Every time Ana Iveth Guzmán goes out to the mountain to make a call, she puts on some boots, grabs a machete and walks around 15 minutes along a trail to find a cellphone signal. In San Vicente de Santa Cecilia, in Northern Costa Rica, mountain is a word for everyday use. It is what surrounds a handful of houses in this cross-border community of La Cruz de Guanacaste. The mountain is the banana plantation, the workplace, the overgrown grass, the place where the baseball matches are held, the mud, the mahogany, the trails…

That is why, on December 19, 2018, when one of Iveth’s sisters-in-law walked towards El Tablón (Nicaragua) through one of those mountain trails, nobody worried that she was going there alone. Because the mountain was, let’s say, the life of San Vicente.

Life in San Vicente

It smells like wet soil. The air of San Vicente can be squeezed out with one hand as if it were cotton. Christian Osegueda and his dad, Freddy, descend down a road made of loose stones in their pick-up, which has a wooden cargo bed. Although it feels like a risky journey, four years ago they couldn’t go down by car, only by horse or on foot. The road only came after a misfortune. Freddy uses a metaphor to describe it: When hurricane Otto passed, it grabbed the whole mountain and threw it into the river.

The Oseguedas are merchants and intermediaries. This time, they bring diesel from the center of Santa Cecilia. Other times, they bring oil or food that they exchange with other families for the green plantain they harvest.

The farmer Misael Villagra looked for Darys Mora for hours on December 19, 2018. Misael assures that everyone in town knows who killed her and says that the murderer even participated in the search. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

People cannot buy their daily groceries in the center anymore: authority control has increased in times of Coronavirus, and their motorcycles would be taken away, or they could even be deported because many of them do not have Costa Rican documents. In the middle of a pandemic, they cannot go to Nicaragua either, to El Tablón, which is about 20 minutes away and where products are cheaper than on the Costa Rican side. They would not be able to re-enter because now that border has police surveillance.

It is 9:37 am on Friday, July 3. The pick up parks in front of Ólger Zúñiga’s house, who comes out to say hello, although today he’s not selling. In pre-Covid times, Christian and Freddy would buy a thousand plantains per batch from each family, but now…

“Now it’s 200 from you, 200 from you, 200 from you, so that they all sell something because it would break our hearts to buy only from one family, and have the rest watch the loaded car driving away”, says Christian, who always smiles when he speaks and, while studying hydrological engineering at the Costa Rican National University, helps his father sell from house to house.

Today, they are taking 500 plantains in total and will see how it goes, because the hotels, their biggest buyers, don’t even have guests, and the canton remains on orange alert.

Ólger has brown skin and beard stubble. He arrived from Birmania de Upala, in the province of Alajuela, 26 years ago. There was no one, people had left because of “the savage war against the Sandinistas”, (the Nicaraguan civil war, which lasted until 1990), but “afterward they returned to their properties,” he says.

San Vicente is a town of migrants, many of them irregular. Thus, it was populated little by little, as tends to happen with bordering areas without much attention from anyone. It is a remote town that can only be reached by double wheel drive or on horseback, in one of the poorest districts of Costa Rica: Santa Cecilia, in the canton of La Cruz, which also ranks second to last in the Social Progress Index of Costa Rica.

Badly woven between the border forrest, San Vicente was forgotten by the State, by the media, and by the police… until the Coronavirus pandemic arrived. The police were never more present than now. Not even when Darys was killed.

The big “move”

In 1999, another family arrived in San Vicente from Nicaragua, like many people who decide to move to Costa Rica (around 376,000 Nicaraguans live in the country, according to the 2019 National Household Survey). They were searching for a life almost equally as poor, but with more work. Leda Gutiérrez, her eight-year-old daughter Darys, and her other five children, got on the bus in the municipality of Nandaime, in Granada, Nicaragua, and then crossed by foot through some of the trails that lead to San Vicente from the town of El Tablón, in Rivas.

The first two years in Costa Rica were spent with a man who gave them accommodation, in a house on the other side of the river. The shortcomings were many. Her family gathered water in the small wells on the slopes of the Orosí river, which runs hard until it reaches Lake Nicaragua. Then, they moved to San Vicente to look after a neighbor’s land.

Coming to Costa Rica did not give them a life of abundance, but at least the rains were stronger for planting, says Leda, who welcomes us to her home, on a hill of red soil. To get here, you have to cross the river or go around the town of La Virgen, to then cross a hammock bridge, and walk 20 minutes uphill.

Their house is comprised of two huts made out of wood and zinc with a latrine. There is a soccer goal without a net through which you can see Lake Nicaragua and Ometepe Island. An exquisite 5-star hotel view, in the middle of extenuating poverty.

In the property, you can find laying hens, tiny cats, and some ducks. The family grows corn and vegetables that nobody buys from them, but that is enough to at least feed the 10 people who live in the house, including children, grandchildren and adults.

Leda stands uncomfortably in front of the cameras, leaning back on a clay oven. Although drinking water has been available in the area for about three years, electricity still does not reach the school. A handful of aqua green classrooms remain motionless, without children, 400 meters below. To charge their cell phones, they go to a neighbor’s house and pay 300 colones for it.

A grieving family

Darys’ mother is a talkative, smiling woman. While the children look at us expectantly, Leda tells us that Darys was well behaved since she was little. She never messed with anyone and she liked to share food. “If someone passed by, she would give them food, she would get something ready for them,” one of her friends recalls. “There was no daughter like her”, says Leda, with a broken voice. “I do not even wish to remember it. It’s too painful,” she explains.

Leda Gutiérrez, Darys’ mother, lives on a hill where electricity is not available. In this clay oven she baked sweet donuts and biscuits, but it was damaged by the rain. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

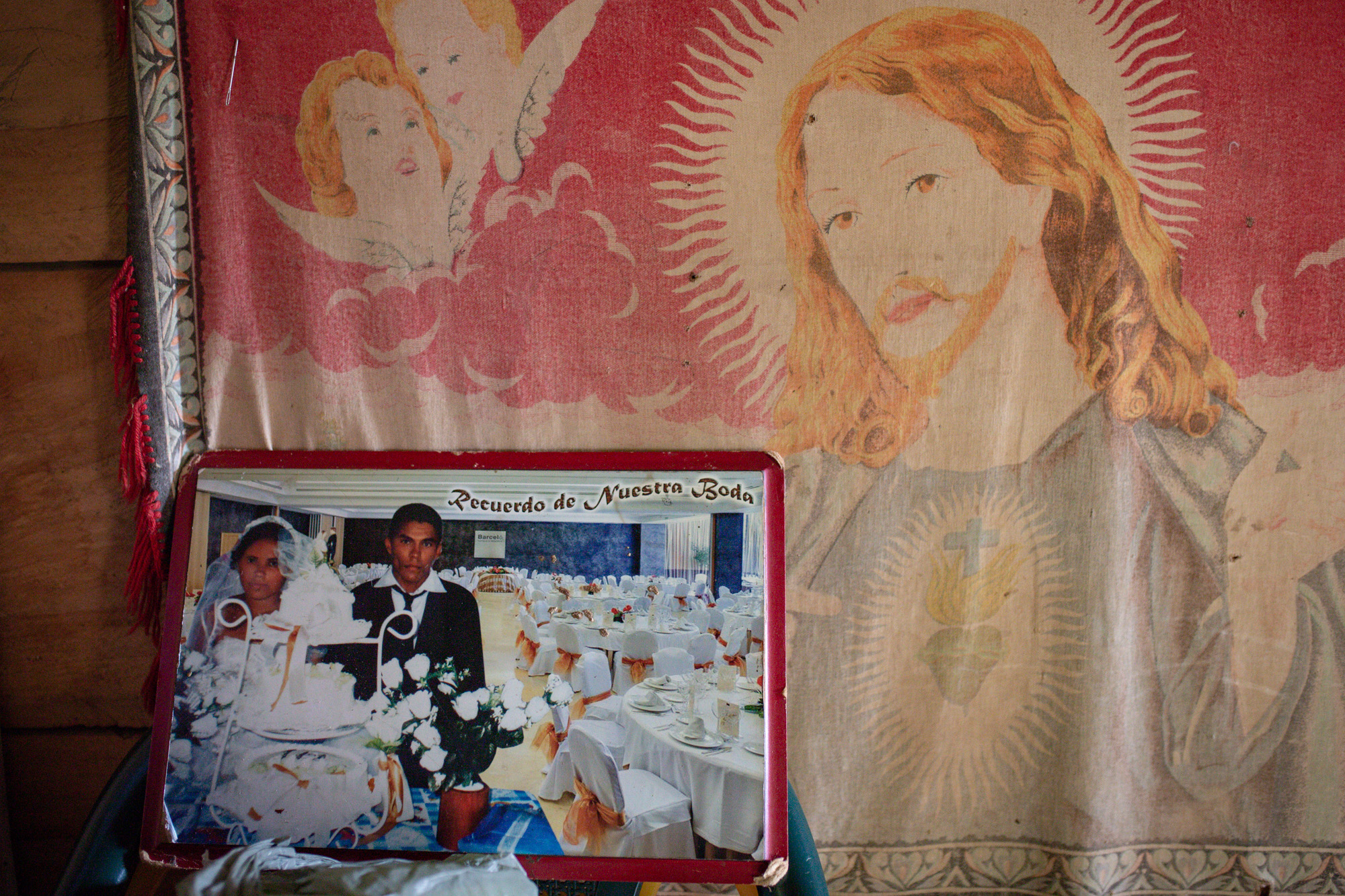

Darys finished primary but not secondary school. At 15, she started dating Eliézer José Chávez, a farmer from the same town. They married three years later. Eliézer’s parents realized she was pregnant and told her not to rush the wedding and get married a few months afterward.

“Leave the marriage for December, maybe there will be a little money,” Eliézer’s mother told him. But Darys didn’t want to, so he asked for her hand right away. “I did what I could,” he recalls. The wedding was in the Asamblea de Dios (a Pentecostal church), where Darys later organized Christmas gifts exchanges for children.

Darys and Eliézer had two children: Olman and Jolvin, who are now nine and seven years old. They looked at us, confused and curious, from the steps of one of the huts, hanging from their father’s neck.

Olman, the oldest, has light eyes and a frown, as if angry. After his mom was murdered, he got sick. “He had pain in the pit of his stomach”, says Eliézer, who scratches his hands, which are stained from the poison he uses for corn, and remains static, silent, smiling only for a photograph embracing the boys.

The family is worried about Olman. They say he is depressed. A few days after our visit, his aunt wrote to us asking if we could help her look for psychological attention or some sort of emotional help for the child.

The youngest is the one that looks most like his mom, says grandma Leda, who is only 50 years old and is the grandmother of nine children. But these two, Darys’ children, are the apples of her eyes. “The youngest one is the most playful,” she says fondly. He can’t see his grandma doing something because “there he goes: ‘Can I do it for you, grandma?’” Just like Darys.

To prove how much they look like her, Leda shows four photos from a cell phone with a broken screen protector.

In one of the images, a girl with a round face and kind eyes smiles from a rocking chair, on a dirt floor. In the other three photos, the same woman is submerged with her clothes on, with the help of a man, in the water of a calm river. Darys was baptized two years before the femicide.

Disappearance from town

“It was on a Wednesday that she went to El Tablón. She left at six in the morning. We were going to have tea at the church, so she left in the morning to go get the present, to buy it there, in El Tablón. I was going to go with her that day, but since she was very fast and she liked doing everything in the morning, I didn’t go”.

Darys’ in-laws, Vilma and Juan Benito, keep a photo of when she married Eliezer. Photo: César Arroyo Castro

Iveth Gutiérrez is a friend of Darys and the president of the association of farmers and ranchers of San Vicente and Pueblo Nuevo. She is a tireless leader who sends handwritten letters asking for help for her town, demanding attention and dealing with the frustration that injustices bring to her community.

We visited the home of her mother-in-law, Vilma García, and her father-in-law, Juan Benito Chávez, who were also Darys’s in-laws. Vilma is a big woman with a dark complexion, her eyes lowered under several layers of skin. She sat next to Iveth on a platform that supports the house made of wood and dirt. There were green plant pots outside, and a rooster that wouldn’t shut up. They told us what happened on December 19, 2018.

Iveth: “(Darys) left and dropped the little ones off with her (with Vilma) because she lived upstairs. She said she wouldn’t take long, but that she’d leave the kids there and asked to send them back to her when their dad arrived”.

Vilma: “She came by to drop them off. We were in the paddock. The mistake was that she told me she wouldn’t come to pick them up. That was the mistake”.

Vilma blames that moment for all the subsequent tragedy. If only she had been waiting for Darys to walk by, maybe she would have told Eliézer to go looking for her with the workers earlier. “Then they would have run into those murderers,” she regrets.

Since she didn’t see her go up (the mountain) again, she worried for a moment but then figured that it was normal. Because, of course, she must have gone directly to the church. “Since she’s fast…”, she thought to herself.

That afternoon, when the boys became restless, Vilma took them back to their house.

Vilma continues: “The first thing that I found: the breakfast dishes. ‘Man! Darys didn’t wash the dishes, I know she keeps the house clean.’ I waited for her until four in the afternoon, but she never came”.

“My son was sitting over there. ‘And Darys? Did you find her?’ He didn’t even answer me. I began doing their dishes, I swept, started grinding, and started the fire. ‘I’ll leave you these tortillas,’ I told him. ‘I’ll come tomorrow, God willing. Tell her we’ll do what we talked about tomorrow’”.

“I went home. He arrived at around six-thirty. I was inside and he said ‘Mom’, ‘what?’, I asked. ‘Come here’ (…) I thought ‘what could have happened?’. ‘Did you fight with Darys?’ I asked. He told me: ‘Darys has not arrived from El Tablón’. ‘What?!’ I said. ‘Where are you going?’ I said. ‘I’m going to look for her, I’m going with her dad and her brothers’. I was screaming. And he says to me: ‘Go back to the house. Some women stayed there.’ I couldn’t walk from the nerves”.

This story may interest you: What Must We Do to Combat Xenophobia Against Nicaraguans in Costa Rica?

Iveth: “When she (Vilma) arrived, I called the police to see what they could help us with. They told us they would come, and after a while, at around nine or nine-thirty, a patrol car came and I told them that a girl got lost and that we needed them to please at least come with us to look for her on the edge of the border. They told us they couldn’t come along because, aside from the fact that there were only two of them, they had to wait 48 hours to start looking for her”.

“They were outside of their car and took notes and everything. But well, nothing. Then I said ‘Maybe they’ll come in the morning’. They didn’t come. They left and just told me to go report it to the OIJ”.

Commander Rodrigo Alfaro, regional director of the Public Force on the northern border, later told us, by phone, that he reviewed the police file on the date Darys disappeared and concluded that the two officers acted according to protocol.

“She had crossed to Nicaragua. So what officials recommend is, first, to give it a bit more time, and second, to wait to file the missing person report at the Judicial Investigation Body (OIJ)”.

According to the chief of police, the waiting time to act in cases of missing adults is 72 hours. “It is not established by me, but by the OIJ,” he said. However, the OIJ, the body in charge of investigating crimes in Costa Rica, has repeatedly stated that there is no minimum time period for reporting. The alert must be given immediately and the officers will assess each situation.

Kathia Rivera, the director of police legal support from the Ministry of Public Security (to which the Public Force belongs to), complements Alfaro’s response by indicating – through the press office – that the investigative competence is exclusive to the OIJ and that the Public Force provides collaboration.

But at that time the OIJ did not consider Darys to be missing, but rather that she had gone to Nicaragua to do some shopping by her own free will. “Unfortunately, she was later found dead, already on Nicaraguan territory,” reads the email that was sent out as a response to inquiries about the case.

And that was it.

It was already December 20 when Darys’ father returned home after the search he did at night, still without results.

Iveth: “It was around 2:40, already in the early morning, and I told him (Darys’s father) that this was not good at all, that we had to go to Liberia to file the report of missing people. At three in the morning, I started my bike trip to Liberia and arrived there by five in the morning. On my way back, I was in La Cruz when my father-in-law called me. He was crying inconsolably, and he said ‘Come, they found her. And she’s dead.”

Vilma García moved to Darys’ house, so that she can be with her grandchildren.

A body wrapped in plantain leaves

“We walked looking for her at around midnight, and at one in the morning”.

Misael Villagra finishes loading the 500 units of green plantain into Freddy and Christian Osgueda’s truck and he drains the water from his boots: the river was high and the horses had to fight against the current, but it is the only way they have for bringing the harvest to this community. He knows what we’re talking about when we ask him about the femicide of a woman that took place two years ago. All the inhabitants of San Vicente remember that night and early morning in December.

Misael says: “The next day we walked all over the area, and we found her. It was about to be 10 (in the morning) when we found the girl there, under a tree trunk.”

“We were about 50 meters away when they said, “She’s here!”. They came, and we saw some kicking and pulling, they looked for a stick and removed some plantain leaves, some rotten stems, and saw where she was cut off”.

“The Nicaraguan police actually came to pick her up, because she was on the other side of the border. The… what are they called? … the forensics arrived. Legal Medicine. They came at around one, or two in the afternoon”.

Iveth arrived before the police: “The forensic doctor checked her there, at the same place where they pulled her out of the hole. The doctor did everything right there, the autopsy. In Nicaragua, things are very different from here. The forensics do everything right where the person dies. So they undressed her there. They looked for helpers, and the one who found her, my brother-in-law, had to dress her again”.

The Nicaraguan Ministry of Health issued the death certificate seven days later. It indicated that the cause of death was “mechanical asphyxia due to manual strangulation”.

Homicide by strangulation occurs when the victim’s neck is squeezed so hard that the carotid arteries stop carrying blood to the brain and the brain runs out of oxygen. Therefore, the person passes out and dies.

That’s all the family was able to find out about Darys’s death. The copy of the document that they have – the original is at the children’s school – is the only official document about the femicide on this side of the border.

Everything else is what they themselves have drawn up in their head. “She must have screamed when they were torturing her”. “If she was half alive, surely she drowned. She could not breathe with the body on top”. “It looked like there was water in the hole”. “Of course, that’s where she drowned”.

The certificate does not mention the word rape, but the family and the neighbors claim that the forensic doctor said that there had been a sexual assault. “That’s what (the record) it says, just that, it doesn’t give more details. But yes, the forensic doctor said that she was raped, strangled and that her neck was broken”, remembers Iveth.

The Law on Criminalization of Violence Against Women defines femicide as “the death of a woman who maintains a relationship of marriage, registered partnership or not, with her perpetrator.”

However, the Convention of Belem do Pará extends the concept to all violent deaths of women due to their gender. They include homicides during a relationship, after a divorce, after the termination of a registered partnership, and those that occur in the public sphere, for example, as a result of a sexual assault. In Costa Rica, the term “expanded femicide” is used for statistical purposes.

When she saw that the forensic doctor was leaving, Iveth asked what they could do to bring her body to the Costa Rican side. She remembers he told her that she had to show proof that she had filed the missing person’s report with the Costa Rican OIJ. With that, he said, they would be able to bring the body to this side of the border, without any diplomatic procedure of authorization from the Ministry of Health, as the law dictates.

And there they told her, “She’s ready now, you can take her”.

Iveth: “Since she had been there a while, she was already very… she was starting to decompose. So they put formalin on her and wrapped her in a blanket, or was it plastic? In a black plastic then. She was put in one of those hammocks and the body was carried with a stick. People brought her on their shoulders. The neighbors, family members, brothers. Those who were fitter.”

On the day we interviewed them, Iveth and Vilma were seated at the same place where Darys’s body was placed. Iveth pointed to a hammock that was hanging above a table. “She was put into one of those hammocks”, they recalled.

“She was placed here, there was a bed here, and we laid her down. I washed her with the help of my sister. We did everything ourselves. The forensic doctor injected her and gave her some things, but we did the rest”.

Iveth remembers that, when they washed and cleaned Darys, they saw that her tongue was bitten, her fists were clenched with dirt in them, and the neck was “broken”, strangled.

“She was unrecognizable. Her lips were turned, from how injured her face was. She had like a cut, a wound here (in the back of the head), with a machete, as if they put a hole in her head. My sister said crying: ‘who did that to you, tell me who did that to you?’”. They said that around 300 people came to see her. The line was about a block long.

Who is the murderer?

For the judicial system in Costa Rica, Darys is invisible. No investigation was initiated for the homicide due to a legal principle called “territoriality”, the Deputy Prosecutor of Liberia, Elvis Lopez, explained by phone.

Territoriality is a legal term that forces the country to apply its law only to acts committed in its territory. “It is a question of sovereignty”, emphasizes the prosecutor. Darys was killed a few meters from that imaginary line that draws the border. She was murdered where it no longer is Costa Rica.

If she had been Costa Rican, this legal principle would have an exception and Costa Rica would be able to assume and have a say in the case, Lopez later explained. “But that is only as long as Nicaragua has not assumed it.”

In Nicaragua, there is an arrest warrant against Luis Adalberto Acosta López, known as El Ñambo, for “murder” and “aggravated rape” against Darys. Everyone in town assures that he was the one who killed Darys, and that it was not the first time he had raped a woman.

The Rivas Prosecutor’s Office presented the accusation on January 14, 2020. Two days later, on January 16, Judge Sandro Pereira issued an arrest warrant.

On that same January 14, a Nicaraguan pro-government media outlet published that the police in Rivas had “clarified” various crimes. The first of them is the crime perpetrated against Darys. The outlet also assured that López had “a long criminal record”, and remains a fugitive. In the town, it is rumored that the Nicaraguan police captured him once and he escaped, but this rumor has not been confirmed.

Despite his status as a fugitive, the International Police (Interpol), which in Costa Rica operates within the OIJ, affirms that neither Costa Rica nor Nicaragua have requested any diligence on this suspect. Interpol facilitates the exchange and access to information on criminals between countries.

The commander of the Public Force, Rodrigo Alfaro, told us the same when we asked him if there was an arrest warrant for El Ñambo, and we told him that neighbors claim to have seen him on this side of the border.

“No, no, no. These types of tips are handled in a formal way,” he told us, to justify that the police will not carry out a search on this side of the border.

Silent Christmas

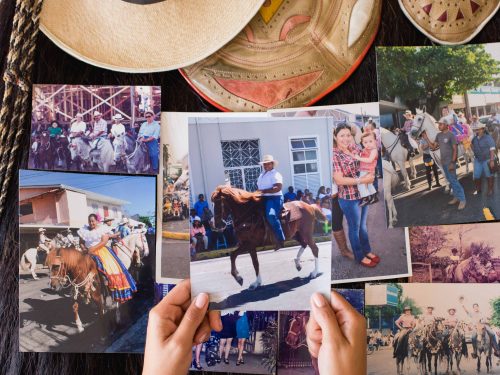

Darys left an entire wall filled with drawings made by her children, handwoven fabrics, a pillow, and a Christmas boot. The town of San Vicente did not celebrate Christmas that year. “There was a terrible atmosphere change here. This little town was mourning for more than a month”, shares Misael Villagra, while he leaned against the pick-up truck that will take the plantains.

The board that Darys made with her children, Jolvin and Olman, days before Christmas. Photo: César Arroyo

Acceptance, for some, comes little by little. “I couldn’t accept that she is dead. Not even in that hole where she was. ‘Maybe she’s alive. I’m going to go talk to her,” says Vilma, Darys’s mother in law. “We are never going to forget that”, says Iveth.

But Darys’ femicide is not just a tragic memory. It is a constant resentment. Lots of open questions. What would have happened if the police had helped them out, or if they themselves had reacted sooner?

“You call the police, you call someone from outside that you think is really going to protect you. Yes, I know it’s not Costa Rica’s turn, but it’s the police doing a little more from their side. You are desperate, and to be told ‘I can’t’, makes you more desperate,” says Iveth with eyes that have turned red, without crying even once. “So, where is the justice? If I do it, it’s wrong, I would go to jail”.

Aside from the doubts, there is also fear. A shock that is stuck in their chests, especially among the women who live in this town. “When the men are not here, I’m scared. I lock myself inside or I’m waiting. That man could come in through my window,” says a friend of Darys, Yendry Gómez.

“Knowing that the one that did this is walking around here, and people see him and they come to tell you ‘Look, be careful, that man is saying he’s coming for more’’, adds Iveth.

“A little while ago they told us that he came to this house to see if we were here. He would come to us, to kill us. I don’t know, I can’t tell you if it’s real or not because I didn’t see it,” says Vilma.

Walking alone through the trails that lead to Nicaragua or the nearest town in Costa Rica has become a risk. “You travel so much here, to get the bus, for an hour, and the road is so empty. Knowing that at any moment I, my sisters, my mom, that it could be any of us again. That man can come out of nowhere, and the authorities know it because it is not the first time he has done this”.

Iveth doesn’t sit still. A while ago, she sent a handwritten letter to the Border Police chief himself, Allan Obando, “to see if they could please patrol this area more”. But they have not responded.

Commander Alfaro, from the La Cruz Public Force, argues that the characteristics of the area would make patrols difficult: “It is a wide area, with forest, vegetations, farms. The roads are bad or in terrible conditions, and in some cases, there are no roads, only trails. This makes it even more difficult to reach, the presence of police in these different locations, at the different villages, many of them established within a farm that can measure a thousand hectares or more”.

Ironically, the neighbors have seen patrols in recent days as part of the border operation to prevent Nicaraguans from entering Costa Rica.

Prosecutor López adds: “It is particularly complex, because of the extraordinary ease with which people can move around and cross to a different country in a matter of minutes.”

“We see ‘coyotaje’ daily, which is migrant trafficking, smuggling. In 2019, there were around 16 homicides in La Cruz, a good portion of those in the sector of the border. They are very open, very rural sectors. This makes the population very reluctant to collaborate and there are almost never witnesses,” adds López. But he assures that if any member of the town wants to report, they can do so without running the risk of being deported and that the most important thing is the investigation.

None of these explanations convince Iveth. “Could it be that you’re not worth anything if you live in a cross border community? she wonders.

Before we leave, she asks for just one favor: to ask at the ICE if they can put a cell tower. That way, women like her won’t have to walk through the mountain to make a call. Now the mountain represents death, and it’s everywhere.

Comments