Juan Jose Alvarado still remembers what the coral reefs looked like in Playas del Coco, in the canton of Carrillo, when he began diving about 20 years ago.

They were the best, even better than those of Cocos Island. The diversity was very high,” said Alvarado, a biologist and researcher at the Center for Marine Research (Cimar) of the University of Costa Rica (UCR).

He recalls that they were all sorts of colors, sizes and types. “They were” because the reefs are no longer the same as they were two decades ago. In the late 1990s, 70% of reefs in Culebra Bay (which is in the cantons of Carrillo and Liberia) had live coral. Now the coverage is only 3%.

It is not a unique story. “So far it has been confirmed that at least one fifth of the world’s coral reefs have been lost, with some estimates indicating up to 50% loss of live coral,” according to one United Nations publication. In light of the global and national panorama, the Costa Rican government signed a decree in June 2019 to count, protect and restore them.

Two groups in Guanacaste have coral gardening projects to restore them. The Corals Project and the National Learning Institute (INA) began working two and a half years ago to repopulate the coral reefs of Samara. Another group started doing it in August 2019 from Matapalo (in the canton of Carrillo) to Culebra Bay (in Liberia).

The latter group has participation from experts from Cimar, the Tempisque Conservation Area (ACT), the German Development Cooperation Agency and the Papagayo Peninsula company, which provides boats and personnel to clean the corals. Members of both groups affirm that more fish will come to the area with the restoration of coral reefs, which will benefit fishermen and tourism because there will be more marine biodiversity.

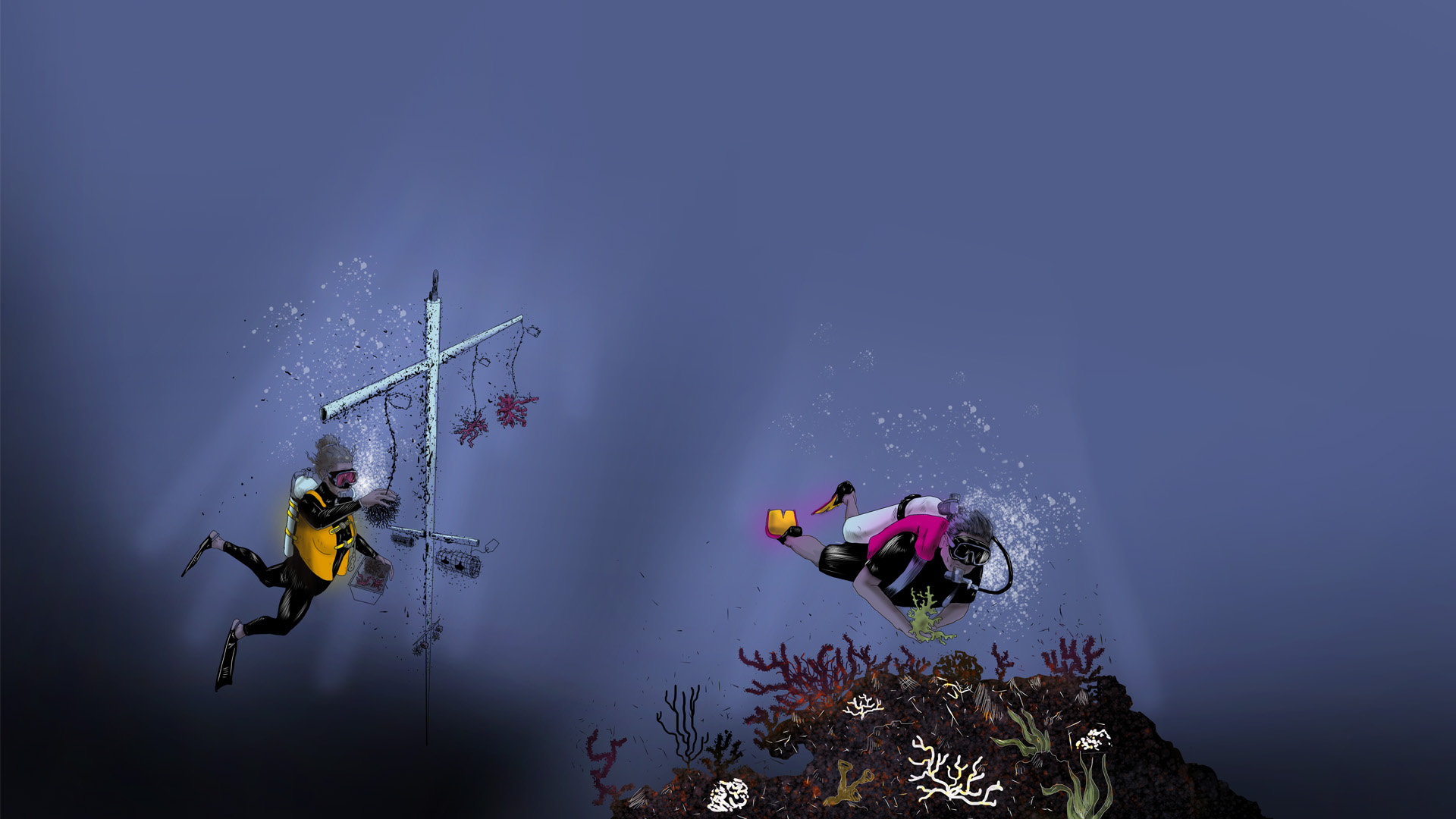

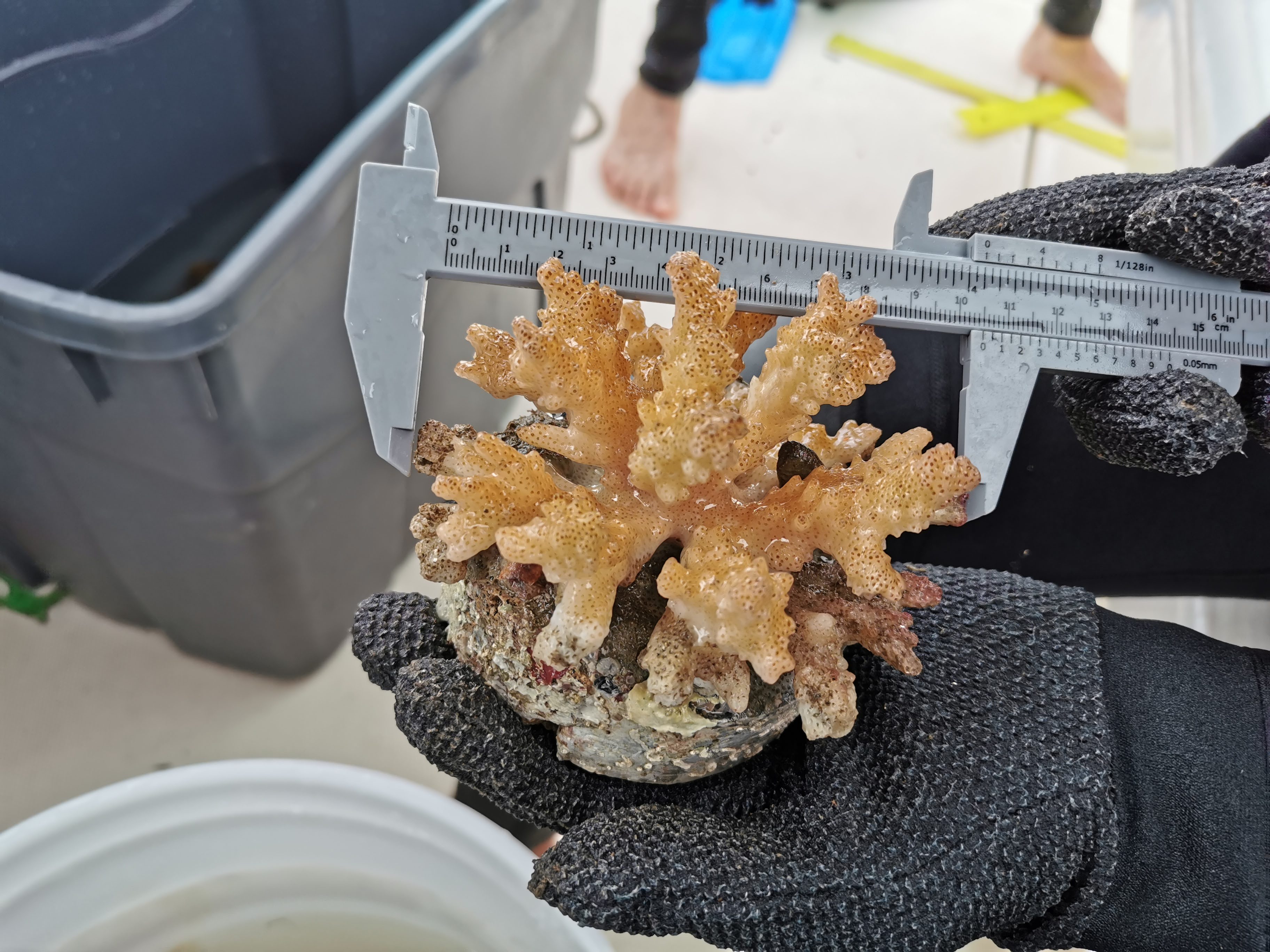

The gardening technique involves placing small coral fragments under the sea on a frame, which is a kind of vertical antenna or a horizontal mesh. When they are bigger, they are transplanted to natural reefs.

It is a method that began to be implemented for the first time in the country in 2016 in the Dulce Gulf, but it has been developed since 2000 in other parts of the world. But how did we get to the point of needing the intervention of scientists and communities to recover them?

Teams move coral fragments to artificial structures. After a few months, they move them back to natural reefs. Illustration: Roberto Cruz

Between Sea and Land

Corals are marine animals of different shapes and sizes located on reefs that are close to the coast. They occupy less than 1% of the world surface but are inhabited by 25% of marine species, such as mollusks, fish and sponges.

Since they are the junction point between land and sea, human and natural activities can damage them. For centuries, they had survived all kinds of climatic events, until the world development of the last 50 years began to accelerate their disappearance.

In fact, climate change is one of the leading causes of coral death.

The ocean has the ability to absorb carbon dioxide (for example from industries or vehicles), but it loses that capacity when emissions are very high. That acidifies the ocean and causes the temperature of both the earth and the ocean to rise.

Corals have a microalgae attached that gives them the necessary nutrients to survive but with acidification and temperature increase, the microalgae detaches and the corals die or “bleach.”

That’s why they seek to live in shallow waters, where there is light, good quality water and few sediments,” explained Alvarado. “So if any of these things alter, then corals stop growing.”

The increasingly frequent red tides also damage them. The phenomenon occurs when pollutants reach the sea, such as sewage from industries or sediments from agricultural plantations, as well as land excavations that occur during construction near the sea, Alvarado explains.

Algae from red tides make it difficult for light to reach the microalgae to feed corals, according to the Interamerican Association for Environmental Defense (AIDA).

Alvarado has studied the reefs of Culebra Bay for more than two decades and says that the deterioration began between 2003 and 2004, precisely when red tides arrived. Afterward, for reasons unknown to researchers, there was an overpopulation of algae that prevented light from getting to the corals.

What finished reducing the live coral coverage was the arrival of sea urchins in the area that began to eat the algae and, because of their food supply, ended up destroying the corals.

In Samara, on the other hand, there is no monitoring to determine how the loss happened.

I suspect that it deteriorated due to sedimentation, because at one time there was a lot of tourism development,” said ACT director Mauricio Melendez. The Corals Project researchers agree with him.

According to the monitoring they have done on this part of the Nicoyan coast, the most damaged reefs are near the Malanoche basin (between Samara and Puerto Carrillo of Hojancha). Martin Richard Paradis, from the Corals Project, says that there are more than 300 hectares (740 acres) of teak in the area. Teak leaves are so large that when rain falls, water and sediments do not seep into the subsoil but rather go out to sea. Corals are so fragile that any type of intervention affects them.

Este es un arrecife

In and Out of the Water

Predictions for corals are not very favorable if countries do not start taking restoration actions. “There are scenarios in which the coral reefs we know today are going to disappear completely by 2040-2050,” commented Alvarado. That’s why Richard and others in the tourism and fishing industries have been involved in the project in Samara.

Community involvement is a determining factor for its success. “We can’t [revive the corals] if things don’t change out of the water,” Richard says.

Alvarado and Richard agree that fishermen need to implement responsible practices, and hotels and companies need to be watchful so that solid and liquid wastes do not go into the ocean. They also insist that local governments need to control urban development.

On Cousin Island, in the Indian Ocean, for example, coverage went from 2% to 16% in two years with a project similar to this one, which combines coral gardening with actions to mitigate the impact that activities have on the coasts.

I don’t think that we will recover them 100%,” Alvarado stated. But then he emphasized that with good water treatment, tourism planning and land use zoning, corals could adapt to the impacts of climate change because “the stress factors are reduced.”

With that same vision, the Samara group has developed projects with the community, such as talks about caring for natural resources, tree planting days (to help with water infiltration and carbon dioxide absorption) and placement of structures that indicate places where boats should not drop anchors. In Culebra Bay, the team is just planning those actions.

Comments