain isn’t seen as something negative because business is stimulated. It’s completely the opposite for economic activities that need rainfall to develop, for example agriculture, explained Bautista, from CEMEDE. “They refer to how the climate in La Cruz makes it hard to carry out these activities,” he added.

At the global level, institutions such as the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) affirm that climate change will continue to cause more extreme weather events, such as land degradation and desertification, water shortage, rising sea levels and temperature changes, “all of which will make the rural poor the first victims, hampering efforts to feed the whole planet,” the organization noted.

The myths surrounding climate change are many, and researchers’ findings indicate that the Guanacaste population is learning about the subject, but the misinformation gap is deep.

Bautista affirmed that in their research, they’ve noticed that “people [in Guanacaste] recognize climate change but not the reasons why this is happening or what they can do to adapt.”

Comments