The school years has started in Los Angeles, Nicoya. At 7 a.m., boys and girls pass through the doors where the facade reads “Proudly Guanacastecan.” Ahead, a mural that says “Welcome” greets them and under the letters are three children with identical features.

The hallways and classrooms are decorated mostly with white kids with large green eyes and, often, blond hair. Very few are dark-skinned like those who actually traverse the halls of the school.

The Voice of Guanacaste visited this school and others to see what the walls say about who Guanacastecans are.

Beyond July 25

Schools don’t tackle the racial backgrounds of Guanacastecan boys and girls with daily and modern examples. They use historical memory, says Institute of Studies for Central American Development sociology professor Gabriel Vargas.

“It’s an exocit, folkloric role that, in a way, we mythologize,” Vargas explains, since diversity seems to be celebrated only on certain dates like Culture Day or the Annexation of Nicaragua.

At the Guanacaste Institute in Liberia, for example, indigenous features are represented with images on the walls of men in feathered caps in the middle of corn fields or with exceptional cases like Guatemalan indigenous leader Rigoberta Menchú.

Andrea Vindas shows one of the murals she makes for schools or professors. One of them asked her to incorporate different ethnicities in this work, but that doesn’t always happen.Photo: César Arroyo

“Beauty has stereotypes and pretty girls can’t have dark skin, unless it’s for Reinado del maíz (a cultural pageant),” says Irina Umaña, professor of plastic arts a the Los Angeles school in Nicoya. She has used her lessons to question those beauty concepts with her students and urged them to stop using the word “black” as an insult.

For her, all the drawings her students make of themselves have to respect skin color. The “pig pink” pencil, as she calls it, is prohibited for her dark-skinned students.

Andrea Vindas shows the palette of tones that she uses to paint skin color. She says that all the designs she downloads from the Internet to make the figures come in white skin. After the interview with The Voice, she assured that from now on she will try to make at least half of drawings in brown skin.Photo: César Arroyo

Forget about the Switzerland of Central America

For Vargas, the first step towards accepting this ethnic richness that all Guanacastecans carry is recognizing that there is a problem, and that we created the myth of the Switzerland of Central America, which has made us think that we are whiter than neighboring countries, and a source of pride.

According to sociologists, our country was founded on the belief that Costa Ricans are white, like the coffee pickers on the five colon bill. We unconsciously hold on to this belief today.Photo: César Arroyo

“In Costa Rica and Latin culture, we often practice ‘colorism,’ meaning that the darker you are, the uglier you are. At school, those values are reproduced,” the sociologist says.

Changing those deeply rooted ideas isn’t easy. That’s why Irina has other tactics so her students value themselves and love themselves how they are. “I’m convinced that when I take a girl to the mirror and I tell her, ‘did you know that you are beautiful,’ and she blushes and tells me ‘no one has ever told me that,’ I know that something changed.”

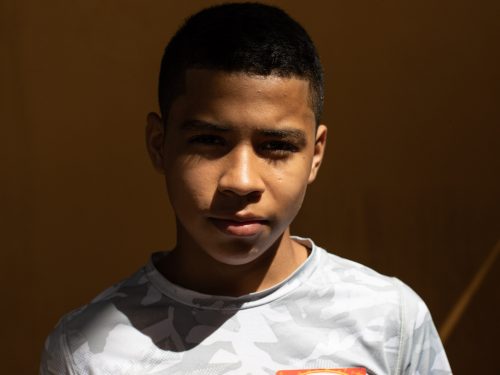

Fifth-grader Brayan Alfaro Zumbado paints his self portrait during plastic arts class at the Los Angeles school in Nicoya.Photo: César Arroyo

Comments