At seven years old, Mich Coronado loved playing soccer with their dad in the plaza of San Miguel, a small town in Cañas. And when Mich saw the soccer teams in their uniforms, with cleats and shin guards…

“I used to say to daddy, ‘I want to play with them. I want to wear a uniform,’” but Mich’s father ended up explaining that the teams were only for men. “But what’s wrong with it? I play just as well with them,” Mich would tell him.

Mich’s father, then, spoke with the coach to let Mich join one of the teams. And he agreed to it, but then another obstacle came. Mich wasn’t allowed to register for the town tournament because they didn’t allow mixed teams. Mich’s father, mother, and coach talked to the sports commission. “One fight after another, we succeeded,” they recalled.

Mich chose this memory to illustrate the perfect description of what their family was like. “I come from a home with a lot of love, respect and education. My parents were always in all aspects of my life.” That’s why it was so hard to distance from them in 2017, when Mich told them about Mich’s nonbinary sexual orientation and they didn’t take it well.

Mich moved to Liberia.

It was a little bit to mark a distance that would allow us to think and to heal,” Mich says. Was it an unattainable dream to imagine them fighting side by side together like they did so Mich could play on soccer teams?

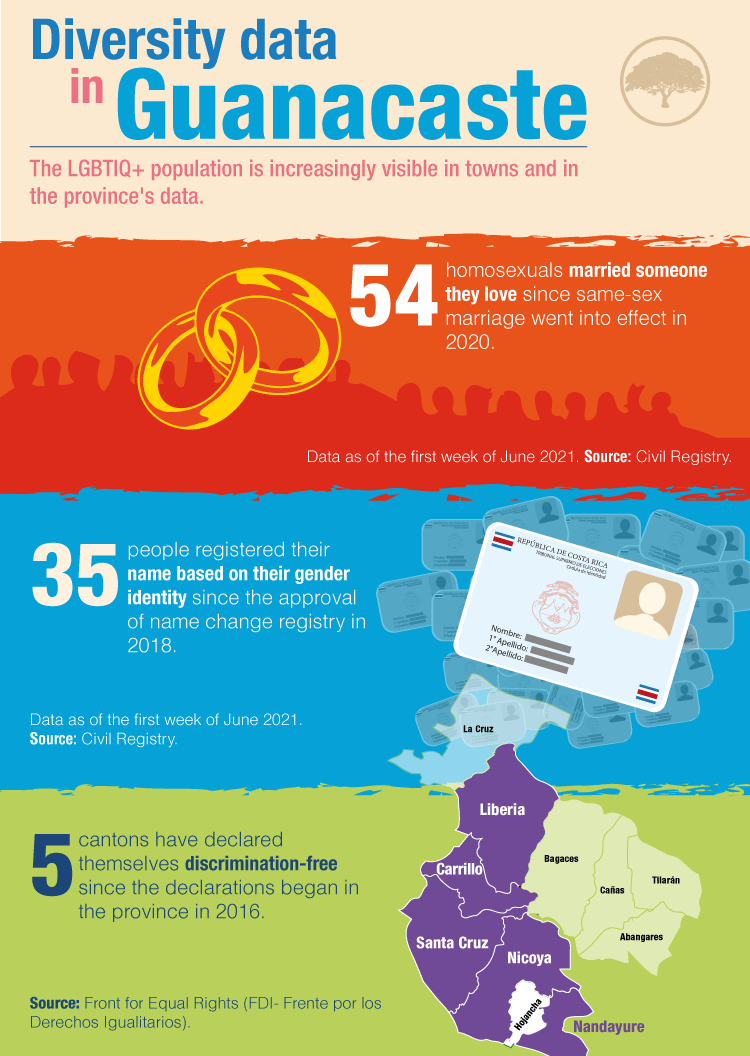

Even in 2021, LGBTIQ+ people in Guanacaste want to migrate to Liberia or the central provinces of the country as an option for freedom since most towns in Guanacaste don’t have programs for sexual and gender diversity education, and accepting it is still a distant milestone for communities.

“Going to the Greater Metropolitan Area (GMA) is an idea that [sexually diverse] people from town grow up with. Since I was in high school, I started saying, ‘I keep quiet here. I’ll never, ever say that I like women because I already see how they treat my gay friend or my lesbian friend,” said Ana Maria Murillo Varela, a lesbian and activist from Tilaran. “I always thought about escaping from Costa Rica, not just [going] to San Jose,” added Sebastian, a trans teen.

Vitinia Varela and Adolfo Murillo proudly raise their heads high for Guanacaste’s sexually diverse population. Two years ago, they founded Amor a la Diversidad de Tila (Love of Diversity of Tila), a group of sexually diverse people and family members with the goal of reaching the milestone where the communities of Guanacaste finally respect— and hopefully support— the LGBTIQ+ population.

Mom and Dad’s Hug

Living in Liberia at the age of 23, Mich still felt very lonely, not knowing anyone there, and struggled with guilt, thinking about hurting their family. At the end of 2019, Mich attended an activity organized by the “Yes, I Accept” campaign to provide information about same-sex marriage, which would become legal in less than a year. Mich had never before participated in a sexual diversity activity, much less talked about their sexual orientation with strangers. Being there was terrifying.

They talked about the legal aspects of same-sex marriage, what changed and what didn’t. “They put on a very beautiful activity,” recalled Mich. Beautiful but difficult: “We had to talk about our families, but I couldn’t and I started to cry.”

At the end of the activity, a couple approached Mich to ask if they could hug. It was Vitinia and Adolfo, who, together with their daughter, Ana Maria, had starred in one of the campaign videos that reflected on same-sex marriage from family love.

Vitinia invited Mich to participate in Amor a la Diversidad de Tila. “It was just what I needed at that moment,” said Mich. “I had that small sense of self-pity towards myself of saying ‘I’m not okay and I need help.’ And I think that is extremely difficult, more so in situations when you feel like everyone pushed you aside. “

In Guanacaste, only two more groups support sexually diverse people: the regional branch of Transvida, coordinated by Barbara Fajardo, which supports trans people, and the Guanacasteca Diversity Collective, co-founded by Alexander Rosales, which organizes activities to reflect on diversity in Liberia. In San Jose, the number of groups might exceed 20, according to a count on social networks.

“These programs are so important,” emphasized Rosales, who co-created the group in 2015, adding, “They are a window for the [sexually] diverse population of the entire province to know that there are places that can embrace them.”

That’s what Mich felt when he went to Amor a la Diversidad de Tila. “It was very nice to feel that there are people who are in the same struggle, and who are from here in the province.”

A Place to Be Free

Vitinia and Adolfo founded the group after many years of personal development, after learning of their daughter’s sexual orientation.

“It was a hard process at times, smooth at times, because I accepted my daughter without buts. I told her that I loved her and respected her and that I would always be with her,” Adolfo recalled. “But I entered a denial and I thought about what family members or coworkers were going to say about me… In other words, I was being selfish. I was thinking about me and not about her.”

Sitting around with their arms crossed wasn’t a possibility with the affliction they felt, so they looked for help in 2015. “At that time, I went to San Jose because in this area, there’s nothing [to learn more about gender identity or sexual orientation],” Vitinia said. But of course, she had the intention, the time and the means to do it. “So there was always that little itch, that concern that in this area, a group had to be opened for the whole family.”

In November of 2019, they held the first meeting of Amor a la Diversidad de Tila at their home in downtown Tilaran.

Those who showed up turned out to be people as diverse in age as they are in sexual and gender identities and orientations. A grandma of a trans teenager. A mom of a trans boy. Two trans teens. A lesbian woman who later brought her girlfriend, Paula, to the group too. Mich, who is a non-binary person— someone who doesn’t identify as female or male— and Mich’s girlfriend.

To Mich, transforming towns so that they accept diversity should be a loving and caring process. They put it this way. “Let’s do it buffet-style in the province, where we put all the teaching on the table and people who are hungry and want to eat, grab what they need most: sex education, information about HIV, knowledge about non-binary gender…, because it would be so nice if the people who come after us don’t have to suffer as much. The only thing we want is to be happy, like the purpose of every person in this world.” Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Together, they healed the afflictions in their hearts and educated themselves on sexual diversity issues.

Since March of 2020, due to the pandemic, their meetings became virtual. That has opened up a window of possibilities for them: families and people from outside of Guanacaste joined in and they have talks with experts from other provinces and other countries.

They also started holding two meetings a month, one for training on diversity issues and another to share what wrenches their hearts and what makes them happy.

“Some people in the group said that we needed two meetings a month, one with a specialist and the second with the group, because we are going through a pandemic that left some people without work; others had no choice but to return to their parents home, where they had been mistreated, because the universities closed,” related Ana Maria.

It’s a never-ending learning process. Homosexual people who learn about trans experiences. Moms and grandmas that begin to understand their loved ones. Trans people who listen to a non-binary person. In addition, they learn about gender-neutral language and intersectionality of the diverse population of indigenous peoples.

Flora, the grandmother of one of the trans teens, said she ordered herself to attend. For the rest of her family, it has been impossible to embrace the diversity of her grandson, mainly because of their religious beliefs. What would happen to him if she didn’t embrace him?

“Suicide could result from such a huge rejection of these people, and I don’t see the sense [of why they reject or discriminate against them]. They are people the same as everyone, and I think that they are equally loved by God,” said Flora. “If I disagree with people who reject them, could it be that I’m a modern grandmother?” she wondered.

The trans boy’s parents’ rejection of him due to religion isn’t an isolated case. A good part of Christians still mark and exclude sexual diversity. “I feel like it’s more political than anything else,” Vitinia said. “And that’s not the god I believe in, who is a god of love,” she added.

The Catholic Church, which directs the official religion of the country, has openly shown its opposition to same-sex marriage, which became legal in 2020, as well as to changing names according to gender identity, since 2019, and even to sexual and affective education in schools, discussed mainly in 2018.

Beyond changing regulations, laws and decrees in favor of sexual diversity, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights itself has highlighted the need to raise awareness from the standpoint of culture, religion and tradition as well.

Even groups like Espacio Seguro Católica – Costa Rica (Catholic Safe Place – Costa Rica), a Catholic meeting forum where “LGBTIQ+ people can feel complete freedom and security to express their faith without fear of being judged, excluded or discriminated against due to moralistic arguments,” have arisen from the unstoppable need to respect human rights regardless of identities or orientations.

“It’s that they continue believing that diversity is a bad thing. It’s generally believed that the [sexually] diverse person is a perverted person because it’s believed that everything is based on the genitals,” Vitinia commented. “Just that, sex. But that’s not what identifies people, nor is it their worth. We are a conglomerate. They also have life projects and they fall in love,” she explained.

Religion tore Adri apart. She wanted God to tear out that piece of her, because she believed it was a sin to fall in love with women. “It was a process of denial all my life. I said, ‘No one is ever going to know this. No one ever,’” she repeated to herself for at least 20 years, convinced that she would pay for it.

I remember crying thousands of times in the most holy of my town, telling God why did I have something so ugly, that I hadn’t chosen it. I asked him to take it away from me, to come in some way and tear that piece out of me,” recalled Adri.

Until she moved to Liberia in 2008 and found the little bit of openness back then. First, she told her best friend and then other people she was close to, including her dad. “I expected the worst reaction from him, but he put his love for me first and told me, ‘You are perfect. I love you as you are.”

That’s why she was also so moved when she saw the video of Adolfo, Vitinia and Ana Maria in the “Yes, I Accept” campaign in 2019. “Especially listening to Mr. Adolfo touched my heart so much. I cried because I saw that there was so much love there.” And when Adri found out that the couple in the video started a group, she knew she should be there. “I knew that I wanted to be in that meeting because it was changing the history of Tilaran in some way.”

Paula Cespedes joined the group Amor a la Diversidad de Tila after meeting Adri, who is now her girlfriend. It took her more than 20 years to accept herself. “I remember many nights crying because I didn’t want to have this, but what has changed since then? What has changed is my acceptance, not how people see me,” she reflects. One of her most desired steps is to talk openly with her mother about her sexual orientation. “She knows where I am. She knows that I’m with my girlfriend. And even though we don’t talk about it yet, she supports me and I can feel it. And I know, I hope it’s not the opposite really, but I can feel that she loves me and will support me. I know it’s a process and I’m being patient, but I’d like to include her in this part of my life, with Adri, who is the love of my life.” Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Be Visible

After existing for more than a year, the group is clear that one of its main objectives is to work to soften the path of those who come after them, so that it’s smoother than theirs.

“They’ve wanted to erase us from the map of how to be the Guanacaste person from a rural family, but now we want them to see that we are a large group, that we are working, that we are happy and that they will no longer make us invisible,” said Ana Maria, who counts more than 40 members of the group.

Mich sees it this way: “I always tell the group that we are superheroes, because just by seeking help, we saved our own lives. Now imagine what we can do if we take that information to save more lives.”

To save or to know that they live happily. The intention, in the end, is to enjoy one’s brief life with the ones that each one loves. “I consider myself very open, because I have my sister who is gay and I always considered that these issues weren’t at all complicated for me,” said Ligia, Sebastián’s mom. Until she found out that her son was also a trans person.

“Now I realize that I was drowning in a glass of water. How each person feels and how each person identifies is something so personal, that now I’ve overcome it. I know that seeing my son happy is the only thing I need,” said Ligia.

For Sebastian, her 18-year-old son, having the full support of his parents changed his life. He now feels the freedom and the courage to talk to them without fear. “I even know cool people, groups and so on, and I still want to leave Costa Rica, but not to live, rather as a trip.”

Sometimes the scenario crosses Vitinia’s mind in which she and Adolfo leave the group to make it a group only for sexually diverse people. “I was educated in a group mainly of moms, and I didn’t feel ready to be among young people, which the majority are,” said Vitinia.

She has even commented about the idea in the group, to which everyone gives the same reply: the group would lose its essence without them. That’s why the group now sees how key it is for family members and sexually diverse people to work together to build a Guanacaste that is more open to diversity.

On the one hand, Vitinia and Adolfo believe that their daughter and all the diverse people came to rescue them from ignorance. “Today is a new dawn with my daughter. Every day is happier because through her, I have more sons and daughters than we’ve found in this group of Amor a la Diversidad de Tila,” said Adolfo.

On the other hand, for those who make up the group, being without them would be like being left without the mother and father who fill the gap of family for some.

“I believe that if my parents had supported me like they did at that time, when society told us that women couldn’t play with men, I would have avoided I don’t know how many years of suffering, doubts, guilt and thinking that by being the way I was, I was hurting my family,” said Mich.

“I think I would’ve taken on the world.”

Comments