Tourism has become the bread and butter of Costa Rica, and for many it has taken on a more palatable flavor than a career in agriculture. This has become the case in many coastal towns of Guanacaste like Samara and Nosara, where tourism has been gradually displacing agriculture and transforming the communities. Since 2000, tourism brings more foreign exchange into Costa Rica than bananas, pineapples and coffee exports combined, according to data from the 2006 Tourism Yearbook (Anuario de Turismo 2006). But the shift from agriculture to tourism is not always healthy for the local economy.

Just a few decades ago, the majority in Nosara raised cattle and cultivated rice, corn and beans for local consumption, and a few, like Juan Rafael “Chanel” Mora Madrigal, raised enough to export their agricultural products. Back then, a boat arrived weekly to Garza Beach to drop off merchandise, and from there the items were hauled in a cart to the farther reaches of Playa Pelada and Nosara. That’s what it was like when, about 40 years ago, the first Americans arrived in the area and began to teach English to some locals.

In the 1970s, Samara still had no running water, electricity or bus service. In 1973, a gravel road was opened between Nicoya and Samara, and then bus service between Samara and San Jose began, opening the possibility for more people to visit what was then an agricultural and fishing community.

As the areas became more accessible by road and later when the Friendship Bridge was built in 2003, more and more people, both from San Jose and from foreign lands, discovered the splendor of local beaches like Guiones and Pelada and began to transform the local economy from simple agriculture to a more complex tourism-based variety.

But the difference was that although many towns along the Guanacaste coast have developed mass tourism centered on 4 and 5 star all-inclusive resorts, Nosara and Samara have developed a different kind of tourism, described as “smaller scale, experiential tourism” by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST) report A Portrait of Economic Realities in Nosara and Samara: Providing Tools for Sustainable Development.

“This is high value – rather than high volume – tourism which strives to hire and purchase locally, create authentic links to the local destination and surrounding natural and cultural attractions, and ensure that tourism dollars stay in and benefit the host community,” explained the report.

Today, Samara has 40 registered hotels with 446 rooms for tourists and Nosara has 25 registered hotels with 259 rooms according to statistics from the Costa Rican Tourism Institute, (ICT). During the high tourist season, more than 200 people are employed in Samara hotels and about 250 people in Nosara work in hotels. The higher ratio of staff to rooms in Nosara reflects a larger number of high-end boutique style hotels. These figures do not represent the full picture, since many hotels and rentals don’t register with ICT. Still, taking into account that the total population is about 4900 in the district of Nosara and 3500 in Samara, the economic impact is substantial.

Regarding the economic and social situation in the canton of Nicoya, Jannelle Wilkins, the consultant who took the lead in gathering data for the report, pointed out that most studies show that despite the high amount of tourism in Guanacaste, the province has some of the greatest needs in the country and the highest levels of unemployment. In addition, many of the best paying and most skilled tourism-related jobs are going to foreigners or Costa Ricans from outside these communities.

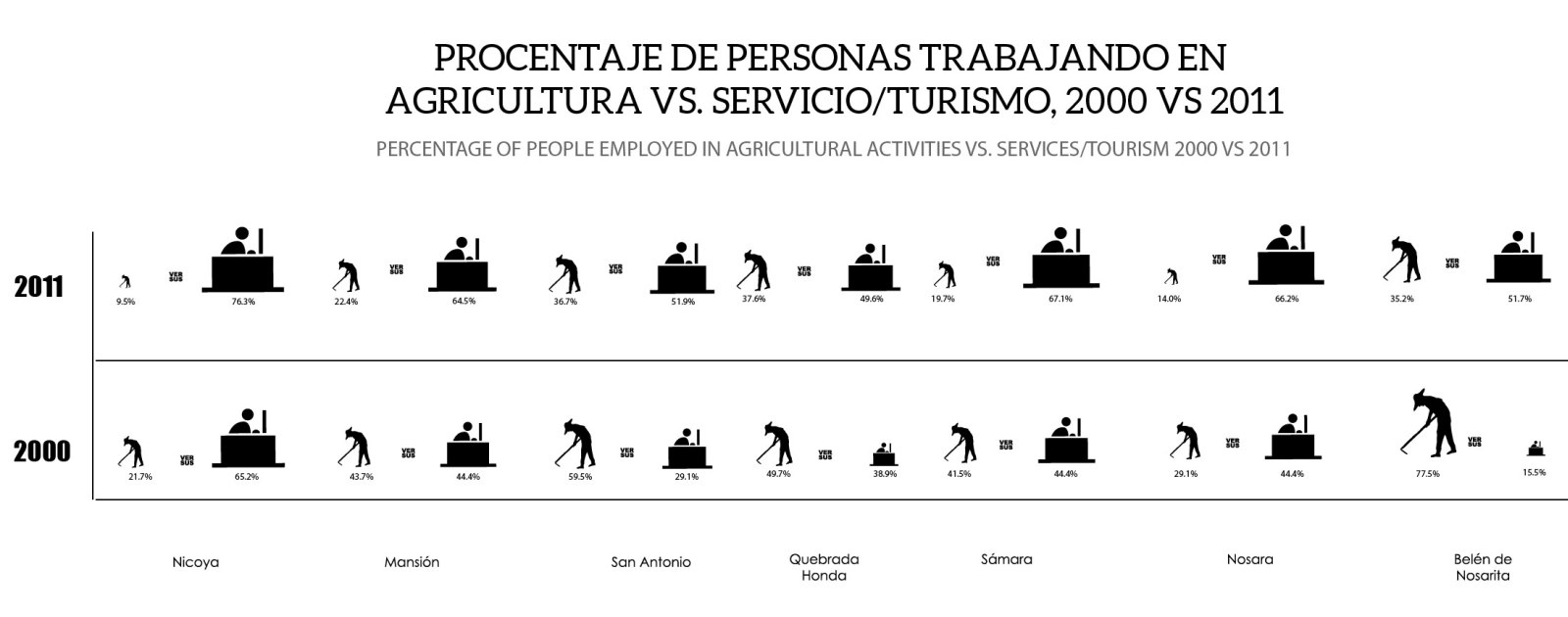

“Tourism is not the end all for the region,” she concluded, and explained that data shows that in districts that maintain a mixed economy of tourism and agriculture, poverty tends to be less and the lifestyle is better. However, if the economy shifts to be fully tourism based, or remains dependent solely on agriculture, poverty and unemployment seem to be higher. For example, in Nosarita de Belen, where more than 70% were still employed in agricultural fields in 2000, access to basic needs such as adequate shelter, a healthy lifestyle, access to knowledge, and other essential goods and services has remained below average to minimal.

Wilkins mentioned that the district of Samara has maintained more of a mix of agriculture than Nosara, which has become more tourism-dependent, although in Samara too agriculture is being displaced. According to 2011 census data, 19.7% of people in Samara are employed in the sector that includes agriculture, fishing and forestry, whereas in Nosara only 14% are employed in this sector.

This may be reflected in statistics that show slightly better levels of employment. In 2010, according to the 2010 Draft Zoning Plan (Plan Regulador), unemployment in Samara was just 3.5% while Nosara’s unemployment was 5.7%, both well below the national average, which hovered around 7.8% in 2012.

Data also shows some improvement in the last decade in the levels of poverty and the quantity of people lacking basic needs, although still high. Between 2001 and 2011, the percentage of households lacking at least one basic need improved from 62% to 34% in Nosara and from 66% to 48% in Samara, according to State of the Nation data. However, there is still room for improvement, as the national average is 24.6%.

Alvin Rosenbaum, president of the Nosara Civic Association and an international consultant specializing in strategic planning, sustainable tourism development, community organization and workforce development, in an open letter to the Playas de Nosara community, noted the need for job-specific skills and language training for locals so they can obtain local jobs that require these skills, rather than seeing these jobs go to workers from outside of the community. “As the economy changes from agriculture to tourism, the Tico community struggles with an antiquated educational system producing young people unqualified for the new economy,” he noted.

Martha Honey, co-director of CREST, specified that successful and sustainable tourism depends on many factors, and since some of these factors are beyond local control, such as global economic recessions or climate change, it is risky to become overly dependent on tourism.

“Keeping a mixed economy is better, assuming the other activities are profitable and sustainable. Local people often find it is more successful to be involved in auxiliary tourism projects – guiding, restaurants, handicrafts, agricultural produce, fish processing, and so on. This draws on their knowledge and expertise and takes less capital than, say, opening a hotel. In addition, it is good to be able to have a mix of domestic and foreign tourists. This can help to keep businesses going in low seasons or when the international economy is bad,” she explained.

Her recommendation is “to consciously strive to keep a diversification of economic activities, and not be overly dependent on tourism.”

This is part of a series of articles based on the investigative report by the Center for Responsible Travel (CREST), “A Portrait of Economic Realities in Nosara and Samara: Providing Tools for Sustainable Development.”

Comments