It doesn’t matter where they walk, the stares no longer follow them. They aren’t strangers anymore.

This is the story of Mathew Oyumare and Mohamed, who just over two years ago crossed six countries to reach Costa Rica and who now dream of one day living in Canada, finding a formal job and having as little memory as possible of the journey that brought them here.

They don’t share the same bloodline, but their stories are very similar. They didn’t travel together, but along the way the lived through the same struggles.

In April 2016, amid an immigration crisis, Costa Rican President Luis Guillermo Solis thanked the town of La Cruz. Without this “noble town,” he said, the work of the authorities to take care of the immigrants who were stuck there for months wouldn’t have been possible.

Two years later, in 2018, La Cruz still embraces that discourse.

From Nigeria

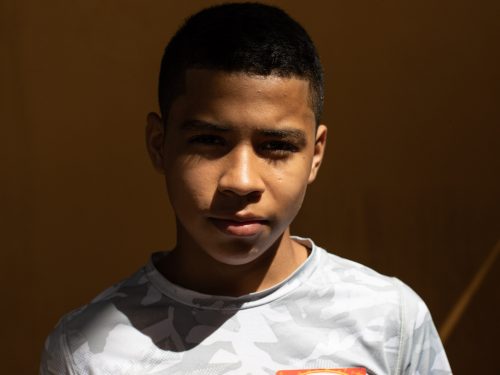

Mathew was almost 27 years old when he left his country, Nigeria. He did it alone, without family or friends.

He was a businessman who decided to “see the world,” he tells us. He wanted to see what else was out there for him.

Like many Haitians and Africans who migrate to the Americas, Mathew says that Brazil was his entry point, a destination well known for its vast border. From there, he started to travel north, crossing through Peru, Ecuador, Colombia and Panama, until he reached Costa Rica.

“It wasn’t an easy journey,” he tells us, recalling what he lived through in what is considered Latin America’s most dangerous and intransitable region: The Darien Gap.

Oyumare didn’t want to go into detail. He made it clear to us that he wouldn’t talk about that.

In the words of BBC Mundo’s journalist Alejandro Millan, the zone is “hell, like an impregnable, impassable, dense jungle.”

The Darien Gap is located on the border of Panama and Colombia and has served as a natural barrier preventing the construction of a highway that would connect both continents. The Panamerican Highway doesn’t cross its 108 kilometers of jungle. It’s what Oyumare crossed to enter our country.

In Guanacaste

What Mathew does talk about is his stay in La Cruz. He entered Costa Rica as part of the wave of African migrants that saturated the country’s borders.

According to Costa Rican Immigration, between April and July 2016 some 4,700 African and Haitian immigrants knocked on the doors of the national immigration office.

Of that total, between 700 and 800 immigrants were located in the attention centers (CATEM) in Peñas Blancas and El Jobo, in La Cruz.

Mathew never used those shelters. The three kilometers that separate the shelter from La Cruz kept him close to where he could make money, which was vital for his plans.

“I wanted to do something because I needed to start working on my residency paperwork. I want to leave Costa Rica with my papers in order,” he told us.

It seems to have been effective. The Super Compro supermarket allowed him to help bag groceries, an activity he performs while he dances and greets customers.

In exchange, La Cruz residents give him the spare change they have on hand.

With this change, Mathew was able to pay for his first night at the La Casa del Viento hostal. He was well received there. Otto Rojas, owner of the establishment, even opened the doors to his kitchen.

“He isn’t like other immigrants that are usually seen walking around the streets of the canton. He is special. He doesn’t cause problems and he is very polite, and even speaks several languages,” he told us, as though he was speaking of a close friend.

He told us that everyone in La Cruz knows and loves Mathew.

“Although it may be all in 100 colon coins, he pays me,” he added. “He is so helpful that no one here has a complaint. He is so good he sends money to his sister in Europe.”

One More Story

Mohamed is 30 years old and he comes from a country further west in Africa called Ghana.

Much like Mathew, the path to Costa Rica started in Brazil and from there he went north.

But remembering the journey seems to cause him deeper pain than Mathew. Or at least that’s what we felt.

“Only God knows what protected me in order to get me here. You see many people die along the way,” he said as his eyes watered with tears.

He didn’t want photos taken, but he also didn’t want to be rude, so he spoke with us about his experience in Guanacaste and about leaving his country as an accounting student.

He also said his residency is in process and that he hopes it is resolved by September.

While that is in the works, Mohammed earns a living helping out at the Musmanni bakery in downtown La Cruz. They let him make tips by packing bread for customers.

It only took us 20 minutes outside the locale to see how the people of La Cruz already know what his tasks are and how they expect to be attended to by the Ghanaian, who, two years ago, was a total stranger.

Why Judge?

Neither Mathew nor Mohamed plan to stay in Guanacaste or Costa Rica to live for the rest of their lives. And it’s not because they think that our country isn’t enough for them. To the contrary. Their affection for the people of La Cruz seems deep.

“This is a great country. I don’t want people to think the wrong thing,” Mohammed says. “But if we have Canada in mind it’s because we believe that we can do better there. I speak English well and there are opportunities there.”

Mathew agrees. “Guanacaste has treated me very well, people have treated me as if I were a part of their family.”

La Cruz, for its part, seems to be a town deserving of the praise.

Gregorio Ortiz, a 70-year-old native of La Cruz, says he is used to “people from other countries” coming and going, but that in the case of “the dark-skinned ones” something peculiar happened. “You know who they are.”

According to Ortiz, that’s how the the majority of the town of La Cruz thinks and, according to his perception, this border canton doesn’t bother visitors. Rather, it understands them.

“They abandoned their country. I don’t know what that’s like, and I don’t know if, someday, a friend of mine will have to go through that. I think that we all have the right to live, and live well,” Gregorio says, sitting on a bench in La Cruz’s central park, as a group of five immigrants walks in front of us.

Comments