At 74, Guanacaste farmer Enrique Gutiérrez’s age doesn’t hinder him from leaving the house each morning at 6 a.m. to tend his fields of native maize, known in Spanish as maíz criollo.His purpose in life is working the land near his home in Santa Bárbara, some five kilometers from the center of Santa Cruz.

In his rough hands, which are coated with insecticide because he hasn’t yet obtained organic certification for his crops, he holds small grains of white corn, a native species that Gutiérrez inherited from his grandparents.

There, between his fingers, are the key pieces of the millennial roots of Central America, a traditional crop that dates back thousands of years. Since its initial domestication, the uses of native maize have diversified, from steaming tortillas to chicha colorada, a purple colored drink that can only be made from native maize. (According to local farmers, there is no such thing as genetically modified purple corn.)

Discussions of native maize inevitably turn to genetically modified corn, anathema to these farmers, who long ago decided to fight to protect the traditional purity of their maize. For them, the battle isn’t just about preserving the past – it’s about retaining the ability to produce these crops in the future.

“I keep the seed to be able to plant it again,” says Pedro Rosales, who owns the land where Enrique works. “When it’s dry, I cut and store the best ears to be able to share the seeds with my colleagues. On the other hand, genetically modified corn is made so that you can’t plant it again, because it won’t grow.”

Agronomist Adrián Arias agrees. GMO seeds are patented, he says, and if they are crossed with those from another field, the owner of the patent can demand the contaminated crops not be sold.

Several municipal councils across the country have declared themselves free from GMO crops. Nicoya, Nandayure, Santa Cruz, Abangares, Hojancha and Liberia are part of the 92 percent of (percent? or 92 cantons?) Costa Rican cantons that have banned GMOs, although the legality of these bans is still being debated.

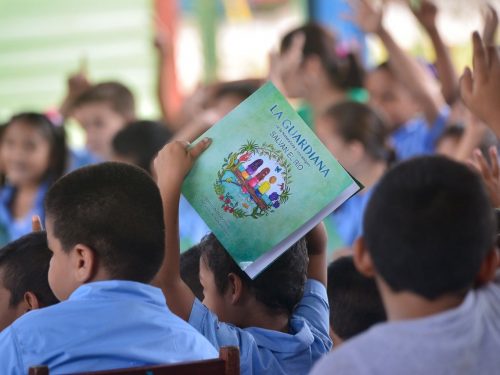

Meanwhile, these children of maize use their hands, their skin, and even their lives to protect the legacy of this rich history, which for now carries with it the aroma of a warm, hand-flattened tortilla. “Our seed is alive.” says Rosales:

Comments