Alfonso Bustos crossed the forest along the paths that he and his father made in order to get from one tree to another.

We had no land, so we rented the trees,” Alfonso wrote in a short text in which he narrated that brief chapter of his life.

He and his father came to Guanacaste from Nicaragua in the mid-1900s looking for a specific tree, one from which they had learned to make a living. This tree is known in Latin America as the balsam of Peru and in Costa Rica as chirraca or simply balsam (Myroxylon balsamum).

The balsam harvesters or balsameros, as they and the other twenty people with whom they came were called, arrived in a province of large haciendas staking their future on expanding pastures and raising cattle.

They, on the other hand, placed their bets on the sap of the balsam trees, which they found in the mountains of La Garita in La Cruz, in Quebrada Grande of Liberia and in San Jorge of Bagaces. Although the tree was found in other parts of Costa Rica, the trade mainly developed in the Chorotega Region.

They made medicines, used it as a salve to heal wounds and as a cure for bronchial illnesses and an endless list of other ailments. It wasn’t a notion of the last century. It was the ancestral medicine of indigenous peoples and it was also the sacred oil that the Catholic conquistadors used in their ceremonies.

It was so popular that between 1560 and the end of the 16th century, it was the second most important export product in the “Kingdom of Guatemala” (made up of the provinces of Honduras, El Salvador, and Costa Rica-Nicaragua at the time).

The balsam was exported by boat mainly from the coasts of Guatemala and El Salvador to the port of Callao in Peru. From there, it was distributed to Spain as if it were a Peruvian product. Hence the name balsam of Peru.

How did it die out after being key to the local economy?

Illustration of the balsam tree included in a German medicinal guide originally published in 1897 by Hermann Adolph Koehler

The New World Panacea

Almost five centuries before Alfonso set foot in Guanacaste, in the year 1570, Francisco Hernandez, a physician and historian from the Spanish kingdom, sailed to the “new world,” where he compiled an extensive record of the Mexican territory’s natural history.

Hernandez collected a large amount of data and knowledge with the help of indigenous doctors. In his documents on the Natural History of New Spain, compiled by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), he mentions the benefits of a “balsam of the Indians” that the native peoples called hoitzilóxit.

Making incisions in the bark or in the trunk of this tree, that precious liquid is distilled, which is famous all over the world, and not yet praised enough, which they call balsam,” Hernandez wrote.

According to his texts, drinking this balsam was useful for “warding off and combating innumerable kinds of illnesses” such as “impurities of the kidneys and bladder,” or preserving “youthful vigor for a long time.” As if that weren’t enough, the Spaniard claimed that if people apply it as a cream, “it solves tumors and strengthens the brain.”

The entire region benefited from the tree because it was found from Mexico to Brazil. People continued taking advantage of its sap for centuries. It even came to be considered the black gold of El Salvador.

In the late 1800s, a new gold rush pushed a Salvadoran family by the last name of Serrano to cross borders in search of more trees. So they arrived in Nicaragua and met up with Alfonso, his family and his community. At the beginning of the 19th century, balsam was declared the national tree in El Salvador.

The Long Road to Sap

According to Alfonso’s memoirs, the family bought some land rich in balsam and the farmers and laborers from nearby areas learned the resin extraction technique from them. His father was among them.

Later, they decided to come to Guanacaste. Alfonso didn’t specify their reasons for migrating in his memoirs. What is clear is that they looked for the balsam trees here to continue working in what they had learned: extracting its sap.

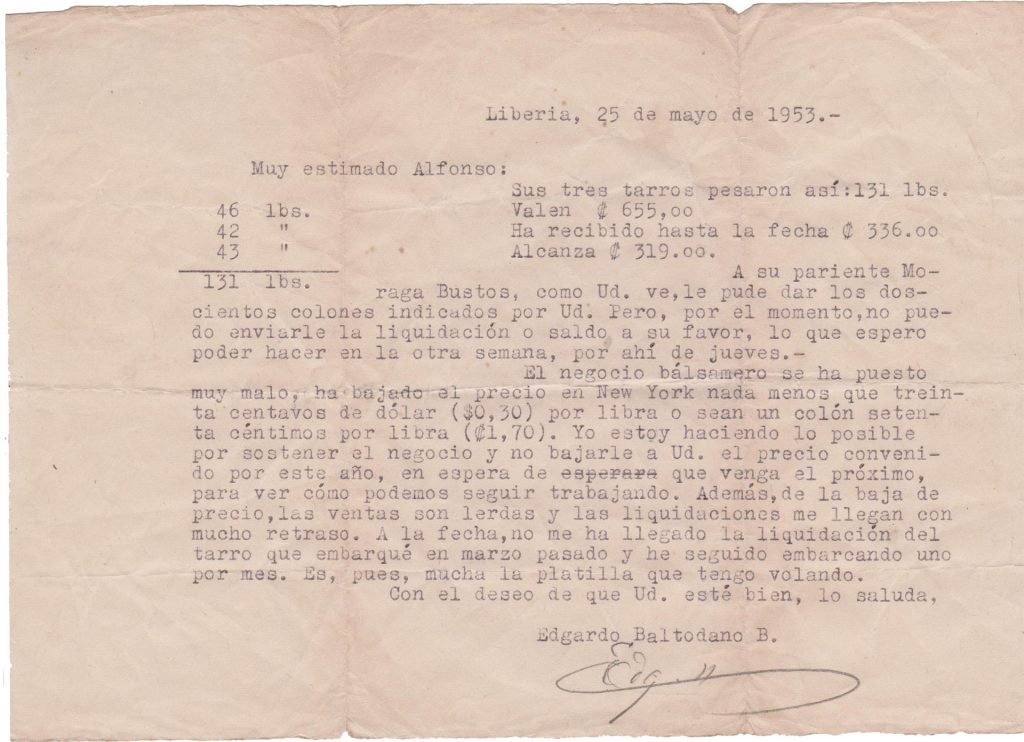

“At one time, we sold the product to the beloved teacher from Liberia, Edgardo Baltodano Briceño. We sent it to him by cart to Liberia and he exported it to New York,” reported Alfonso, who started working at 16 and finished at 27 because the exportation came to an end. Baltodano was part of a well-known family in Liberia. The canton’s stadium bears his name and the hospital is named after his brother, doctor and former legislator Enrique Baltodano Briceño.

Everything was going well, until 1953, when Edgardo Baltodano explained in a letter to Alfonso that “the balsam business has gotten very bad” and asked him for a little more time to pay for the last barrels he sent to New York. That was the first sign that the tree might begin to fizzle out.

Now, balsam harvesting is an extinct trade, at least in Guanacaste. There are still people who make a living from the balsam trees in the mountain ranges of El Salvador.

In Nicaragua, the families that inherited the tradition from that Salvadoran family are fighting so that the trade doesn’t disappear completely, and also so the few balsam trees that remain in their dry forest are conserved.

Now something similar is beginning to happen on this side of the San Juan River.

What Isn’t Planted Doesn’t Exist

For decades, balsam trees seem to have become a secret of the forest. Sometimes their seeds are seen, but rarely does anyone get to see a tree.

That’s how forest engineer Quirico Jimenez puts it, who has written several books about the trees of Costa Rica.

I’ve walked this country’s forest for 40 years and, well, right now I couldn’t take [you] to any [balsam] tree that I can remember,” he said.

In 1997, Jimenez included the balsam tree of Peru in his book Árboles maderables en peligro de extinción en Costa Rica (Timber Trees in Danger of Extinction in Costa Rica).

Based on that publication, the Figueres Olsen administration issued decree 25700-minae, which prohibits cutting down balsam and another 18 species of threatened trees.

Balsam trees are more likely to be found in protected areas, such as national parks, biological reserves, protected zones or forest reserves, the engineer explained, adding that they can even be found in other parts of the Central and South Pacific.

One of the reasons why the tree is now in danger of extinction is because it was exploited for its wood for a long time.

“The wood of this species is hard. It’s heavy, aromatic wood. When using it, it has very nice finishes. It has been used for making floors, musical instruments, for example guitar and marimbas,” added Jimenez.

Although it’s so difficult to see, it is a species that they continue to research. Just five years ago, Jimenez said, they conducted a study in which they determined that there is another species of balsam (Myroxylon peruiferum) in the country that was confused with the balsam of Peru for a long time.

Alfonso Bustos poses for a photograph with his father in the 1950s.

Because the population of both species has declined, there are people who have taken the initiative to rescue them. One of them is Felix Diaz, a Salvadoran who is passionate about forests, trees and seeds.

Forty years ago in Castelmare in Cutris of San Carlos, Diaz started a tropical forest restoration project with native species: trees, medicinal and edible plants.

The proposal to restore the forest goes against global warming and the food sovereignty of us human beings. We have donated seeds to 56 groups of farmers nationwide,” said Diaz.

Some years ago, he traveled to his homeland just to bring back balsam seeds. He came back with five. Only two of them germinated because the rest were eaten by deer.

“My motto is that we have to recover the native species of Costa Rica and Central America,” he said enthusiastically, adding, “my grandfather, who died at the age of 104, used to say: ‘What isn’t planted is what doesn’t exist. The earth has power to feed all the seeds one plants.’”

This article came from “Memorias del Balsamito” (Memories of a Young Balsam Harvester), a text written by Alfonso Bustos with the collaboration of Javier Baltodano. Alfonso is now 93 years old and lives in Buenos Aires, Dos Rios de Upala. We tried to talk with him, but it wasn’t possible to do so by phone or virtually.

Comments