Tamarindo representative Aderita Rosales is sure the district she is from pays the most taxes to the canton. “I think it’s always been that way,” she says. But, until this year, she had no way to prove it.

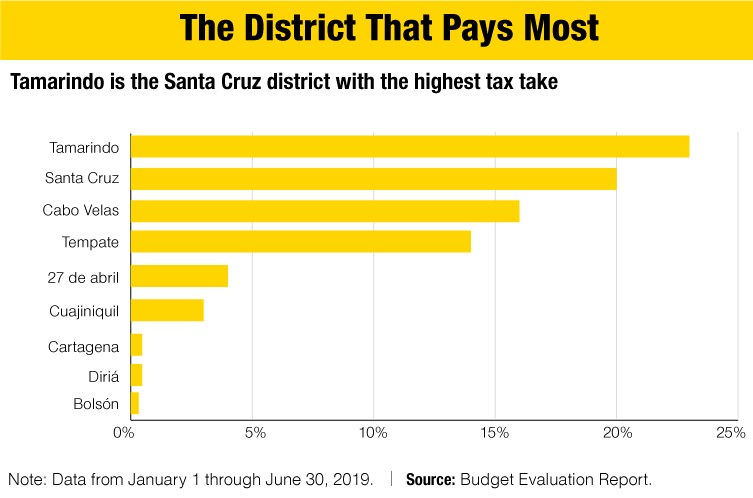

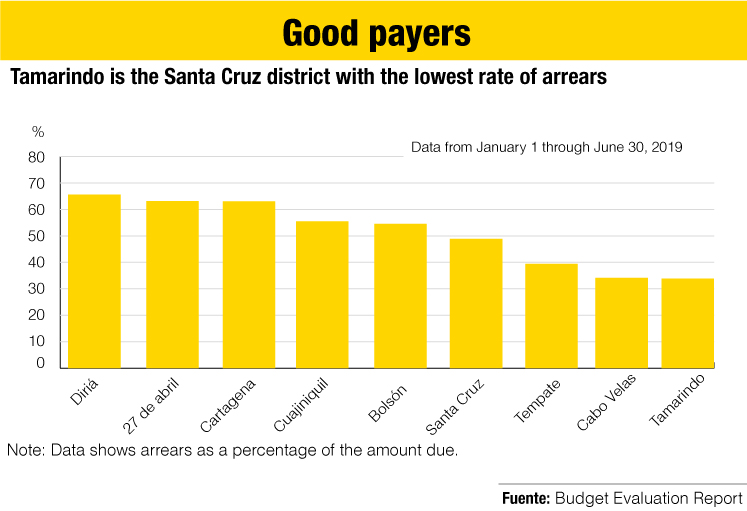

For the first time, the City of Santa Cruz explained in greater detail how much money each district in the canton pays to municipal coffers with data from the first half of 2019.

Between January 1 and June 30, 2019, businesses and residents in Tamarindo paid nearly $2 million in taxes such as real estate tax, trash collection tax, patents and construction taxes, among others. The number represented 23% of the city’s total revenue. It’s the highest percentage of all nine districts in the canton.

While it’s only half the year, authorities estimate this trend has existed for at least a decade.

The money paid by the coastal district is more than the central canton of Santa Cruz, even though Santa Cruz has three times as many people. According to the National Statistics and Census Institute, Santa Cruz has 26,134 people versus 7,442 in Tamarindo.

Investments in tourism are the most immediate explanation for understanding why it pays more because, among other things, it directly impacts property values and that “ends up reflecting itself in the payment of more taxes,” according to city financial director Mario Moreira.

An example to better understand this is that a lot of 2,000 square feet located in the area with the highest property values in the district of Santa Cruz (the business zone) is valued at $63,000 and pays annual real estate taxes of $160, according to the city’s property appraisal department.

That same lot, with the same characteristics in the best part of Tamarindo increases to $100,000 and would pay $250 a year.

But, the fact that Tamarindo pays (or has paid) more money to the city doesn’t necessarily mean that it receives more projects or services, and that upsets community representatives.

“Historically, reinvesting resources in the district hasn’t been done well and that is visible in the backlog of infrastructure projects in the community,” Tamarindo’s Association (ADI) wrote in a letter sent to The Voice of Guanacaste.

For representative María Eugenia Alfaro, other problems have also been left unresolved such as security along the coast.

We can do more from city hall. There are a lot of weaknesses that aren’t new. The issue of drugs, for example. We should crack down harder on it. We have a long way to go in that respect,” she said.

There is no law or regulation that requires the city to re-invest in a canton according to the percentage of revenue it contributes. So, investing in Tamarindo depends on the vision of the local government and the city council.

For example, between 2012 and 2016, the city budgeted $580,000 in projects for the coastal district. For the central district, it budgeted nearly three times that amount, according to estimates by this newspaper using city budgets for each year. The analysis considered the projects listed in the city’s investment program (called Program III within the budget).

Deputy Mayor Iván Ramírez recognized that Tamarindo hasn’t received the equivalent of what it has paid, but says that at least in the last two years there has been a better injection of resources from the local government.

Maybe people don’t see it because they only see what happens downtown, and not everything in the communities that make up the district,” Ramirez said.

An analysis by the director of city rural and urban development Diego Rodriguez, of which The Voice of Guanacaste obtained a copy, counted at least $350,000 invested in the district between 2017 and 2018.

The city used the money to pave the road between Tamarindo and playa Langosta with $170,000, build a water runoff system along the same road with $165,000, and build a lifeguard tower in the public zone of Tamarindo beach with $9,000.

Another of the city projects is the donation of a property for the construction of the first police station in the area.

Causes and Excuses

The main reason explaining the “low retribution” mentioned by those interviewed is poor planning. City officials like Moreira agree, as do city planner William Huertas and district representatives.

Economic planner for neighboring Carillo, Mauricio Mejicano, says that the city of Santa Cruz could start to review its resource redistribution model.

“I’m talking about cities seeking out a model of distribution that looks at several variables, like land extension, number of residents and the Human Development Index. I’m talking about clearer policies for assigning resources,” Mejicano said.

Huertas, the city planner, adds that the lack of planning starts with poor project design, which is often presented by district councils. Some, for example, come to the council without a clear financing plan.

In 2017, an investigation by The Voice of Guanacaste showed that the City of Santa Cruz didn’t spend $140,000 on budgeted projects that were poorly designed for at least three years and didn’t comply with the minimum requirements to spend the money.

“Often times what happens is that we try to strengthen the areas that have the least to balance out development in the canton. It’s an issue of solidarity. But we still owe [Tamarindo]” Huertas said.

Moreira says the city should focus on strengthening other districts that also generate wealth for Santa Cruz. In the district of Bolson, for example, those who paid the least to the city, with a contribution of 0.32% in the first half of the year, stand out.

“The municipality hasn’t encouraged Bolson’s development. If the city invests, it will receive more in return. That’s the reality of business. But now, instead of having a virtuous cycle, we have a vicious cycle,” Moreira said.

Comments