My godfather had the wonderful habit of giving me ¢500 ($1) every time he saw me. Freddy, the general store owner (pulpero, in Spanish), helped me stretch that orange bill so I could fill myself with happiness: cookies, ice cream, Del Angel dulce de leche, and change in bubble gum. I met Freddy when I was three years old. He saw me cry because my dad wouldn’t let me have a box of milk and he watched me buy my first package of Viceroy cigarettes at age 14. He knew me so well that he could guess what I came to buy, and with that profound knowledge of his customers he supplied his business: he and his general store were always there on that corner for my neighbors and me.

General stores and what they have inside are a graphic explanation of their neighborhoods’ consumption habits and they couldn’t exist in any other form.

Read also: Great Confidantes Called Bartenders

The Spanish name for a general store, pulpería, is only used in Central America and no one knows exactly where it comes from. According to architect and historian Andrés Fernández, the are only two explanations for the origins of the word, and they are both pure speculation: One is that it comes from the Spanish word pulquería (a type of tavern that serves pulque, a fermented drink made from the agave plant) or that it comes from the Spanish word for octopus, pulpo, because the storekeeper at a pulpería must work as if he had eight arms.

According to Fernandez, the origin of the pulpería in Guanacaste isn’t clear, but it’s known that they existed in the last 25 years of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th and sold groceries and other supplies. In more remote areas, it was the only place where families could do their daily shopping and buy everything they needed: string, buckets, brooms, and dustpans.

See also: Photographer Portrays Guanacaste in Short Film “Amor de Temporada”

In the most remote towns pulperias continue to be a place not only for buying and selling, but also for social gathering; a place to meet and gossip. On pulperia benches we sit and watch, to see and to be seen, and to find out what’s going on around town.

Pulperias are disappearing, losing ground to chains and larger grocery stores, and finding them wasn’t easy. In towns with higher levels of economic growth we were given lots of clues as to where we could find some of the oldest and most emblematic pulperías, but many of the addresses we were given were no longer pulperías. They were closed. Conversely, in the most remote areas with smaller economies, they are still the place to do daily shipping and chat.

Sell me $1 of cheese. In 1956, Francisco Moraga bought a television. He placed seats in the living room of his house and and set up a space where people could come and watch it. It was the first television in Buenos Aires de Santa Cruz and he charged customers a penny to come and watch TV. They left it on until people were gone. Francisco’s wife, Mrs. Raimunda Gutiérrez, decided to sell ice cream, and thus began “Mrs. Munda’s Pulperia,” as it was known in the neighborhood. Four years ago, Francisco and Mrs. Mundas’ grandchildren, Lidia and Hector Briceño, took over the business

What will this buy me? When they started their business, La Esquina, it was one of the only places to shop. There were no supermarkets or larger stores in Sardinal. According to the owner, things have changed a lot. It’s difficult to keep such a small business open and compete with lower prices at large chains. Their business stays open thanks to smaller sales and a family-like customer service.

Do you have frozen soft drinks? Rural Pulperías are like stamps from the past; A past when you bought five pieces of candy with a penny and a large soft drink with two pennies.

How much for the pill?According to Justo Luis Barrantes, this is the oldest house in San Jose de Pinilla. His wife’s uncle, Serafín, built it to live in. He later turned the part closest to the street into a pulpería. Justo has owned it for 30 years. He bought it with a loan from the extinct bank Banco Anglo. When he opened the store, he could only transport merchandise via car in the summertime. When the winter rains would start he had to use a cart pulled by oxen because the river would rise.

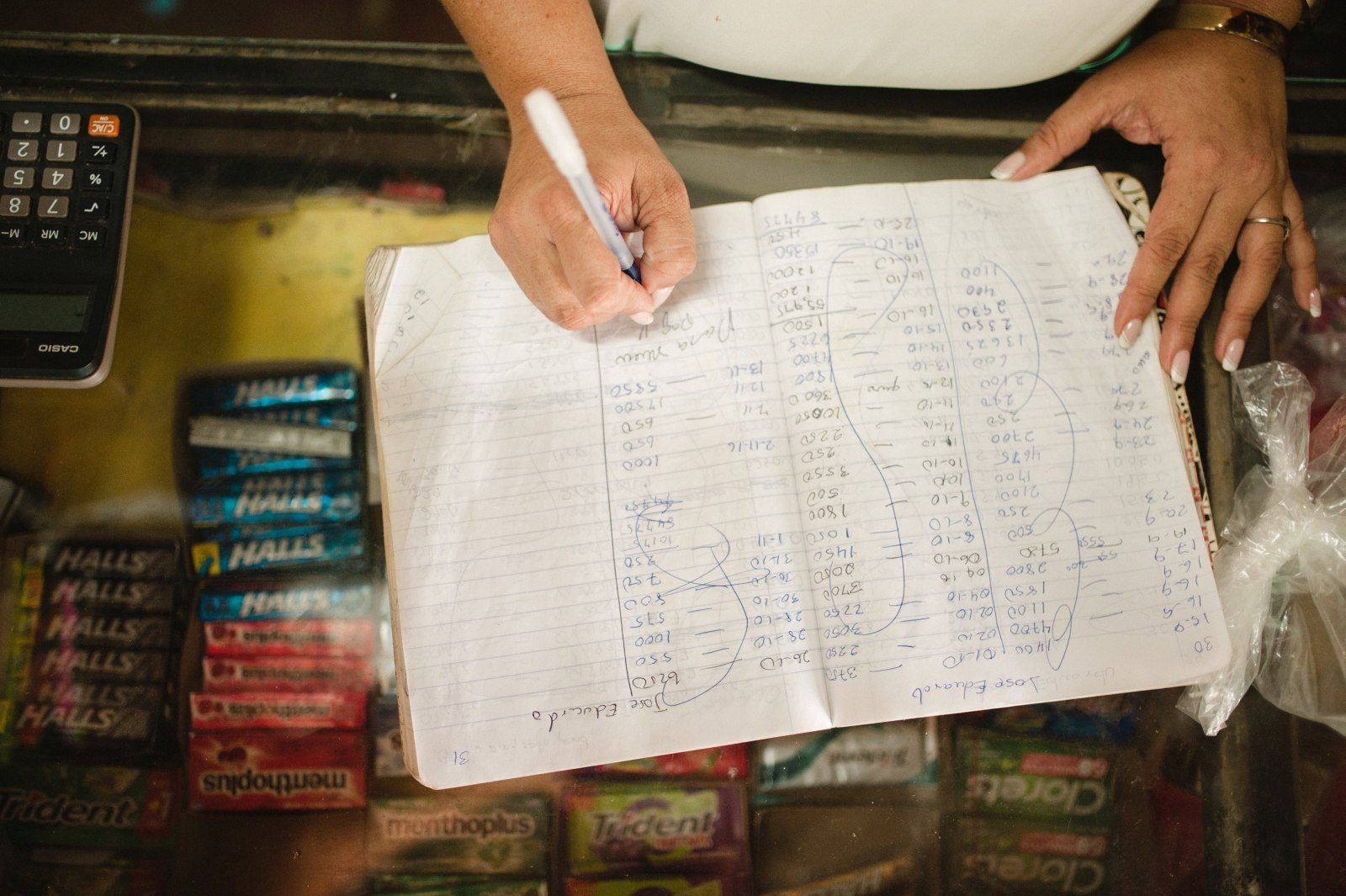

Can you put it on my tab? Some things have changed a lot at the pulperías, but the method of opening a tab where storekeepers jot down small debts in a little notebook is still a mainstay, says Lidia Briceño. Customers leave whenever they can: an honor system is a necessity that both the customer and the owners need: It’s better to sell on credit than not sell at all.

Comments