From the top of the Cerro de Las Cruces hill, we can see Nicoya from one side to the other. According to one legend, a large feathered serpent sleeps under the ground. During festivals down in town, we still drink beverages made from corn that we keep in clay containers called nimbueras. Although our language died a long time ago, some words have held out in the names of neighboring towns. Girls are christened with the names of Chorotega princesses and, once a year, a clay ocarina (a wind instrument) whistles across all of Nicoya.

These vestiges of our indigenous culture remain with us to this day and refuse to disappear. It’s what we have left of the small group of Chorotegas that survived plundering, enslavement and massacre.

What happened beginning in the 1520s that made our ancestors start to disappear? The Voice spoke with Elizeth Payne, professor at the School of History and a researcher at the Center for Historical Research in Central America, to understand it better.

The Slave Route

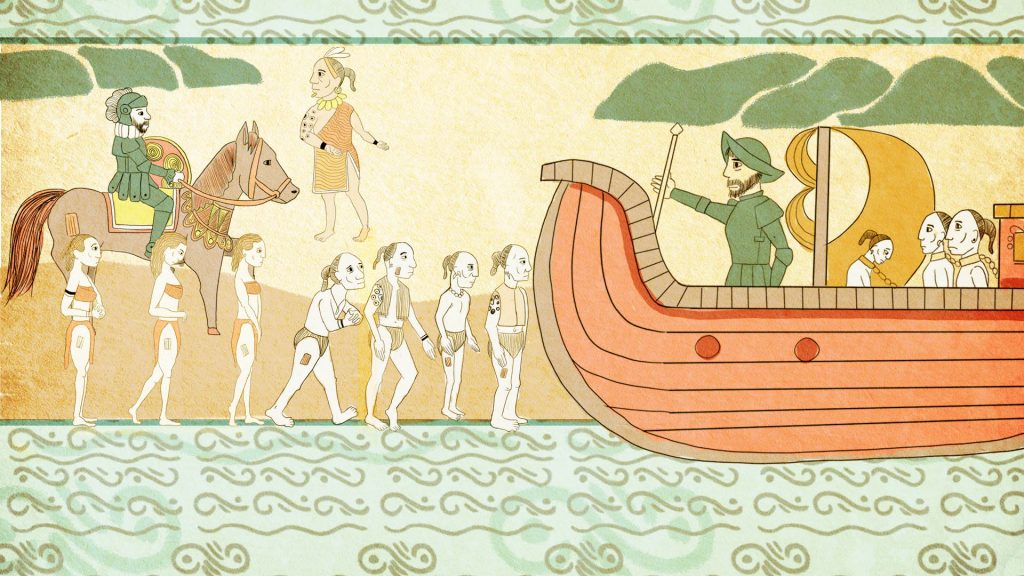

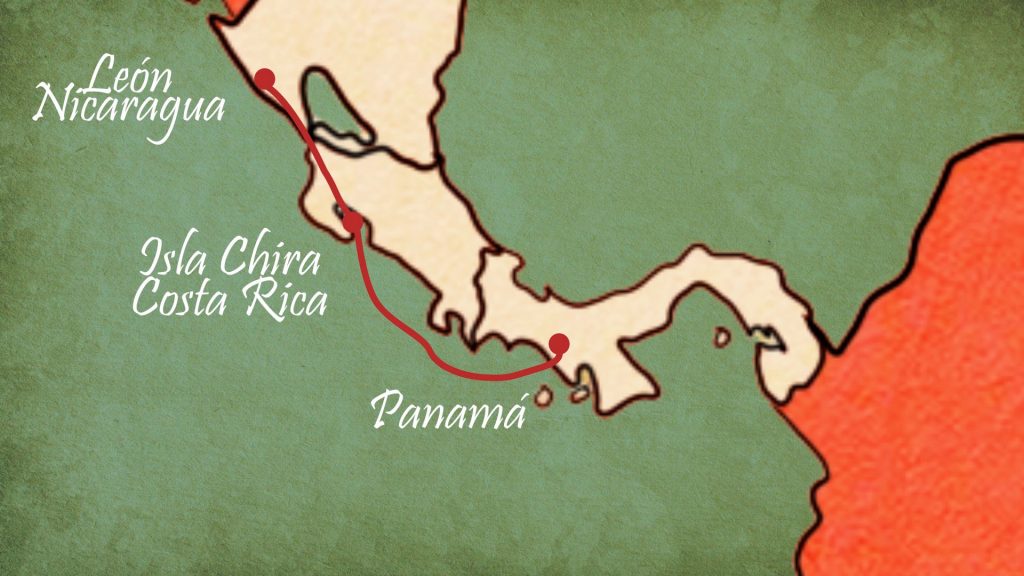

Upon reaching the Gulf of Nicoya, the Spanish found societies with a highly developed economy that included intensive grain agriculture, raising some domestic animals and participating in domestic trade, not just on the mainland but also on the islands. Chira was the most important island because it had the main port in the area. The conquerors took enslaved natives there, sold them, and sent them on ships to Panama and Peru.

Before continuing with this chapter, we need to understand how the Chorotega people were enslaved.

During the conquest, the Spanish read a document to the natives called the Requerimiento (Requirement), which established that they would declare war on them if they didn’t submit to their “new master,” the King of Spain.

Many peoples, including those of Cacique Nicoya, probably accepted it as a policy of non-aggression. Documents from that time explain that Nicoa supplied the Spanish with food, cloth and also slaves. From that moment on, the Spanish obtained indigenous people in several ways.

Credit: Dunkan Harley

The first ones that they had under their control were natives enslaved by other natives. Even before colonization, the caciques (chiefs) had prisoners that they captured from enemies and enslaved. They handed them over to the Spanish, but when they didn’t have any more left, they were forced to hand over indigenous people from their own peoples, especially the most humble and poor, known as “macehuales.”

The enslaved indigenous population declined due to overexploitation, illnesses and famine. When that happened, the Spanish began to sell their natives under the encomienda labor system.

These natives weren’t slaves, but the Spanish forced them to provide services in exchange for converting them to Christianity, educating them and governing them.

The colonizers justified the encomienda system by arguing that “due to their mental deficiency, the Indians were incapable of living in the manner of the Spanish.” When they were finally sold to others, then they did become slaves.

The historian described this period as a time of absolute plunder without mercy, due to the cruelty with which the owners marked their slaves. They branded each one of them with a hot iron and put their mark on them.

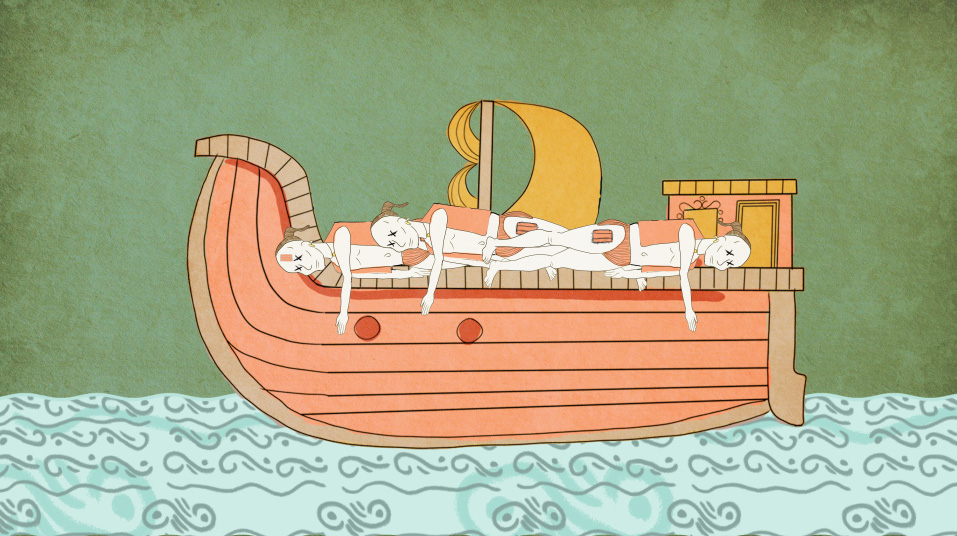

“The men and women were branded before they were sold. They burned the skin on their faces and legs. They marked them forever. Some died on the ships from burns or infections,” the historian related.

The Great Plunder

The Spanish brought many of those enslaved from Nicaragua by land since the winds from Culebra Bay made it difficult to make the journey by sea. Some belonged to indigenous groups other than the Chorotegas.

They continued their journey from Nicoya to Chira Island and from there, they set sail for Panama, where some were sold and others were sent to Callao, the port of Lima, in Peru.

Credit: Dunkan Harley

In Panama, they were bought by silver merchants or Spanish officials who used them as laborers and porters during the time of silver extraction in Panama. Those who were shipped to Peru worked as construction laborers building the city of Lima.

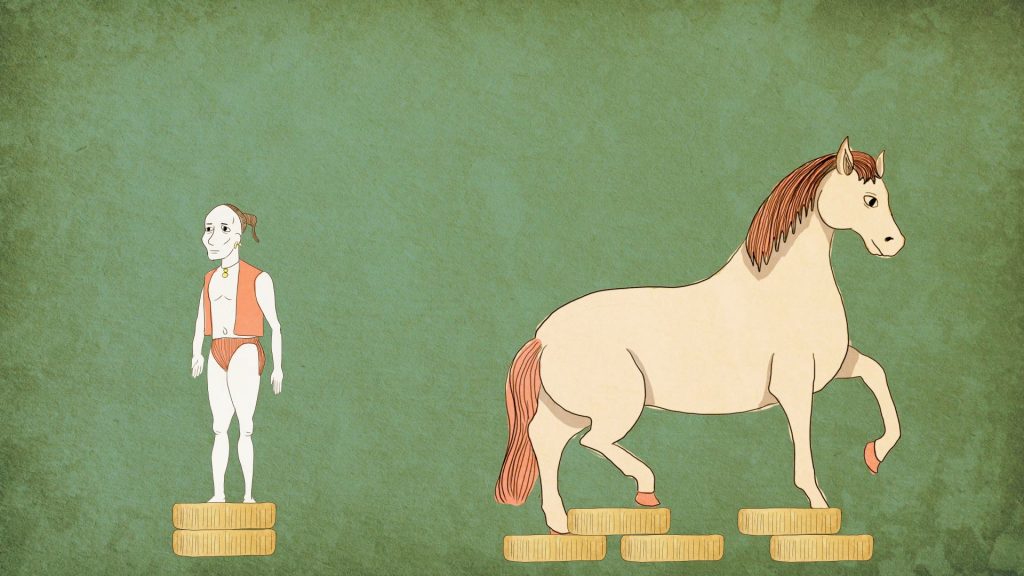

The price of native slaves varied greatly during these decades. When colonization began, an indigenous person cost one or two pesos, but the price went up to 100 or 200 pesos when they became scarce due to the repression. Despite this, a slave’s value was much less than that of a horse, which could cost between 500 and 800 pesos.

The Spanish chose Panama to transport their entire trans-isthmus economy because it’s the narrowest part of the Central American isthmus. The silver that came from Peru reached Panama City, transported by mule and also by indigenous porters to Nombre de Dios, 100 kilometers away.

The book The Indigenous People of Nicoya under Spanish Rule, by historian Luis Fernando Sibaja, documents that in the 1530s, slavery was emerging as the basic activity of Nicaragua, which also included Nicoya.

It wasn’t until the end of the 1540s that the slave trade came to an end, both due to the brutal annihilation of the indigenous population and the decrease in demand in Peru and Panama.

Credit: Dunkan Harley

There’s no consensus on how many indigenous people were sent by boat to these lands in the 1520s. Some historians estimate that about 150 indigenous people were taken on each trip while others talk about 10 to 20 indigenous people.

In a matter of 20 years, the Spanish may have transported between 200,000 and 500,000 slaves from Nicoya and Nicaragua to other countries, according to these hypotheses on average.

The Beginning of the “End”

“It was a time of plundering an enslaved population”, Payne stated. She explained that the trafficking was very brief, a decade or two, because it wasn’t sustainable to trade people who died at a faster rate than they could reproduce.

The same book by Sibaja indicates that in 1529, just 10 years after theSpaniards’ first incursion in the Gulf of Nicoya, the indigenous population was reduced by 82%. They were the first to be sold because they lived near Chira Island, the main port through which they were routed to Panama and Peru. They also died from famines and diseases that devastated the populations and at the hands of economic and political power networks, like that of Pedro Arias “Pedrarias” Dávila and his descendants.

Dávila was the governor of Nicaragua, a very powerful figure who created a dynasty with his wife, children and grandchildren. He took charge of distributing indigenous people to his close friends and relatives.

At that stage, the Spanish crown had not yet created regulations to defend the indigenous peoples. This didn’t happen until 1542, when they created the New Laws and set up a legal body to do away with enslavement, the encomienda system and other forms of mistreatment.

The establishment of these laws didn’t mean a peaceful transition. In the 1550s, Bishop Valdivieso arrived in Nicaragua, appointed as protector of the indigenous people. He was in charge of abolishing the encomienda system in Nicaragua and making sure the New Laws were followed. However, the Contreras, grandsons of Pedrarias Dávida, rebelled against the Spanish crown and violently murdered the bishop right in the cathedral itself.

The Spanish continued to use legal loopholes to take advantage of free indigenous labor and to hold on to their slaves and their power.

Just as there are remains of the Chorotega culture in our towns, there is also evidence that the colonialism of 500 years ago remains alive. There’s a reason why we keep naming our schools after the conquistadors.

Comments